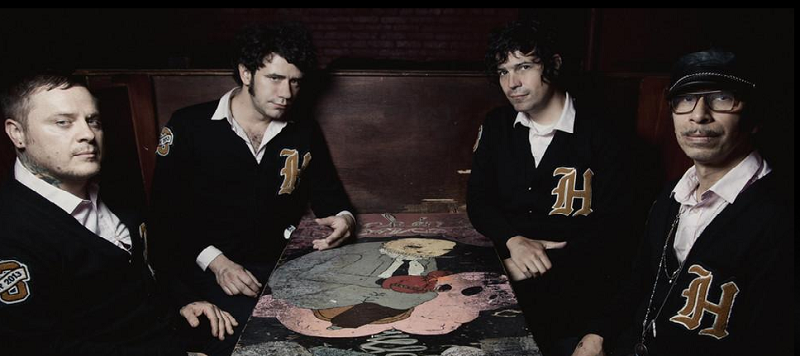

Guess who's coming to dinner? Kid Congo Powers (right) and the Pink Monkey Birds.

Guess who's coming to dinner? Kid Congo Powers (right) and the Pink Monkey Birds.

Kid Congo Powers’ musical career is a lens through which can be seen some of the most intense and evocative music of the last 40 years.

Born Brian Tristan in the Los Angeles suburb of La Puente, Kid Congo Powers famously met Jeffrey Lee Pierce in the line at a Pere Ubu concert. Pierce was the president of the LA chapter of the Blondie Fan Club; Powers was the president of local chapter of The Ramones Fan Club. Pierce recruited Powers to join his fledgling band, Creeping Ritual, later to become The Gun Club.

In 1980 Powers joined psychobilly band The Cramps, who’d recently moved to LA from New York (it was Cramps lead singer Lux Interior who bestowed Brian Tristan with the moniker Kid Congo Powers).

Andy Venturini photo.

Andy Venturini photo.

Powers remained friends with Pierce, re-joining The Gun Club in 1983 for the band’s Australian tour, and dropping in and out of The Gun Club for the next 12 years (Powers shares with Pierce the honour of playing in both the first and last ever Gun Club shows, having re-joined The Gun Club for a few shows shortly before Pierce’s death in 1996).

Over the course of the next 30-odd years, Powers pursued a colourful and eclectic musical path, including Fur Bible with Gun Club and former bass player with The Bags, Patricia Morrison (and, initially, Tex Perkins), Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds, Congo Norvell (with Sally Norvell), Knoxville Girls (with Bob Burt, Jerry Teel and Jason Martin) and, most recently, Kid Congo and the Pink Monkey Birds.

A prodigious drug taker and drinker for much of his career, Powers cleaned himself up some years ago, deciding that his reliance on alcohol and narcotics was diluting his passion for music. (Powers is so responsible these days that when I discover that I’ve accidentally wiped the tape of our phone interview, he offers to re-do the interview again a week later.)

When I ring Kid for the “replacement” interview, the now Connecticut-based garage rocker is working on his forthcoming biography, due for publication later this year on In the Red’s newly established book publishing imprint.

You were famously the president of the Los Angeles chapter of The Ramones fan club. When did you first hear The Ramones, and how did that affect you?

You were famously the president of the Los Angeles chapter of The Ramones fan club. When did you first hear The Ramones, and how did that affect you?

I had first seen a photo of The Ramones, and that was enough to send me into some sort of teenage tail spin. Glam rock had ended, disco was assuring its way in, the disco ball was tending to tempt half the people away from glam rock, because people were looking for nightclubs to go to, and something new. But for me, The Ramones came along, and spoke to me in every way, just the photo of them.

These guys in jeans and leather jackets, bowl-head haircuts, standing in front of a trash infested brick wall. It just conjured up every amazing thing I loved about music. I loved ‘60s music, especially psychedelic music, and there was something mysterious about [The Ramones], the haircut definitely, the whole look and the attitude.

Then I’d read about them, and they’d have songs like “Beat on the Brat”, and I’d be like “What is going on?” So then the record came out, I specially ordered it to my local record store, and I went down there on the morning of the release, I decided to have to wait in line so I didn’t miss getting a copy.

Of course, I was the only person waiting for it!

I took it home and lost my mind. It was everything stupid and smart, the compactness of the songs was like something from outer space, something you’d never heard before.

I’d been to see The New York Dolls, The Stooges, so I knew the lineage of the music, the Detroit/MC5 scene, I was aware of that and a fan of it, but The Ramones just cut it to the quick. There was nothing like it, it was energising. I jumped up and down on my bed in my parents’ suburban house and was converted on the spot, right there, never to return to normal!

As a teenager in LA, were you a regular visitor to places like Rodney Bingenheimer’s English Disco?

Yes, I did. I spend a lot of time outside of Rodney’s English disco because I was too young to get in until later in the evening. There would be a big crowd of young kids, a lot of young girls obviously who the older guys liked. We were tolerated - we were younger kids who weren’t groupies, we just liked the music, we were music fanatics and we were tolerated because of our youth.

I met people who I still know today, in the back alley of Rodney’s disco, drinking beer and waiting til it was late enough to let everyone in. I’m sure the laws were more lax then, as far as getting raided goes, because there were a lot of teenage kids there. But it was fun, it was great, we were all a bunch of kids then who were excited to be around music. And we knew that the glam rock stars hung out there.

So you’d go along and think “Maybe Marc Bolan will be there” or something. It was just very exciting, and of course you went there to dance. The music was mostly British, glam rock, coming from England that you didn’t hear on the radio. Rodney Bingenheimer was up on all of this and played Roxy Music, Sparks, David Bowie of course, T-Rex, Mott the Hoople. I learnt a lot about music from there, and magazines, and a lot of punk rock came from there too.

A lot of the kids were 15 or 16-years-old, someone like Joan Jett, who’s the same age as me, was there. And there were people younger than me were there! It was our land of misfits before punk rock. It was very fantasy driven, a lot of fashion, a lot of crazy David Bowie fantasy, rock-starry fantasy. Punk made a different kind of rock star, the anti-rock star. That’s why The Ramones seemed so great - they were anti-rock star, but in fact a very focused rock star look. You would think it was natural, but was probably pretty orchestrated! But to the teenage everything is real, that fantasy is real. And a lot of it is still real to me, half the time!

A few years later you started playing with Jeffrey Lee Pierce in Creeping Ritual, which became The Gun Club. Before then you’d never played guitar. Did Jeffrey Lee Pierce teach you chords, or just the feel of the guitar?

The main reason that Jeffrey taught me guitar was that I had no idea how to play guitar, so he said ‘This is a way to play guitar really fast’, and that was to tune it to an open E chord. That was the way a lot of blues players played to play slide and guitar. There was interest in the blues, and our interest came from Bo Diddley, the Stones, Dylan, Thin Wild Mercury phase, things like that were an influence. Jeffrey gave me that open E guitar and gave me a Bo Diddley record, and sai: “Learn this song, it’s called ‘Bo Diddley’s a Gunslinger’, and it’s one chord”. I had to put my finger over the fifth fret and just practised a Bo Diddley rhythm with one chord, and I haven’t stopped doing that since.

That was my way in, but we were also very influenced by New York bands, like The Cramps obviously, but other bands, like the No Wave bands.

I’d lived in New York, and so had Jeffrey. Something we bonded on was that we had both gone seeking something in New York. We were aware of the No Wave thing going on, people like James Chance mixing James Brown with free jazz and Albert Ayler. There was this nihilistic attitude, Teenage Jesus and the Jerks, very anti-music music, but super interesting.

Also, Lydia Lunch, Pat Place from James Chance’s band the Contortions, he played slide guitar, and they were playing it more as an expression than they were playing the blues. But it really spoke to me. So I had those two things in mind: some roots music, and some anti-music of the New York No Wave.

What was the contrast between the New York punk and no wave scenes and what was going on in Los Angeles at the same time?

Very different, because the coasts are very different. The east coast is far more cerebral, the east coast doesn’t suffer fools lightly. LA people are very into having fun and having a good time, more theatrical. I think Hollywood played a big role in it, especially in a visual sense. That was the kind of contrast: people in LA pretty much thought New York was pretentious, whereas New York thought LA was a big bunch of fluff!

That was the contrast, at least superficially. There was great things going on in both places, and I was well aware of that. I wanted it all - I wanted to know it all. So I spent time in both places.

That’s the thing when me and Jeffrey started The Gun Club, we really thought we’d experienced, I’d been to London already, I’d spent time in New York, he’d also spent time and tried to get something going on in New York with a friend. When we came back to LA, even though we might not be able to play, we had this experience, of knowing there was more going on than was in LA, and we thought we could make something that was a little more wide-ranging. That was definitely in our mind when we made a band. We would incorporate all this stuff we’d experienced. We didn’t have the skill to do it, but we definitely had the intention.

It was Lux Interior and Poison Ivy who gave you the musical nom de plume “Kid Congo Powers”, when you joined The Cramps. Did that provide you with an identity that you could grow into?

Certainly. It was great. Lux was always appointing people roles. He was very good at doing that. He even made up a role for my mother. He said her name was “Alura Monsanto”, which was a Mexican vampire actress! One time my parents came to see me when I was first in The Cramps, and he introduced her from the stage and she really got into it. He would assign roles to people, with love.

Kid Congo Powers was definitely a character of sorts. It wasn’t me, but it gave me something to look into. It was based on Kid Thomas, this old r’n’b singer, New Orleans shouter, and he had this crazy jellyroll haircut. There were signposts and touchposts to that. I was a big fan of The Cramps, and I was a big fan of Bryan Gregory, my predecessor, huge fan and friend. So I wanted to inhabit what he did, I had to make sure The Cramps stayed The Cramps. I had to live up to something. They were pretty big high-heels to fill. The idea of being called Kid Congo Powers gave me a new licence to explore more.

A few years later, after you’d re-joined (and then left) The Gun Club, you did the Fur Bible project with Patricia Morrison, initially with Tex Perkins before Tex went back to Australia. I’ve read that you didn’t think much of the Fur Bible EP when it was released. What do you think of it now?

I think that was a weird time in my career, a bit of musical identity crisis. I think that it was a fine band, I just had very high expectations of myself and other people. I think me and Patricia thought “Well, we’ll just do what we do and it will be great” and then we realised we had to have more than that.

Without Jeffrey’s songwriting, we had to come up with something. There was a pedigree and an expectation on our part that it had to be fully-formed immediately. I don’t know why. We were young, so it was a case of trying to top the last thing that I’d done. The Gun Club was a hard thing to top. I think there was a lot of stuff being thrown together, and that’s what I felt about it. I didn’t think we’d thought enough about it, that we’d tried enough things. We had tried to import Tex and do that, and that didn’t work out, for many, many reasons.

Now, I think the recording is great. But at the time it just wasn’t what I wanted to do. To me it was a failed experiment.

Scrolling forward some years, you were very emotionally affected by the spate of AIDS-related deaths in the late 1980s and early 1990s. How did your emotional state manifest itself in your music?

That’s manifest in several different ways. It was a very traumatic, very blind-sided punch in the face. Suddenly so many friends, colleagues and peers were dying, a lot of artists, a lot of musicians, a lot of fans, friends of mine that were fans, the gay rockers, suddenly everyone was getting sick and dying.

At first you didn’t know what it was. As it happened, musically it manifest in different ways. Initially it started by looking for some sort of solace. There was a lot of anger about it. Diamanda Galas, her brother was dying and she was doing very angry performances. I was looking to do something that was more … trying to find beauty or comfort, and that was when I started doing Congo Norvell, with my friend Sally Norvell, because we had a mutual friend who’d recently passed away.

Her husband introduced me and Sally. I had just moved back from Berlin where I’d been in the Bad Seeds. Sally Norvell had been in Paris, Texas - she played a nurse in a peep show (Harry Dean Stanton accidentally goes into her peep show before he goes to Nastasja Kinksi’s). So we’d both been in Wim Wenders films.

Sally was an amazing jazz singer. I’d just got back to LA, so I thought “Let’s try something.” Our first things were doing AIDS benefits, and benefits for Act Up, an activist group. We had a band called Congo Norvell, and a lot of that dealt with disappointment and anguish of the AIDS epidemic and addressing it through music. But we didn’t get into a super angry version. We just tried to tell a story or convey a feeling. I’d just been in the Bad Seeds, and sometimes that was just like soundtrack music to stories. So I wanted to see what I could do with that, and transfer that to Congo Norvell.

What about Knoxville Girls? How did that come about, what happened to that project in the end?

Knoxville Girls was a bunch of friends on the Lower East Side of New York City. I’d moved there in the early 1990s, and Jeffrey Lee Pierce had passed away. Congo Norvell was going and not going. I was friendly with Jerry Tell and Jack Martin and Bob Burt, who were going some recording as a side project.

Bob and Jerry were in The Chrome Cranks, who were very hard-rock, post-punk, garage-rocky band. They were doing this country-ish, it was supposed to be a country project, but of course it was all mixed up, and they started calling it country no-wave. They asked me to come in and sit in on the session, and I ended up playing on most of the songs. So it was a recording project that turned into a nice live project.

We ended up making a couple of records and then everyone else got busy with other things. I think by the second record some people wanted to be more country, and some people wanted to be more no-wave, and no-one could come to an agreement on which way it would go. There was never an intention to be a gang, it was more a recording project that got some flight and play some shows. And I love those albums. And I’m now playing with Bob Burt in a band called Wolf Manhattan Project, with Mick Collins from The Dirtbombs.

On stage with the Pink Monkey Birds.

On stage with the Pink Monkey Birds.

For someone who led such a wild life back in the day, you cleaned up and by your own admission, you’re much more disciplined than you ever were. What was the catalyst for cleaning yourself up?

My health, for one! But that was not a concern at all. I think it was a general disillusionment with the way I felt. I was a junkie, a heroin addict, an alcoholic, I found myself very disconnected, turning to stone. When I finally realised I was more interested in just maintaining drugs than in making music, it scared me, scared me to death. I saw other people cleaning up, and it seemed to be working well for them.

But mostly it was that I didn’t like not feeling anything, and I didn’t like that I was losing interest in the one thing that sparked my passion, and the one thing that had led me through my life thus far, it kind of took over from rock’n’roll and my passion for music, for performing, for listening for anything.

When that came to my attention … some of it came to my attention, and some of it other people told me - people said to me ‘Look what’s happening to you, you’re fucked’. So it was a matter of preservation. It was good - my love of rock’n’roll saved me, once again - from myself!

When you were out in Australia a few years ago you recorded some songs with Spencer Jones and Kim Salmon. Do you have any idea what’s happening to those songs?

I would love to listen to them again. I would love to revisit it. It was fun stuff. We did a great improvisational, crazy piece, unlike anything you might expect us to do. There was some other stuff that Spencer wrote. We’ll have to talk about it. I’ll be there soon, and I’ll see Kim and I’ll see Spencer. I guess we’ll have to decide what to do with it.

Our first idea was that it was going to be The Butcher Shop, but Tex was too busy to come out to the session when I was there. It was cool stuff. How could it go wrong, with Kim Salmon, Spencer and me, and the Pink Monkey Birds?

You’re in the midst of writing a book about your life. Has that been cathartic, or confronting, or generally emotional?

It’s been terrifying! Horrible [laughs] But it’s illuminating to look at your life. It’s been such a long, long process. Nobody told me it was going to be so long! I’m happy I did it with a ghost writer too. I almost did that, but a few people advised me against that. I did too much much in the beginning, so they said “No, you finish this.”

It’s difficult to write about yourself. It’s therapeutic, cathartic, all those things. When I started it, and I think this, because I’m still writing at the moment, it’s going to tell me when it’s all over. I just tell the stories and I’m trying not to get too much wrapped up in them emotionally and just tell them. The process is long, and I think I’ve been through just about every emotion. I’ve loved doing it, I’ve hated doing it, loved myself in parts of it, I hate myself in parts of it, I think I did some great things, and a lot of things I thought were really great weren’t so great. And then I have to choose what is important. Right now the story is starting to come out.

It’s like solving a puzzle, but it’s weird because it’s your puzzle and you don’t even know if this piece fits or not as they slot in. But the picture’s pretty clear now. It’s a strange, weird trip.

Kid Congo and the Pink Monkey Birds

Australian Tour 2018

MAY

9 - Mojo's Bar, North Fremantle, WA

11 - Theatre Royal, Castlemaine, VIC

12 - The Croxton Bandroom, Thornbury, VIC

13 - The Brisbane Hotel, Hobart, TAS

18 - Oxford Art Factory, Darlinghurst, NSW

19 - The Foundry, Fortitude Valley, QLD