SPENCER P. JONES

SPENCER P. JONES

1956-2018

In "Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance", Robert Pirsig interrogates the very nature of quality through the lens of motor mechanics. Care and Quality are internal and external aspects of the same thing. A person who sees Quality and feels it as he works is a person who cares. A person who cares about what he sees and does is a person who’s bound to have some characteristic of quality.

Spencer Jones knew a thing or two about quality - especially musical quality. Born in 1956, the Year of Elvis, Spencer wanted to be a working musician as long as he could remember. Spencer’s family moved from the regional town of Te Awamutu to Auckland in 1965, the same year the British invasion swept through New Zealand, with tours by The Rolling Stones and, infamously, The Pretty Things.

Spencer’s grandfather was a gifted musician; his mother, too, was born with a natural ear. Recognising Spencer’s musical abilities, Spencer’s elder brother Ashley recommended his parents buy Spencer a guitar.

Carbie Warbie photo

Spencer and his mum Jose.

Spencer and his mum Jose.

Not for the first time Spencer’s life was irrevocably changed by tragedy. Two months after Ashley was killed in a freak accident in 1970, Spencer’s parents honoured Ashley’s suggestion and gave Spencer his first guitar. Spencer also inherited Ashley’s rich record collection: The Beatles, The Rolling Stones, The Who, Hendrix. At the age of 19, Spencer packed his bags and moved to Sydney, ostensibly as a pit stop en route to England, where Spencer had decided his future lay, as a rock’n’roll star.

Spencer never became a rock’n’roll star, yet he forged a legend as towering as any Antipodean musician of his generation. Spencer is a Zelig-like character, appearing at significant moments in musical history. When Radio Birdman waved the flag against the jive at the Oxford Tavern in 1976, Spencer was there. Spencer arrived in Melbourne in 1978, just as the Carlton scene was fading, but early enough to witness the gestation of the Melbourne punk scene.

In 1978 Spencer moved to Melbourne, and by the end of 1979 Spencer was playing in Cuban Heels alongside future Paul Kelly guitarist Steve Connolly. Connolly and Spencer’s symbiotic platonic and musical relationship would have lasting impact on Australian music: Connolly taught Spencer punk rock; Spencer tutored Connolly in the country rock guitar styling that would underpin Connolly’s signature sound in Paul Kelly and the Coloured Girls.

In North 2 Alaskans and Country Killed, Spencer was the bridge between the Melbourne comedy and the Australian independent music scenes. Two decades later Spencer reprised that role when he played guitar in comedian Anthony Morgan’s short-lived "Ron" spoken-word comedy-rock troupe.

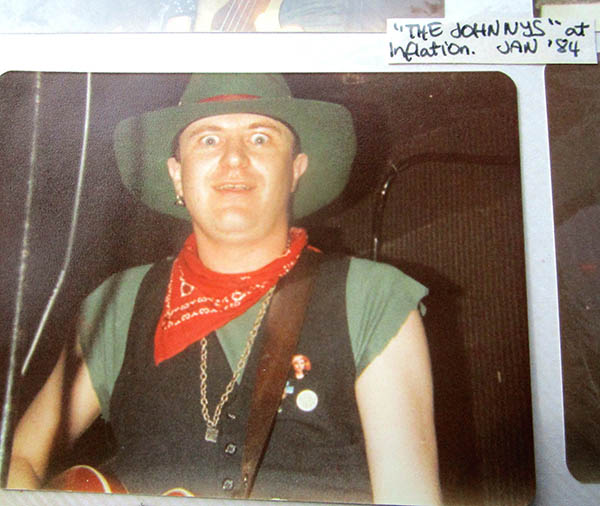

Moving to Sydney to join The Johnnys in March 1983, Spencer was a protagonist in the Surry Hills music community, one of dozens of musicians, artists and fans cramped into the narrow terrace houses in the former slum neighbourhoods of Sydney’s inner-city suburbs. The Beasts of Bourbon were a natural product of this fertile environment.

Over the years the Beasts would evolve from shambolic covers band into powerful rock’n’roll force, to seasoned caricature. Tex Perkins was the figurehead of the Beasts, Kim Salmon the intense artistic presence, James Baker the charismatic link back to rock’n’roll’s troglodyte origins. But Spencer was always the beating heart of the Beasts.

Debbie Lee photo.

Debbie Lee photo.

The Johnnys catapulted Spencer into the rock’n’roll lifestyle. Renowned as the hardest working band in Australian rock’n’roll, The Johnnys lassoed, yee-hahhed and drank their way into Australian music legend. When Radalj left the ranch in early 1984, Spencer took on the mantle of singer and principal songwriter.

Serendipitously, Spencer was in the right place at the right time in September 1983 when half of The Gun Club quit just as they were about to board the plane to Australia. Spencer and Billy Pommer were drafted in to create a make-shift Antipodean Gun Club, with original Gun Club guitarist Kid Congo Powers flying out a few days later. The ever-volatile Jeffrey Lee Pierce spent much of the tour at loggerheads with the tour promoter, but Pierce loved Spencer.

Increasingly frustrated by the artistic limitations of The Johnnys’ cowpunk shtick, Spencer sought to broaden his musical horizons. The Beasts of Bourbon re-formed, released a couple of albums and became a real band. When Ian Rilen and Cathy Green played Spencer a song they’d written recently for their post-X band, Spencer jumped in with a sparkling guitar melody that would come to define Hell to Pay’s first single, "Saints and Kings".

1989, the year Spencer described much later, “as when everything went to shit”, was replete with familial tragedy and emotional upheaval. The break-up of Spencer’s marriage was the catalyst for the songs that would appear on Spencer’s debut album, "Rumour of Death", one of the great Australian albums of the era – in fact, any era.

Spencer moved to Melbourne and became a leading figure in the so-called Melbourne Music Mafia. Spencer was the gun for hire, a musician whose aptitude and empathy for music was in constant demand, from These Immortal Souls with Rowland Howard, to Working Class Ringos with Maurice Frawley.

Spencer even joined Paul Kelly’s band, adding a layer to Kelly’s songs hitherto unseen – it’s almost impossible to contemplate "How to Make Gravy" without Spencer’s slide guitar part. To Spencer, it was just about the quality of the music: he only cared about playing with quality musicians, and supporting and encouraging the qualities he saw in others.

It’s easy, lazy in fact, to define Spencer by reference to the tall stories and amusing anecdotes in which he features as a protagonist or a punch line. There’s almost as many stories of The Johnnys’ alcoholic antics as the number of shows they played. The Beasts of Bourbon morphed into seasoned character actors, indulging whatever narcotic or alcoholic pleasure was presented before them. Tales of shabbiness and shambles at Spencer’s tequila-rich solo shows are as thick as the sticky carpet of the venues he patronised for so many years.

Spencer is defined by his warm personality, his charm, his love of music, his sense of humour, his generosity, his sensitivity. Jon Schofield, bass player with Hell to Pay, describes Spencer as "the gentleman of Australian rock’n’roll". Turn over any precious Australian rock of the last three decades and you’ll see Spencer’s influence somewhere in its formation. Even as he became an elder statesman of rock’n’roll, Spencer was still exploring and nurturing new music and young musicians, whether within his own band, as producer or just general supporter.

Carbie Warbie photo.

Carbie Warbie photo.

Spencer was no saint, nor would he want to be canonised as such. He was flawed, just as we all are. By his own admission, Spencer was easily led, indulging in activities that would haunt him years later. Spencer could be flaky, frustrating, sometimes unreliable. His missteps arguably cost the Beasts of Bourbon a shot at commercial fame. Had he been more disciplined, Spencer’s solo career may have transcended its cult existence. But if Spencer had focused on popularity and fortune over quality and care, he wouldn’t have been Spencer.

To survey Spencer’s stellar career is to bear witness to quality in so many varied guises: from country to swamp, from soul to punk, from blues to folk. Spencer is protagonist, mentor, cameo actor, director, producer, always taking care. Take Spencer Jones out of Australian music over the last 40 years, and you’re left with a gaping void.

Then cancer surfaced.

Even as Spencer’s health declined, he was still excited about what lay ahead. “I’ve got more music to make,” he promised me one afternoon, as we sat down for one of the many interviews we conducted for the biography project he graciously agreed for me to undertake back in late 2014. Spencer even contemplated a recalibrated Beasts of Bourbon line-up, a different mixture of personalities to overcome the Beasts’ perpetual ego-laden dramas.

In the end, Spencer’s body, which had tolerated so much over the years, signalled impending defeat. Spencer was determined to play at Beasts bandmate Brian Hooper’s benefit concert, and he did. There has rarely been a more emotional event in rock’n’roll history.

Spencer’s last public appearance came at the end of Kid Congo’s show at the Croxton Park Hotel in Melbourne. Tired and noticeably frail, Spencer slid into the simple blues riff of The Gun Club’s "Jack on Fire". Kid Congo hugged his long-time friend, and saluted him to the crowd.

There has never been anyone like Spencer; there will never be another like him. Thanks Spencer. Thanks for showing us all a real good time.

Spencer is survived by his wife Angie, son Alvin, sister Jan and mother José.

The public funeral for Spencer P. Jones will be held on Friday, August 31 at 1pm at St Mary’s Church, St Kilda East, followed by a private burial. A memorial event is scheduled for The Thornbury Theatre from 5.30pm.

Spencer and Angie. Amiss Kat photo.