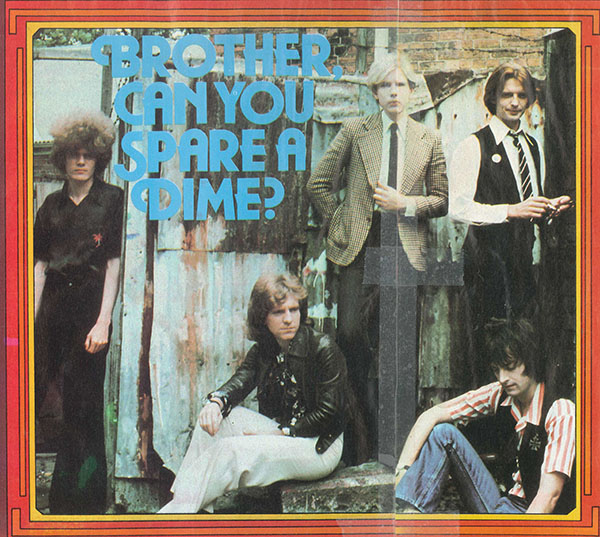

Young Modern: All dressed up with somewhere to go. Sydney.

Young Modern: All dressed up with somewhere to go. Sydney.

The journey began way back in Adelaide in the late 1960s when the teenage Dowler escaped the cultural claustrophobia of the City of Churches for London. Dowler spent two-and-a-half years living in London, working for a time in a record store where he managed to get his hands on records by bands like the MC5 and, later on, The Flamin’ Groovies, both of whom remained largely unknown back in Australia.

“I was obsessed with music, as were my friends, and that was all we talked about,” Dowler says.

After heading across to the continent for a year-long stint living and working in Amsterdam, Dowler returned to Australia in late 1973 where he formed Spare Change.

“I actually met the two main other guys who ended up in Spare Change in London, and we came up with the idea of the band there, we’d sit around with acoustic guitars, doing stuff, and we headed back about the same time, and had a band together by early 1974.”

Hearing Big Star’s "Radio City" album was a “life changing experience,” Dowler says, and further honed his musical interests. Dowler subsequently took Spare Change across to Melbourne, scrounging out a subsistence musical existence, as well as sharing a house for a time with a skinny fellow Adelaide expatriate by the name of Paul Kelly.

When Spare Change broke up, Dowler returned once again to Adelaide where he formed Young Modern. From around 1977 to late 1978, Young Modern was the hottest local band going around in Adelaide, regularly selling out the Tivoli Hotel in Pirie Street. But a move to Sydney to try and ratchet up the band’s national profile proved ill-fated and by mid 1979 Young Modern was no more.

Dowler was so unimpressed with the Sydney scene that he was moved to write "Don’t Go to Sydney", which became an independent hit when The Zimmermen released it in 1985.

“Going to Sydney was like going to a foreign country,” Dowler muses. “Young Modern were much more popular in Melbourne than they were in Sydney, even though we were living in Sydney. I lived in Sydney for a year, and we made a few friends there, but none of them were from Sydney, they were all people who’d come from interstate. I always found Sydney very alienating”.

Counter-intuitively, Dowler left Sydney just as the city – in particular, the inner suburbs of Surry Hills and Darlinghurst – became the epicentre of the Australian independent music scene.

“It’s the story of my life, always being in the wrong place at the wrong time, always picking the wrong option,” Dowler laughs. “I was a lot more comfortable in Melbourne. I didn’t want to go back to Adelaide because I found it very small. And I’d really enjoyed living in Melbourne, with that circuit around the Kingston, Heart’s and Martini’s”.

Back in Melbourne Dowler was invited to audition in The Marching Girls, recently relocated from Auckland and transformed from its scrappy punk origins as The Scavengers.

“It might have been Des [Hefner] who approached me,” Dowler says. “They’d just lost their bass player, and they needed a singer. We had maybe five or six rehearsals. We were doing five or six of their songs, and four or five of mine, but it just petered out. I got along pretty well with them, even the guitarist, John [Cooke], who had a bit of a reputation, but I always found him pretty nice.”

Soon after Dowler formed The Zimmermen, with former Cuban Heels guitarist Steve Connolly on guitar. Later both Connolly and Zimmermen drummer Michael Barclay would be poached by Dowler’s fellow Adelaide expatriate and one-time housemate Paul Kelly.

“I was really disappointed when they left, and annoyed at the time, even though we remained friends at the time,” Dowler says. “We were doing some recording and it was sounding pretty good, so it was pretty frustrating.

"As it happened, when we doing some recording later on, Paul Kelly and the Coloured Girls were in town at the time, so Steve played lead guitar on ‘Don’t Go to Sydney’ and Michael did harmonies. But good things happen, and we ended up getting Peter Tulloch who was a great guitarist and songwriter.”

Both Young Modern and The Zimmermen were on the cusp of bigger things, only to be cruelled by the fickle hand of rock’n’roll success. Dowler isn’t bitter at the way the chips fell, although he does admit he could have “drunk less”, and possibly been “a little less lazy”.

“I was also very uncompromising,” Dowler says.

Dowler flitted between various projects over the next few decades, before forming John Dowler’s Vanity Project in 2014, with Mark McCartney and Justin Bowd on guitar, and the rhythm section of Stephen O’Prey and sometime Kim Salmon drummer Mike Stranges. Dowler is the titular leader of the band, but it’s a group effort.

“Everyone joined the band knowing what I liked,” Dowler says. “The only reason it’s called John Dowler’s Vanity Project is that Mark thought, mistakenly in my opinion, that that might give us a leg up in terms of being well known,” Dowler says.

Dowler is the musician of whom it's been said “rightfully owns the Melbourne hard jangle”. His new new album, "12 Stitches" is a harder album than the group’s 2016 release, "Splendid Isolation" (a title which, in hindsight, seems disturbingly prophetic).

“Everyone has autonomy to play how they want, and there are three songwriters in the band, so it’s a proper group.”

"12 Stitches" includes a tribute of sorts to Dowler’s drummer, Mike Stranges, an up-tempo glam-power pop track called "Stranges in the Night".

“We were thinking of doing an album, but we didn’t have enough songs. Mike had been threatening to go to Europe for a while, and then he bought himself a ticket. Mike had some bits and pieces of songs, and I got him to send them to me, and we wrote a whole bunch of songs, and ‘Stranges in the Night’, well, we weren’t sure if he was coming back, so we called it that.

"I thought he’d be too embarrassed to call it that, but he did, so there it is!”

In the midst of other modern day power pop gems, Dowler has taken the opportunity to re-record of couple of his older compositions, Spare Change’s "Let’s Get Rich Together" and The Zimmermen’s "Ordinary Man", as well as covers of Brian Wilson’s "That’s Not Me" and a Phil Judd composition "Time for a Change", from the first Split Enz album.

“I first heard that song when it first came out, and they came to Adelaide when the album first came out, they played the Arkaba, and we couldn’t believe how good they were,” Dowler says.

“I’ve always loved that song, it always rang a bell with me. I have a manilla folder of songs that I’ve always loved, and I dragged a couple of them out for the last Vanity Project album, and two more for this one.”

Dowler keeps his ear to the ground for new music, though he acknowledges that he’s more inclined to listen to “new music that sounds like old music”.

“They’re usually guitar bands, so maybe I’m not as adventurous as I like to think,” Dowler says. “It all comes down to the songs. There’s a million bands that sound like Big Star, REM or The Byrds, but most of the songs are really weak.”

With all of the members juggling domestic and other musical commitments, Dowler’s Vanity Project is a sporadic presence on the Melbourne music scene. And when it does make a live appearance, it’s hard to be heard over the noise of other (usually younger) bands clambering for attention (Dowler makes a dry observation about his band "practising social distancing long before it was fashionable".)

“Being in a band is one of the very things that I’m good at,” Dowler says. “I get an enormous amount of satisfaction out of writing songs and people playing it, so I write to please myself, but you always like to get the acclamation of your peers – even though I have precious few of those peers left!”

"12 Stitches" is out now on Half a Cow Records. Buy it here.

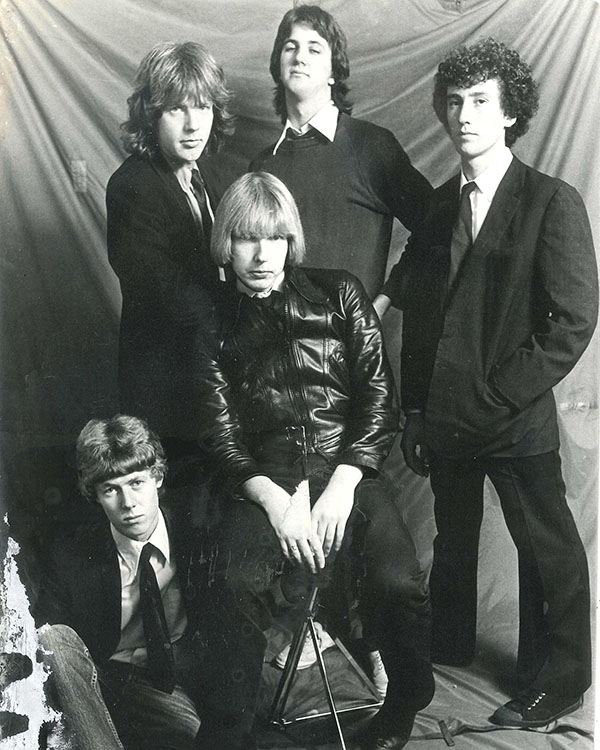

John Dowler (second from he left) and his Vanity Project.

John Dowler (second from he left) and his Vanity Project.