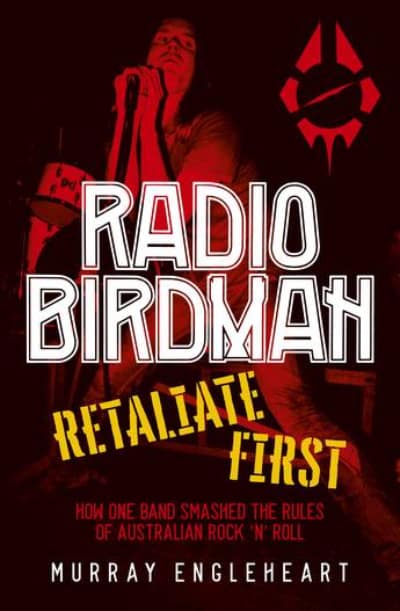

Retaliate First: How one band smashed the rules of Australian rock and roll

Retaliate First: How one band smashed the rules of Australian rock and roll

By Murray Engleheart

(Allen and Unwin)

What becomes a legend most

When the musicians have come and then leave her

What becomes a legend most

Besides being a legendary star

What Becomes A Legend Most” - Lou Reed (1984)

It’s finally here and it’s great. For the first time, the Radio Birdman story has been thoroughly told from start to dotage (if not the end) in print, and with a sense of perspective that puts contestable versions of the story in plain view.

For the first time? What about Vivien Johnston’s 1990 “Radio Birdman”? For many years it was the best (only) reference point. As invaluable as it was, it was ultimately a biography shoehorned into a university thesis, and the tenuous link it tried to make between the band and Australian indigenous culture was odd.

And there's “Radio Birdman: The Illustrated History” from George Munoz, an amazing visual record of the first life of the band but doesn’t try to be commentary.

Murray Engleheart’s “Retaliate First” is an effort to re-tell the story as it should be told and it’s an invaluable companion to Jonathan Sequeira’s brutally honest “Descent Into The Maelstrom” documentary.

Written over half-a-dozen years and after 150 interviews, “Retaliate First” had the sort of gestation that we’ve come to expect from Australia’s Most Complicated Band. Constant fact-checking and cross-referencing were required. Just because a myth has been made doesn’t mean it’s 100 percent true. The unspoken pressure to embellish a legend already writ large must have been significant.

There were always going to be complications in bringing this story to print. Tinges of rancor from former members linger to varying degrees. Some of the interviews must have been like walking on (bird) eggshells. As far as can be determined, all parties have had their points-of-view ventilated, with only some gentle editorial nuancing applied. A couple of the more florid direct quotes can be read as self-aggrandising. There’s a parallel to the documentary there: Read the book properly and you can draw your own conclusions.

For an underground band, Radio Birdman’s members haven’t been invisible since the 1996 reformation. They might have been notoriously prickly in the days when they were receiving sporadic press attention, but dealing with the media devil became part and parcel of their second life as a touring band. Engleheart draws on the public record but not overly so. You might think that every story to do with Birdman’s first life has been told. Not so.

Engleheart went digging for nuggets and finds a few. Did you know Jim Carrey was president of the Canadian Radio Birdman Fan Club? That Rick Grossman was a Funhouse roadie on top of being a Hellcat? Or that Radio Birman was served tea by inmates of Parramatta Jail after a gig on the inside? Truth is often weirder than fiction and there’s enough anecdotal gems and oddities in the 437 pages to keep Birdman tragics happy.

Engleheart is one of this country’s best rock and roll writers with a concise, punchy and engaging style. He knows that quotes are like the oars of a boat – they propel the vessel through the water when applied at the right time – and Murray knows how to row.

If there’s a unifying thread running through the story, it’s the sense of Us versus Them. At its extremity, you might have also called it clinically undiagnosed paranoia. It’s so strong that even people on the band’s periphery have caught doses of it down the years (with the author not immune, judging by one odd recent dealing.)

You can trace Birdman’s history to two or maybe three key points where things took a twist. Engleheart’s narrative covers each of them skillfully. The first was the RAM Punk Rock Thriller which escalated the band’s profile and nudged Birdman into the recording studio. The closure of The Funhouse is another, as the band crossed-over to bigger crowds and exponentially larger venues.

The other inflexion point was Deniz Tek’s 1977 trip home to Ann Arbor. You couldn’t begrudge the then-medical student a break back home. While he in the US re-meeting his folks and jamming with Ron Asheton, however, in-fighting, between Rob Younger and Ron Keeley escalated. Warwick Gilbert wasn’t a happy camper after the band’s recalibration to accommodate a returning Pip Hoyle, a move taken without consultation that dramatically changed the musical dynamics and left Chris Masuak quietly bewildered

Tek’s (brief) introduction of uniforms and armbands was an attempt to re-instill a “band as a gang” mindset but it ran against the grain of a couple of members and fed into the ludicrous “Fascist band” narrative that the band’s detractors were running.

With the advantage of hindsight, the personnel fissures had already begun. The introduction of manager George Kringas into the organisation, again apparently with minimal consultation, continued the trip to the endzone.

About that Fascism thing: You wouldn’t see a hysterical woman pulling down the Birdman banner at a show in today’s world. There’d be an organised chorus posting about it on X (aka “the platform formerly known as Twitter”) and the band’s enemies would use the resultant pile-on to declare the Radios as cancelled.

The Dean Incident, in which persons unknown lodged a letter with the boss of University of NSW claiming Deniz had pushed hard drugs onto their daughter, has finally been told. In the cold daylight of a cynical Internet age, it reeks like a stitch-up of the highest order that would have fueled collective paranoia and given Tek grounds to take up the drawbridge and lock down.

Part of Radio Birdman’s allure was its sense of mystery. Red and black is an unbeatable colour scheme. Boys love war toys and the imagery reeked Dadaist cool. If you want a visual sense, dive into the numerous previously unpublished photos Engleheart has compiled.

The existence of a somewhat closed “scene” of fanatical supporters with their arms wrapped tightly around the band was undeniable and Engleheart’s book takes you right inside it. It was a natural expansion of the “Us vs Them” ethos and a basis for its “no compromise” rule.

It's great to see exposure given to the pivotal roles that followers like Gearside, Lee Taylor, Jules Normington and Angie Pepper played in the early Birdman days.

Scenes can disappear up their own orifices. This one included/attracted some talented people but also generated snobbery from some participants. This manifested itself in Birdman offshoots like the Hitmen being kicked into touch the moment they jumped onto the agency-run, suburban gig circuit. Surely this was music to be taken to the masses to facilitate their conversion?

The book’s portrayal of the sense of loss for followers with the Funhouse’s closure is palpable. The bashing of then-Psychosurgeons singer Paul Gearside by bikies was the catalyst, but the point is well made by the author that the band’s informal lease on the upstairs room at the Oxford Hotel had run its course, anyway.

Detractors have it that Radio Birdman headed offshore at the end of 1977 and failed miserably. Rob Younger is quick to set the record straight. His observation that the classic incarnation had built-in obsolescence because of the personalities of the people involved is the most incisive comment in the book.

The story didn’t end in 1978 and you're an I-94 Barfly you probably don’t need a blow-by-blow account of how the Australian (Sydney in particular) underground exploded with a mix of original, faithfully derivative and slavishly devoted bands. Various Birdmen convened their own groups after youngest member Masuak made the initial leap, with the Hitmen, Hoyle, Tek and Keeley re-surfacing in The Visitors. The aftermath is related succinctly, but well.

The band has been honoured. This is the Radio Birdman book we needed. If only the band’s original and biggest fan Alley Brereton was still around to read it.

![]()