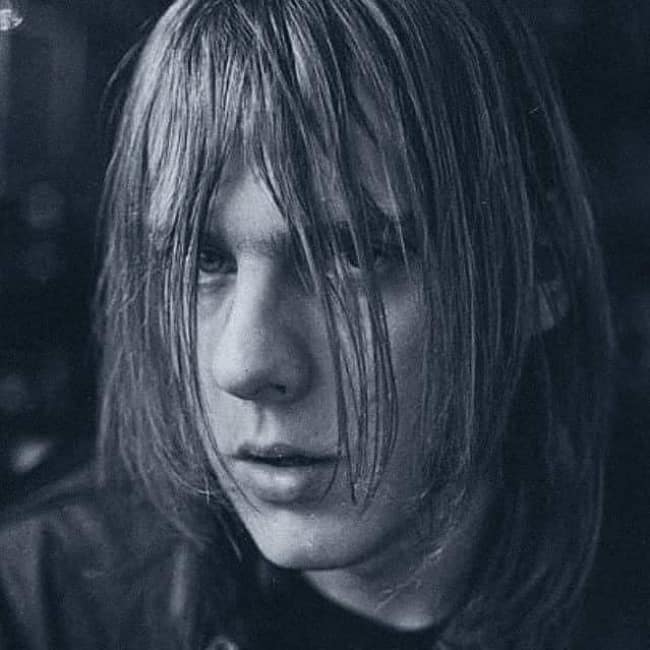

So I got it from my brother, and at the tender age of 12-years-old I was already playing weddings, and by 14 I was playing clubs with my brother.

So anyway, in high school and junior high school, I met the other guys and we had a band. The band was called the Bounty Hunters, for Steve McQueen back in those days. Wayne (Kramer) played in the Bounty Hunters for a real short time. Wayne taught Fred (Smith) how to play guitar... Fred would go over to Wayne's house and Wayne would show him how to play chords, and that's how that happened. Fred became actually the better rhythm guitar player, by his natural, innate ability.

So I'm in high school, and this is about, we're talking maybe eleventh grade, maybe tenth grade, they formed the MC5, which was Wayne Kramer, Fred Smith, Rob Tyner, Bob Gaspar on drums, who has passed away, and Pat Burrows on bass. They were in the band for maybe six months, and they aced out and did the Dave Clark Five show at the Ford Auditorium in downtown Detroit.

Well, they started moving into this avant-rock business, where they bought more amps and started getting louder and louder, and Bob Gaspar the drummer was bitching, he says, you know, "I gotta keep slamming these drums so hard, I don't wanna play this way." And Pat Burrows the bass player was gettin' pissed off, and said, "I don't wanna do this crazy stuff." (He was from the James Jamerson school of Motown bass playing). So these guys got disaffected.

So one day Wayne pulls up on his motorcycle at my house, and I'm still in 10th grade, so that's makin' me 15, 16? Somewhere around there...pulls up and says, "Hey, do you wanna play this job we got? Our drummer quit. It's a place called the Crystal Bar." And what it is, is a shot and a beer joint -- it's a dump.

They had flyers made up and everything...the name of the band's the Motor City Five. "Okay, I'll do the job." He shows up on his motorcycle in the middle of the night and [I] went down and did the job for the weekend. We had about three toothless bums just sittin' there. And here we are onstage playing "My Generation" and Yardbirds and Kinks and all. That's when I joined the Five.

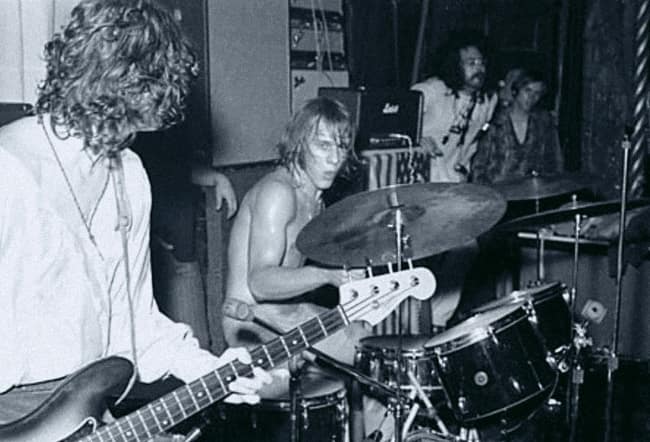

With Michael Davis in the MC5. John Sinclair at right.

With Michael Davis in the MC5. John Sinclair at right.

K: Was "Black to Comm" in existence back then?

D: No, that happened at the Grande Ballroom...you know what "Black To Comm" means?

K: No, I never understood that.

D: Okay. "Black To Comm" was when we were playing the Grande Ballroom, we used to let bands -- a lot of bands would use our equipment, and we would say, "Fuck you, if you break it, we told ya...'black to Comm.'" Quite simply, on the P.A. amp, "Comm" is commonly referred to as the negative ground, and the "Black" was the wire...clear from the power source, right?

And that's exactly what it was, it's like, "Okay, just be sure you put the black wire into the comm connection here," you know what I mean? "If we trip over it and knock it out again" -- because there was all these wires strewn across the stage.

This is back when technology was...there was no technology. It was low technology. And we were one of the loudest bands on the planet. Us and Blue Cheer, I believe, would probably be the loudest..."the firstest and the loudest." And we'd do it on purpose, because going to a Catholic high school like Aquinas with four Marshall stacks, totalling eight Marshall stacks for guitar players and two Sunn cabinets for the bass player, and going into a gymnasium for basketball, and just watching the nuns, the top of their habits they wear...watching it blow off, was worth it. And the kids, you know what the kids were doing, they were dancing and prancing and having a blast.

So we just used that title, that became the title of this riff, this riff was just, well, Fred would just start out [sings the two chord intro to "Black to Comm"] and we never knew where the song would go; this was our free-form forum just to experiment. And Rob wrote just a few lyrics for it at the beginning and it was real exciting, and of course, that's what caused Burrows and Gaspar to quit the band, because they started getting into this "avant-rock," which is what we called it; the Yardbirds used to call it "rave-up" -- that's when they started really playing and going crazy.

So, eventually that evolved, and the more that we got involved in John Sinclair's jazz influence, we started listening to Ornette Coleman and Archie Shepp and Pharaoh Sanders and John Coltrane -- especially John Coltrane -- and John Sinclair had this record collection that was one whole wall, you know what I mean? So we started listening to all this great music and it started to affect how we played. Then we started getting into just plain sound explorations and feedback and just working with sound. You add a little LSD to that and it gets pretty crazy.

K: As far as your own drum style goes, you've always talked about Elvin Jones, and you can hear a lot of that on "Ice Pick Slim" on Alive -- there's definitely a lot of Elvin there.

D: That's an Elvin groove.

K: And on Thunder Express there's this version of "Rama Lama Fa Fa Fa" that's like the bridge between the JBs and Funhouse...a lot of funk in there. Who were some of your influences on the traps?

D: OK, my major influences, in no particular order, would be Keith Moon, Mitch Mitchell from the Jimi Hendrix Experience, John Bonham.

K: Really?

D: Mmm-hmm. He had some pretty fat, snappy grooves, and he had a big drum set. We played with Led Zeppelin maybe eight or nine times and I'd watch him, y'know, "This guy's definitely got his chops together;" he was doing all that bass drum triplet shit before anybody was doing it. And doing it hard.

So he was an influence inasmuch as I picked up a few tricks from him. I liked Charlie Watts in the Rolling Stones; I liked Stax/Volt -- I don't know who that session drummer was, but I liked the Stax/Volt session drummer.

K: Al Jackson or somebody like that.

D: Wilson Pickett and all those; I loved the Motown drummers, of which there was a stable of 'em. Billy Bruford from King Crimson; I'm thinking about what influenced me -- now I'm my own guy. There's so much electronic drums now that I don't wanna get into that part of it. The Yardbirds' drummer too, and the Kinks'. The really good early English bands: the Animals, the Hollies.

K: The Pretty Things?

D: For sure, Viv Prince...The Byrds. Even Joe Butler from the Lovin' Spoonful; I saw him when I was 16 at the State Fairgrounds here in Detroit, and he was slappin' 'em hard, and I didn't realize, "Wow, the Lovin' Spoonful; here's Joe Butler and he's playing matched grip and he's smacking 'em".

And the reason a lot of us young drummers had to hit 'em so hard then: 'cause we weren't miked. The only way you could cut through the Marshall stacks, or the Sunn stacks, or the Vox stacks of the guitar/bass setups was to hit 'em as hard as you could. Because we really didn't have the technology up to speed; in most places, unless you had your own P.A. system and you had a 16-channel board, which we didn't have, you couldn't mike the drums up, so you had to develop a style that was really pretty powerful. 'Till eventually, down the road, we finally started to get miked, and then you could develop more of an Elvin Jones style, where there's a little more wrist involved.

But what I did, I studied Elvin Jones and Rashied Ali and Billy Cobham. There you go. There's a list that is probably the coolest drummers you could...oh, excuse me, gotta get serious...Buddy Rich and Gene Krupa. That does it. I can't forget Buddy. That was when [drumming] was all about the wrists. And then what happened was, probably because of rock and roll, you had to pretty much scrap the wrists and get into the arm. Now you can do whatever you want, so it doesn't matter.

Promoter and DJ "Uncle" Russ Gibb.

Promoter and DJ "Uncle" Russ Gibb.

K: Talk a little bit about Russ Gibb and the Grande Ballroom.

D: Russ taught in the Dearborn school system, English and history I believe, and he was a part-time disc jockey. There was a workshop called the Artists' Workshop on the Wayne State campus. (I went to Wayne State University for two years and I studied physics and engineering.)

The Artists' Workshop was right below us; we lived in a dentist's office, an old dentist's office right above it. And on weekends they'd have poetry readings and jazz bands, and Wayne and Rob met John Sinclair, and the first time we played one of those sessions was on a Saturday or Sunday, and there were three or four jazz bands, some poetry, then the MC5 came up and just blew the place. Leni Sinclair [John's then-wife] pulled the plug on us; she said, "You're too fuckin' loud."

Anyway, that night, Russ Gibb showed up. Either Rob or John (I'm a little foggy here)...Russ had contacted them, that he wanted to start a ballroom similar to the Fillmore on the West Coast, he could see that there was a market for that type of thing. He didn't own the Grande but he leased it from an old fella [Gabe Glantz] who owned the building. Russ said, "Would you guys be interested in being the house band? I can't pay you nothin'." We needed a place to play, a large place to play, and a place to rehearse...[so we said] "Oh, yeah, this sounds like a great idea, 'cause we're starting to get all the feedback from the Avalon, the Straight Theater, and the Fillmore.

So that's pretty much how it started off. We probably played there six-eight months without making a dime. We were just happy to be the house band. When we first started playing the Grande, we rehearsed there in the afternoon with our coats on, because there was no heat, and we played for free. We were just in the spirit of what was happening in California. The bottom line is, we stuck it out and we played for free and we developed a following.

So Russ was instrumental in organizing the scene, the focal point being the Grande Ballroom. But at that point in time there were a lot of places you could play around town, little clubs, sock hops, high school dances, sweetheart dances, roller rinks, battles of the bands, not to mention your colleges and junior colleges.

There was enough of a scene that a band could make just enough money to basically survive, and the Grande was the gig you wanted to have. In the beginning, there were no national acts, you just had the locals, but you've got Bob Seger playing, you've got the Rationals playing, you've got Ted Nugent and the Amboy Dukes playing, the MC5, the Psychedelic Stooges, Third Power, Savage Grace, and these local bands all had followings.

And what was happening was all these followings were merging and the camps were coming together like tribes and we're starting to get a decent crowd. Decent enough to where Russ Gibb could actually start bringing in national bands. And once the national bands came in, the Grande became a pit stop. So Russ' influence basically runs pretty deep. He ran the business of it; eventually, we started to get paid, and I believe he's still teaching school.

K: Really? I'll be damned.

D: Mmm-hmm. It's just that he's older; he wasn't a crazy person, he wasn't unstoppable like we were, I think was, if anything, just a little pot smoking, but he wasn't into the LSD or anything else.

Leni Sinclair photo.

K: What were your best and worst memories of being in the Five?

D: Best memory? I dunno, I'd have to call it the [1967 Detroit] Belle Isle Love-In...really the best show. That's when we were perfectly in tune. Worst memory? The band breaking up. That was in...'72. At the Grande Ballroom.

K: Give us some impressions of Rob and Fred. Something you remember that kinda captures the kind of people they were.

D: Mmm. That's a tough one. Rob, I'd have to say, pretty much the intellectual part of the MC5 body. The philosopher, the, how would you call it, the inner space probe artist...(Long pause) Rob the poet, Rob the philosopher, Rob the thinker.

Fred Smith the rhythm guitar player, the creative musical person in the band, the most musically driven. Fred was the rhythm guitar player and he'd come up...like Brian Jones in the Rolling Stones, he would come up with the coolest guitar parts, and Wayne Kramer was more or less the icing on the cake. He was like the showman de rigeur. He was the person you'd put up front to do the dancing, the swinging, and the twirling, and the swirling, you know what I mean? The Peter Townshend focus. Wayne was better than Peter, 'cause he could dance.

And then you got Michael Davis who just more or less was the bottom line, the bass player, and his role was just to play the bass, but when we all started to do our crazy movements, Michael was into choreography, because we used to rehearse this shit.

That's how cool we were (Laughs) -- rehearsing breaking up your equipment. John Sinclair used to get so pissed off because he was trying to juggle our bucks, right? The money we were making? And we were breaking shit up faster than we could buy it. That was the biggest complaint. "You gotta stop doing this auto-destructive shit." We said, "John, take a look at the fuckin' response from the audience." We did it creatively.

You know, Peter Townshend started it by smashing his guitar and running it backwards into his amps. But we used to destroy the whole fuckin' stage. We're talking about doing this in 1967. (Laughs) Pretty cool.

K: Talk about the Stooges a little bit. It seems like over the years you've had a lot of association with those guys in different ways.

D: Off and on, with Ron [Asheton] especially. We were together, I would say '71 to '74-'75, about three or four years in California in a band called the New Order. That was Ron Asheton on guitar, myself, Jimmy Recca -- who was in one of the latter day versions of the Stooges -- played bass for 'em, a guitar player from Detroit, Ray Gunn, and David Gilbert who became the lead singer of the Rockets.

Live with New Order.

Ron and I like to do projects together occasionally, and he's pretty busy. Doing a lot of work; the Stooges are really visible. In the beginning, we considered them...apprentices, but they were friends of mine, Mike Davis and the road manager, Steve Harnadek (we called him "The Hawk"). We would go hang out at the Funhouse, which is right in Ann Arbor. And these guys were just learning how to play. When Scott Asheton first played drums, he had two old 50-gallon oil drums. Very, very slick, hahaha.

K: So that's a true story!

D: Yeah! They were really like the first true performance art band. They couldn't play very well, so they played all this simple stuff; real simple riffs and rhythms. Ig would have to just overreact, overrespond, overdramatize to get the band to get over when they started playing the circuit. That might be what caused him to develop his singular style. And those guys played together, and they got better and better.

We always referred to them as our brother band; when we got signed, Danny Fields came out here from Elektra Records, he was the head of the A&R department, Jac Holzman was the president. Danny came out to sign us. He saw the Stooges and fell in love. So actually, Elektra got two bands for the price of one...we both got signed. The "pizza pizza" deal.

Well, what happened is, the day after we signed, we started to go our separate ways; they MC5 did their thing, [the Stooges] did theirs. They went through their trials and tribulations; Davey Alexander died, the bass player, but Ron was with them the whole time. So Ron and Scott [Asheton] are my real good friends. Iggy? I'm a friend of Iggy, but we don't get along all that much. But the guys in the MC5, Wayne specifically, and Fred, didn't think too much of those guys. Rob thought they were very, very cartoonish and liked them. He said they definitely had a future. Which proved to be a fact.

K: I'd like to talk a little about the MC5 recordings. On the Ice Pick Slim CD, there was a [Kick Out the Jams outtake] version of "Motor City is Burning" that was kickass, I thought it was better than the one Elektra released. Is there anymore stuff like that?

D: I'm sure there's one or two versions that are gonna be popping up at you yet, coming down the pike, 'cause I know a couple of people who are putting together some packages that are going to go out on a brand new independent label being created, so keep lookin' in music stores, 'cause there'll be more. There's a lot of stuff that was recorded.

A lot of it, the quality of the recordings is terrible, and I'm not just getting excited about a lot of shitty-sounding bootlegs, but there's some better stuff coming down the road. I happen to know the people who are involved, and they're gonna make sure that there'll be a sign-off. In other words, we'll be able to listen to it beforehand and give it our stamp of approval.

Most of the bootlegs you hear have never gotten the approval of the remaining members, including Becky [Tyner] or Patti [Smith]. They're just bootlegs. A lot of it's just off of shitty boomboxes, crappy four-tracks, and there's not much you can do to clean that up. It doesn't mean anything about the performances. That was a good period right there. That was when we were trying to become legitimate.

K: That definitely comes through. Some of these long tracks are like a rock version of 'Trane's "Meditations".

D: Yeah, there you go. Which for most people is too intense. I've had a lot of people, when I play them the 'Trane stuff, they tend to gravitate more towards the more "Broadway", the more lyrical, the classic tunes. Because when they hear "Impressions" and "Meditations", it scares the fuck out of people. They think, "These people are nuts!"

But I tell 'em, "Hey, you can still count the 6/8 in there, buddy. You can still count the 9/4, or the 5/4; it's still there." That's for us musicians to learn from. A guy like 'Trane to me, musically, is like Rembrandt is in the art world. He's a guy that just gave it all. There aren't many of those around.

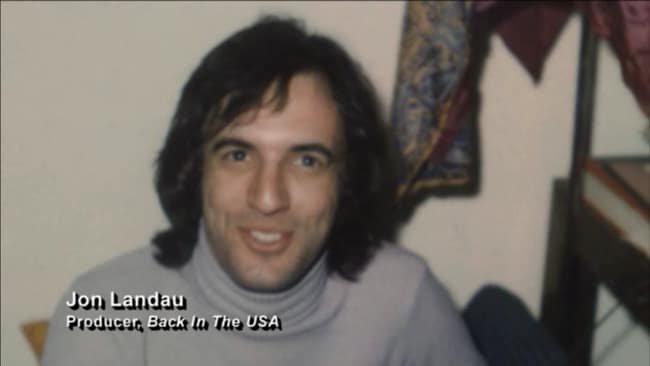

K: Talk about Back In the USA a little bit. I understand that before you guys got dropped by Elektra, you were cuttin' out in L.A. with [producer] Bruce Botnick. Is that true?

D: That's correct. Those tapes, right now, are trying to be located by a certain person that I know. By a couple of people, more than one or two people, actually. And we don't know whether they exist or not. The last I heard was that they do have them. These were cut in Los Angeles. It's most of the material, not quite, maybe three quarters of the material that was released on "Back In the USA", but done in the old MC5 way, before Jon Landau came and cleaned us up. Mr. Titanic man himself.

K: Talk about what is really one of my favorite records of all time, "High Time".

D: My favorite. It was the first record that we produced ourselves. We had a producer who was a "stable" producer for Atlantic, Geoff Haslam. He had an English background, so we recorded a couple of tunes in England. We were touring; at that point in time in our careers, we were spending a lot of time in Europe.

And we did, I believe, "Sister Anne" and...two tunes in Europe. But Geoff would sort of work with us and not tell us what to do, and let us sit behind the board and play with the dials and the mix, and let the whole group sort of work at it together, and then when it came down to a mix-down, we all would defer to Fred...let Fred and Wayne and Jeff do the mix. And finally we came up with a product that should have been released as our first one, 'cause that's pretty much how we played when the band started.

Hey, the story on our first record ["Kick Out the Jams"] is that we were told by Jac Holzman, the president of Elektra, when they came out to record us with a 24-track mobile, we were told that if we didn't like it, we could do it again. Well, after we heard it a few days later, we all said, to a man, "We wanna do this again." But we had a big poster made, and a big event made, "the MC5 recording," so Holzman sort of had us in the bag. He sorta figured out, "Well, if you do this again, you'll look like amateurs." We said, "Well, we'll do it in the studio." John Sinclair and Jac Holzman decided, "This is good stuff. This is capturing the MC5. We don't give a flying fuck if it's a little sloppy."

During the second album's period, we tightened up our playing, realized that y'know, we're not gonna get a second chance, because we were told we'd get a second chance [on the first album] and we learned from that mistake. So the second album, well, John Sinclair went to jail, excuse me, we had new management, the record company shitcanned us, we were stuck with an accountant as our manager (Danny Fields in the interim sort of managed us for a little bit), then they signed us to Atlantic Records and Jon Landau, as producer, was Jerry Wexler's favorite son. He'd already produced Livingston Taylor, his first project, and his second project was us.

His third project was to be J. Geils, but J. Geils and our band had become friends from playing Boston, we got to be buddies, and after they heard "Back In the USA", they went shopping for another producer to do their debut record, and the rest is history, as you know.

In this business, especially back in those days, no one wanted to touch us. The corporate state hated our guts because we were rallying against them. But you have to rely on them to get your product out. It's really a ridiculous twin paradox. It's like, "bite the hand that feeds you"...you gotta play ball with these people. And what they'll do is, they do have the upper hand, 'cause when we hit, we hit hard and fast and strong, but we didn't have our business acumen in order.

We had John Sinclair and the White Panther Party, and basically we were in conflict with his agenda. He wants to legalize marijuana and then have a revolution and get rid of all the pigs, y'know, and we really didn't buy that. We just wanted to be bigger than the Rolling Stones. We wanted to be just a big, big, big rock and roll band. You know, and just be players. And be stars. And get laid. And have fast cars.

We believed in politics, we believed in philosophy, but we didn't wanna teach, we didn't wanna make it like here we are out there preaching and banging a gong or being on top of a lectern saying, "Well, here's what you gotta think." That was all Sinclair's influence. More or less.

So it got mucky when he went to jail. Then we go to Atlantic, and we didn't have the leverage to say, "No, we don't like this Jon Landau guy," because he was picked by [Jerry] Wexler and Ahmet Ertegun, so we had to go with him. And the relationship...well, the guy's brilliant, but trust me, by the time we woke up, we'd bought ourselves a nice home in Hamburg, Michigan, and it was about ten acres. It was nice. And we had a big huge practice room, and things were going pretty well there.

But here's Jon Landau, who's an intellectual, right? He's your typical brilliant liberal intellectual, used to be a journalist for the Rolling Stone, etc., etc., good writer, [and] he loved R&B, he loved rhythm and blues, he loved Motown, he loved rock and roll. But he'd never produced anything before.

So it's great that you love music, and that you can actually figure out the New York Times crossword puzzle before we even wake up in the morning, that's pretty cool; but when we get to the studio, he doesn't know nuthin' -- he's got a tin ear. So that album came out balls-less, thin sounding and sterile and too fast. Basically from our response to Landau, and his lack of experience at that time -- that's why that music came out that way. Now if you look back in retrospect, 20 years later, you say, "This stuff's not bad, it's a cool record," but it's a cool record that doesn't have the MC5's fuckin' punch to it.

K: You compare that version of "Looking At You" to the single version and it's like night and day.

D: Oh, yeah. It's a 180. Well, that's how much a producer can affect a group. Seriously. He wouldn't let Mike Davis play on one of the songs, the bass player, unless he could learn his part perfectly. We had to do 36 takes on "Tutti Frutti" because he dropped one fuckin' note. So you're talking about essentially an excellent journalist, who is now in the driver's seat to produce the hottest band in America. And boy, what a clash of the titans.

So if you take that bit of information and tie it into "High Time", you can see that what we did on the first album was a little bit too...it's like under-compensation and over-compensation. The first album was a little bit too rebellious, a little too pirate-shippy, a little bit too much rum and grog and acid; the second album, all of a sudden these guys became priests and nuns, right? Or we joined the Webelos or the Boy Scouts. Then the third album we sorta got a nice blend of who we really were -- creative, strong, and tight.

K: The playing on that is so great and the songs still stand up really well.

D: Yeah. A lot of the songs were written by Fred. Bless him. And at that particular point in time, we were playing really solid. So, finally, the reason "High Time" came out as a good record...I think we gained experience, we gained studio experience, and we learned to steer away from certain situations. It was a maturation process.

But by that time, we'd alienated two different factions of our audience, the industry didn't like us, the kids didn't know what to think about these guys, but Europe appreciated us, so we stayed in Europe. But then we were having other problems.

There was just nothing but constant harassment because of the obscenity, because of what we stood for. So we were always gettin' harassed, everyplace, by the police; it drove guys into situations where we did too many drugs. Had we been able to maintain stability, emotionally, spiritually, and mentally, we would still have been a band together today. But the times...I can't describe to you, it's like five people and take them from a normal life and then throw them in the middle of a fucking hurricane. And if you survive it, God bless you.

You ever heard the "Gold" stuff, off the "Gold" album?

K: Just that one track that was on "Babes In Arms".

D: There's another one that's a little bit hipper than that. That's on the "Gold" soundtrack; you probably can't get that here, I doubt it's even in CD form. I don't even know how to get it myself. I still have the album, but I don't even have a turntable anymore.

K: One more question about "High Time". Talk a little bit about the division of labor between Wayne and Fred on guitars, 'cause Fred was always ostensibly the rhythm guitarist, but I understand you actually wrote "Gotta Keep Moving" to showcase his ability to play 16th notes.

D: Thirty-second notes. I wrote that 'cause Fred could play it really well, but see, Wayne was the flash, he would do most of the solos, and Fred held down the rhythm chords. 'Cause Fred was incredible in terms of rhythm and having an original feel to rhythm guitar playing. But he could also play lead like a badass sonofabitch. So I just made up my mind, "I'm gonna write a venue for Fred to show off his 32nd note dexterity."

K: So that's actually him on the record then doing all that hairy stuff?

D: The first stuff you hear, you're gonna hear swapping back and forth, you're gonna hear...when you hear that one particular guitar sound, that's Fred, you can tell it's Fred. Fred will take off into Thirty-Second Note Land and play through all these breaks -- that's what I wanted to do, 'cause that's how good he was -- then Wayne would take the next break and do the same thing, right?

I got together with Fred after I got an idea for it -- "Hey Fred, we're gonna do a real fast fuckin' song, and I want you to play that thirty-second note thing that you got down so pretty" -- 'cause him and I used to be pretty good friends. And we worked on it and put it together and then Wayne, when we started doing it live, first, Wayne said, "I'm not gonna let that fucker show me up." So that's exactly what I wanted, was a battle of the two guitar players, and it turned out pretty damn fine.

Fred was a player, and before he died, Fred was getting to be a really good guitar player, and he was really moving into a spiritual kind of place. Fred and I also had a band together and here's a great, great story that no one knows. After the MC5 broke up, about six months later, I was living in Detroit. Fred and Michael and myself got back together again, and we rehearsed in my attic in an old-fashioned two-story brick house, the old well-built ones. The attic was like a 125 degrees. Well, that's where we rehearsed, 'cause I lived in the upper fucking flat. Well, we put out the word to Rob, "Would you like to join our band?" And Rob declined. And we put the word out to Wayne, and Wayne declined.

So Michael, myself, and Fred found a bass player named John Hefti, and we had a band called Ascension, and we probably played like two or three shows. Now there's another little CD that'll be coming out, 'cause this music here is really out there, it's really good stuff. It's Fred playing the best Fred, and me doing my little jazz stuff, and a real good, solid bass player, and Michael was doing the vocals. You're gonna hear a whole new version of the "MC3" that no one's ever heard.

But we did make an attempt to put the band back together again. And the three of us were up there sweatin' our balls off in the middle of 120 degrees because we all wanted to do it again. Everyone was free and clear of all drugs, all alcohol, nothing, we were completely ready to go again, okay? Rehab City, let's go. And they declined, so it never happened. So that's a story not too many people are hip to.

K: I'm still really confused about the chronology, 'cause the date you always hear for the breakup is New Year's Eve '72 at the Grande, but didn't you guys do a tour over in England in March of '72?

D: Yeah, they did a tour as the MC5, but not with me, not with Rob and not with Michael. Fred and Wayne went over as the MC2 and hired all pickup musicians in Europe. And they fell flat on their fuckin' face. They did three or four dates and they were back.

K: After the Dodge Main show in Cleveland when Jimmy Zero from the Dead Boys got up and played with you, he did an interview with one of the magazines there [Scene] where he compared the experience of musicians from your era with that of the Vietnam veterans. Would you care to comment on that?

D: What did he mean?

K: He said, "We do have a lot in common with Vietnam veterans. Not to demean or play down what they went through or to compare our experiences to theirs, but we went through some things together and turned into comrades. We survived that thing, and some people didn't survive that we were all friends with. So there's a spirit that will last the rest of our lives that people who are investigating it or are curious about it or ar fans of it will never quite get that same spirit."

D: Okay, I understand. Well, yeah. Our Vietnam was here. Our brothers, cousins, best friends went to this crazy ass war in the 'Nam for no, absolutely no reason. It was insane. We in the Five remained in the U.S.A. and played the music. Now, we got to meet a lot of vets. And a lot of kids would come up to us all over the country crying their eyes out, saying "I just got my notice from the draft and I don't wanna die. What can I do?" And we'd tell them from the benefit of our experience, "Here's what you gotta do to beat the system...just prove to them that you're crazy." Essentially.

And we started losing a lot of friends at that point in time and the reason that we would say, that anyone would say that we were like Vietnam vets is that we were veterans of Vietnam, but we were here on the home front, defending the right of America to say, "No, this has to stop."

Remember the Chicago Democratic National Convention, the riots in Chicago? Well, at that show that we played in Lincoln Park, there were supposed to be six or seven other groups showing up...and no one showed up but us. And we went into the first five songs, I think we got to "Starship," and that's when the police with the batons and the horses in the back, and the crowd started throwing bottles, and that's how that particular riot in Lincoln Park took place.

There were five or six different riots, and a lot of people got really fucked up, really hurt. And we got our little blue Chevy van with a big "MC5" on the side, and we got off the stage and everyone shuttled us off and out of there straight away, and then at that particular point they cleared out that whole park, maybe 3,500 people.

So...you could compare us to being, in a sense, a Vietnam vet, 'cause we weren't in Vietnam, we weren't getting shot at, but we took the bullets here for the guys taking the bullets there. So they could come home.

People gave it a lot of lip service, y'know, but when push came to shove and you maybe had to get your head cracked for believing in it and [taking] a stand, well, we took a stand. And if they wanna crack our heads again...fuck it. Someone had to do it. And actually the MC5...excuse me, Stooges, and excuse me Ted Nugent, Bob Seger, all the rest of you fuckin' putzes, when it came down push to shove, and actually when interviewers would say, "What do you think about this," we told the truth.

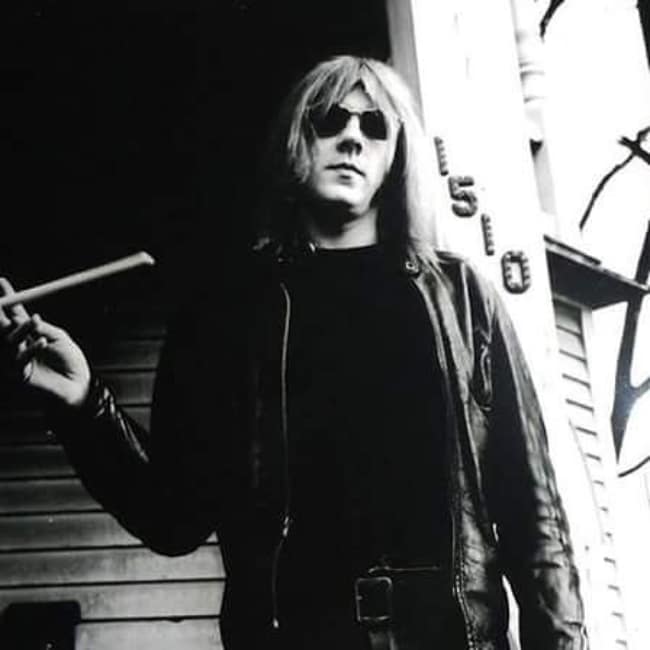

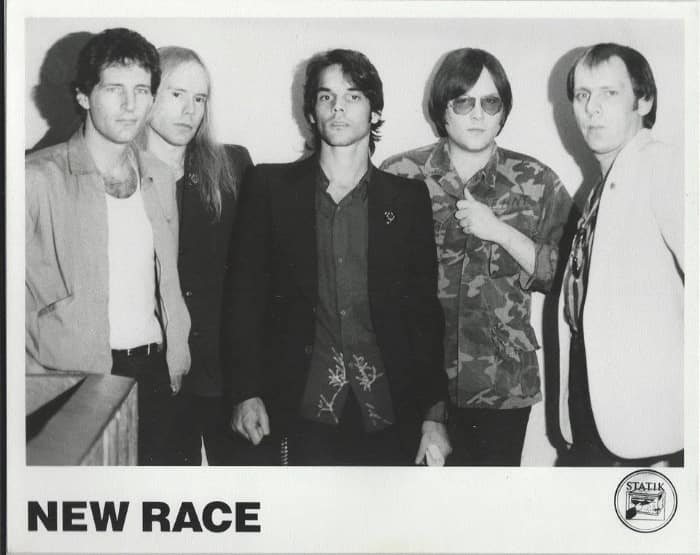

New Race promo photo.

K: I think there's a whole bunch of kids out there today who would be real receptive to the music you guys made if they could hear it.

D: Yeah, if they knew about it. It's in the archives. Whenever I get an opportunity to speak to someone like you, or anyone who wants to do a decent job of letting people know that this band did exist, I'm always here to help. I just spoke to Becky [Tyner], and she said that her daughter Amy was in Europe with Chumbawamba, and they're MC5 fanatics. So you've got Rage Against the Machine, Nirvana, Pearl Jam; y'know, the crosshairs sorta center on whatever you hear...these musicians are aware of the Five. Which makes me very, very proud.

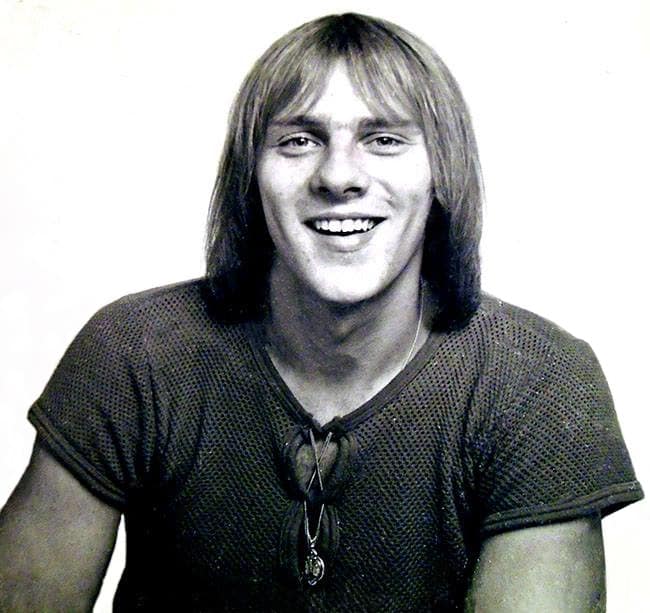

Dennis Thompson (rear) with Fred Smith, Wayne Kramer, Rob Tyner and Mike Davis.

Dennis Thompson (rear) with Fred Smith, Wayne Kramer, Rob Tyner and Mike Davis.