Now, a lot of folks have been waiting what feels like an awfully long time for this to emerge. Truth to tell, even approaching a biography of Nick Cave's life is not for the faint-hearted (as I discovered with my book on The Birthday Party way back when). I mean, Cave has lived such a huge life, such a busy, controversial, complicated life, and second, because the man has such a huge, contradictory and 'problematic' personality, that any writer who attempts a book about the man will inevitably run afoul of issues such as pin-pointing exactly 'what did happen when ...'.

When I wrote my own book on The Birthday Party, I either let people tell it, or else tried damned hard to state only what I'd been told by several sources (not just one). My opinions were obviously just that. I suspect this issue of accuracy occurred with Ian Johnston (another Cave biographer) as well - at the beginning of his book there are some very specific-sounding material on Nick's early life which was suspiciously uncredited, which lead me to assume he interviewed Nick at length, but was for some reason not allowed to quote him. But Mark ... well.

Who the fuck is Mark Mordue anyway?

Mark Mordue is a writer, and an award-winning poet whose poetry, remarkably, stands above the morass of modern poo-etry and defies the first thought into your head when you heard the phrase "award-winning poet". More importantly, Mark also has the temperament and courage to go forth and fuck up, as well as go forth and conquer; combined with this guts and determination (or damn-foolishness, if you like) he also has the ability to ponder, and think about stuff.

The result is a thoughtful, often very funny, occasionally cider-acid, penetrating and absorbing book on a man whose early life overlapped so many others. The early Nick Cave was a talented, confusing, very funny bloke in a band, Mark shows us that, but also provides a nod to the future. It's a damn difficult tightrope to walk, but he does so with aplomb and accomplishment.

Instead of one of those mammoth doorstop-style rock bios (on the boys by the boys and for the boys) which turn up each Krimbo (do we really need another roach-squasher on Jagger or Bowie or Bono?) which try to stuff all the toys into one bulging sack, Mark realised such an approach won't wash.

So at the beginning we see Mark apprehensively interviewing his subject some distance into Cave's career, explaining matters as they were back then, occasionally referring to events and stardom "yet to come". If you're looking for a book to resemble a family history, fuggeddabout it. Sensibly, rather than take us through the dreary "subject was born of..." -style chronology and nit-picking genealogical nonsense, Mark tells us of the journey he's been on over the last gawd-knows-how long.

He's really done his homework, too: interviewed just about everybody, and the writing and construction has clearly involved large quantities of time, international travel, innumerable couches and the kindness of many strangers. I love the fact that he's also done something that not enough male rock writers do - he sought out the women: from Tracy Pew's mum to Tobsha Learner, Bronwyn Bonney and Karen Marks ... as I discovered in my own book, once the names start to appear, and you interview them, the potential money-pit, time-pit and brain-sink just expand into the stratosphere. At some point I realised that even if I cloned myself, all I'd achieve is that more and more people would be contacted and interviewed and I'd be even further away from completing the book than ever.

So I suspect Mark's book has been rewritten, rejigged, re-approached and reinvented more than a few times as he considers the rolling revelations which his other interviews will have provided. Also, of course, there are veritable avalanches of material out there; for at least 35 years there have been people so obsessed with the minutiae of Cave's life that when the internet arrived, slowly but surely a vast swirling blizzard of information, misinformation, assumptions and presumptions began to cloud matters - as if they weren't murky and confusing enough already.

A quick word about books and publishing. There's a bloody good reason that writers of non-fiction these days state that any mistakes or goofs or downright inaccuracies are their own fault: that's what the public think. The truth is that is all books are finally put together in a weird Martian time-slip between author, publisher's editors, proof readers, typesetters, and so on. Some publisher's still produce 'proof' copies - which may or may not include errors.

25 years ago or so I remember cringing in horror at the typo 'AD/DC' in my book. Could I really have made that blue? I still recoil at the thought today. The manuscript I sent did not have that error (I checked). But mistakes and errors of judgement occur. In another book, the typesetter/editor altered my term 'cod-British accent' (meaning put-on British accent) and, I assume because they'd never heard the term, assumed I'd made a typo - so it emerged in print as 'cold British accent', which was, thankfully, reasonably accurate, but not what I'd written. So there are creeping inconsistencies in books.

On page 221 in "Boy on Fire", Mark paraphrases and quotes from my book, citing Dave Graney (it's a damn fine quote, too, thankee Dave). But I realised that the chum who provided the bulk of the information in that piece, Paul Slater (of "It's Always Rock'n'Roll" on 3D Radio fame), is absent. My book, of course, didn't have a lot of space for fancy stuff like footnotes and references.

On page 179 of Mark's book, he refers to the Boys Next Door, at their first gig, getting 'a punk crowd slamming'. That comes across as a straight statement, not as a wry comment - the truth is that back then most folks didn't dress especially 'punk' (like in UK, most folks saw the early Clash in tshirts or cheesecloth shirts and jeans, the 100 Club was one thing, Barnsley was another), and 'slamming in the pit' didn't appear in Australia (to my knowledge) until 1984, after we'd read about it in Maximum Rock'n'Roll - I first encountered it in Adelaide at a sweaty and muddy Grong Grong gig at the Flinders University Bar.

On page 280 there is one bona-fide author error. Toby Creswell, in Rolling Stone's review of "Door, Door" nodded at their obvious Bowie, Roxy Music and Ultravox influences. When Mark writes that that last comparison horrified the group because they were "now cast in with Ultravox and the latest pop fad, New Romanticism". Well, no, that wasn't the reason, not quite. While the folks developing what would become New Romantic in UK clubs in 1979, it was not until 1980 that the movement began to gain traction and popularity, some 12 months and 12000 miles after the BND had given up their eyeliner and puffy shirts, but just in time for The Birthday Party to mock them with their own poisonously funny take on the UK underground's/ clubland's pretentious haircuts.

The Ultravox most people are familiar with had their first release in late 1980, while Ultravox!, John Foxx's outfit (originally Tiger Lily) were formed in 1974; by 1977 they had a record contract and were prowling Europe and UK and not making a lot of money, so they dropped the '!' and kept going. But after 3 LPs the record company dropped them on New Years' Eve, 1978. That said, Simon Le Bon once commented that Ultravox! were their generation's Velvet Underground. No, at a guess the Boys Next Door were horrified at the comparison because Ultravox(!) were then regarded as incredibly pretentious Roxy Music and Bowie pretenders. Backwards clones, in fact, while Bowie was still forging ahead at that stage, while Roxy Music were, effectively, a past influence. The Boys Next Door felt they were moving forward, not back.

But such trifles are unimportant. What is important is the breadth and understanding of what Mark's unearthed, and his masterful approach. "Boy on Fire" is a damn fine book. Because we are become utterly fascinated with this strange man and his super-real and mythological (think of Sidney Nolan's Australia) background, when Mark allows us to peer into Cave's boyhood (and, briefly but pertly, ancestry) around page 60 (!!), we're struck by just how drawn-in and addicted we've become.

Most enjoyable. Another enjoyable feature is that as you read, you make frequent stops to relisten to old favourites (from Cave's influences to his current work), and many of those songs which made the 1970s so 'special'. Basically, you go into a world you kind of remember, but becomes that much more vivid.

Also quite sensibly, Mark allows us to form our own opinions about Cave's complex and over-analysed character. And most helpfully, over the years Cave himself has developed as a man, and seems less paranoid and peculiar these days. And Mark has had excellent access, as well as his fabulous peripheral interviews, so the finely-made mesh he's made of all this (which most would find unutterably complex beyond belief) is genuinely remarkable.

For example, over the years Nick has, from time to time, embellished (and, we suspect, outright fibbed) about his life. Hardly surprising; when you consider that journalists and other writers are always looking for a story, and when 'the subject' sits down with them, somehow he's got to come up with something interesting, even though all he's done for the last six months was drinking and watching TV. Compare that to the people Mark has pulled out of the past whose memories of Nick and his life notably differ with Nick's quoted statements. Even when they don't contradict, they're often ... not the same.

Truth to tell, there were always going to be contradictions aplenty in a book on Cave, and Mark is the first person I can think of to attempt to make sense of them without egotistically lecturing us or making a series of 'critical' judgements. That he succeeds so damn well is a tribute to his abilities as a determined type, as well as being able to put everything together and make such a clear sense of it all. It's also a hoot of a read.

Hell, there's so much new and interesting information here that even the footnotes at the end are worth the price of admission. In fact, you'll be so damned enthused that you'll pester the publisher and ask, When's the second book coming out?

Like I said, top marks (or three 1970's muttonchop icons)

Like I said, top marks (or three 1970's muttonchop icons)

P.S. God, but Mark set himself a Herculean task. So much happens in the period 1980 to 1983 that one assumes that either the resulting book will be a massive doorstop, or two volumes. The great news is that Mark's up to it.

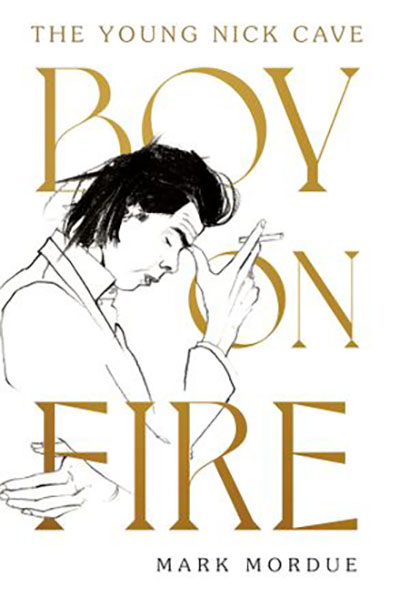

Boy on Fire. The Young Nick Cave

Boy on Fire. The Young Nick Cave