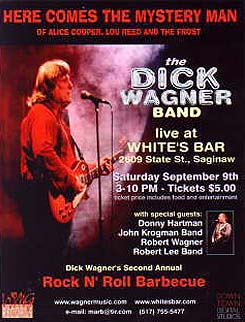

Geoff Ginsberg: Back in '99 I was living in Michigan and caught wind of a Frost reunion show in Saginaw - an hour or two up the road from Ann Arbor. And the opening act was going to be Cub Koda of Smokin' In The Boys Room [my very first 45!] fame. Cub and I worked for the same company, not that I had met, or even seen him there. There were a bunch of different ventures under the one umbrella. One of those was a web-zine. They had gotten a whole bunch of legendary journalists and stories/interviews with such A-listers as Cher and Sheryl Crow. I was not involved in the web-zine. But I asked the editor, a famous guitar mag guy closely associated with one, Edward Van Halen, if he could get the Cubmaster to hook me up with free tix for the big Frost show. Now, you have to understand, this editor was a guy who is operating on a whole different level than say, me. He's always thinking two moves ahead. He didn't hesitate for a second: "The intro and Sweet Jane on R&R Animal is

the best guitar playing ever on record - why don't you interview Dick Wagner??!!" Of course I said sure - even though I had no idea how to do an interview.

So his manager and I set it up and I went up there a week before the big Frost show. And it really was a big show. Packed symphony hall - beautiful classic cars on stage - they got the key to the city - and the place generally went bananas. It was the first and really only interview of this type I've ever done.

I was to meet him at his studio - I've been in plenty of studios - no big deal. I walked in there and whooa - this studio was a giant room with 48 tracks - literally ready to record the symphony! And I was about to interview Dick Wagner - the guy in the Alice Cooper movie I aw when I was 13. I'll admit to being a little nervous. But he was so cool, so easy, an hour and a half flew by and I got some good info. When we wrapped up [about 12:30pm on a sleepy Saturday] in walked Bobby Rigg, Donny Hartman and Tom Randall - the rest of The Frost! Believe it or not they gave me a private gig [also known as their rehearsal] which to be honest, was emotionally overwhelming. I unfortunately had to go and did not get to hear the whole rehearsal, but here's what I got out of the experience: Dick Wagner was a fuckin'A cool guy. They even let me record the music!

The Frost concert as I said above was amazing. But also, speaking of departed heroes, I'd be remiss if I did not mention that it turned out to be the last gig Cub did before he passed away. He was fantastic with the great Johnny Bee and Ray Goodman from SRC backing him up.

The web-zine tanked before it ever even debuted. I got permission to take my Wagner piece elsewhere and where better than here - where the real rock lives...

Only Fingers Bleed

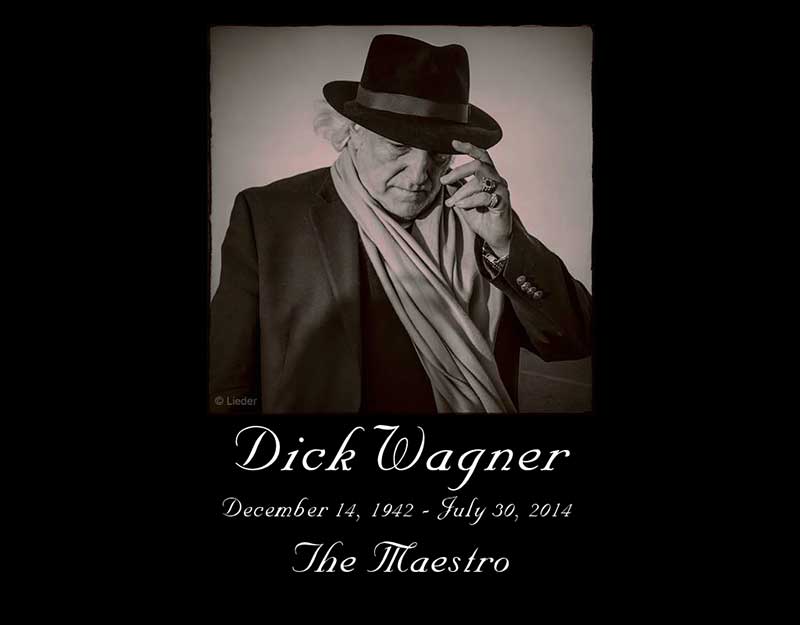

Even if you haven't have heard of him, the odds are that you've heard him. Guitarist Dick Wagner made a career for himself as a behind-the-scenes kind of guy, working with the likes of Alice Cooper and Lou Reed, not to mention Kiss, Aerosmith, Peter Gabriel, Meatloaf, Nils Lofgren, and yes, even Air Supply.

After starting out in one of the original DIY bands (they went from store to store around the state of Michigan selling their records), The Bossmen, in the mid-'60s, Wagner formed The Frost in 1967. The Frost was right in the middle of the incendiary Detroit rock scene that gave the world The Stooges, MC5, Bob Seger, and Grand Funk Railroad, to name but a few. The Frost was hugely popular in Michigan, but their extensive touring was for naught due to really bad distribution of their albums.

During a short stint in proto-melodic heavy metal power trio Ursa Major, Wagner hooked up with producer Bob Ezrin with whom he continues to work on occasion. It was this connection that led Wagner to play lead guitar on the classic Alice Cooper Group albums School's Out, Billion Dollar Babies, and Muscle Of Love.

When Lou Reed made his landmark album, Berlin, Wagner was called in to play guitar along with pal Steve Hunter (ex-Mitch Ryder, Chambers Brothers). The pairing of the two guitarists would last six years. Very few guitar duos ever have matched the skill, feeling, power, and compatibility of Wagner and Hunter. When it was time for Lou to take to the road, he had Wagner assemble the band and take care of the arrangements. The result was the live "Rock And Roll Animal", one of the greatest guitar records in existence. Combined with Reed's best songs (and that's saying a lot!), the fierce playing of the band led the album to (small c) classic rock status.

The Alice Cooper Group broke up in 1974 and the Hunter/Wagner Band was tapped to back Alice. Wagner essentially co-wrote the next four Alice Cooper studio albums (Welcome To My Nightmare, Goes To Hell, Lace & Whiskey, From The Inside) with Cooper and Ezrin. Welcome To My Nightmare, in particular, was huge, and a ballad Wagner originally penned in 1968 became "Only Women Bleed," a song that has sustained him financially over the years, as it has been covered by everyone from Etta James to Lita Ford, with about 20 other artists inbetween. The Nightmare tour was (at the time) rock's biggest tour ever, netting $9 million, an absolutely astounding figure for 1975. In '99 Rhino released an 81-track box set, The Life & Crimes Of Alice Cooper, and Wagner has 13 songs on it (plus two more that he signed away the rights to before the songs were even released).

Since moving back to his hometown, Saginaw, MI, in 1995 Wagner has reunited with his old buddies from the Frost for occasional gigs. The Frost played an amazingly well-received and well-attended homecoming show in Saginaw, and received several awards in 1999 and 2000, including the key to the city of Saginaw (the only one ever given away!), a lifetime achievement award from the Detroit Music Awards and a resolution from the Mich. House of Representatives thanking the Frost for all the band has done for Michigan R&R.

Wagner owns a truly spectacular 48 track digital studio (Downtown Digital) where he produces bands, and has a record label (WMG). There has even been talk of a Wagner/Hunter reunion project (musically along the lines of "R&R Animal"), but nothing has come of it yet. Wagner still takes his music career very seriously, but seems most concerned with developing new artists, helping them to avoid some of the pitfalls that he has faced in his career and, hopefully, getting them bumped up to another level.

Dick Wagner seems happy and healthy these days, and with his flowing silver hair, he looks a bit like Moses (Chuck Heston version). We got together in May 1999 and talked about the Frost and their reunion, Lou, Alice and the box set, and a bunch of other stuff. Wagner was easy going and forthright, and this is his story.

G: How and when did the Frost hook up?

D: I guess that would have been in late '66 or early '67. We really started out as Dick Wagner and The Bossmen, because The Bossmen had broken up, and I got together with Bobby Rigg and the Chevelles, and we formed what was eventually called The Frost. Originally we were called Dick Wagner & The Bossmen. Then I started adding all this material in and decided to change the name of the band to The Frost.

G: I guess (guitarist) Donny Hartman was in Rigg's band?

D: Yes he was.

G: What about Gordy Garris, the guy who plays bass on the albums?

D: The original member was Jack Smolinski; he was a bass player from Alpena, MI. He was playing with Bobby and Don. I just basically took the whole trio and jumped in with them. But, after a trip to New York to audition for Blood Sweat and Tears, I came back determined to make this band happen and to write original music, and I knew that I had to get rid of Smolinski. He just wasn't cutting it. And I remembered seeing Gordy Garris in another band, I forget the name now, and I called Gordy and asked him if he wanted to join up with me too. He said yes and there you go - we had The Frost.

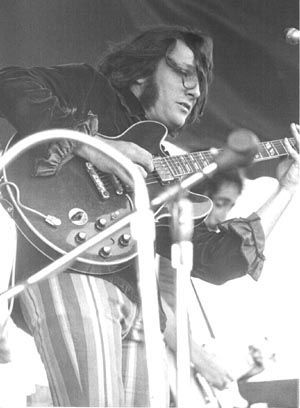

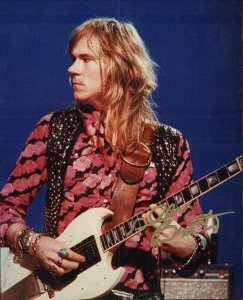

Dick with The Frost.

G: The Frost signed to Vanguard, which was known mostly as a folk label at the time. How did that happen?

D: Well, we were courted by two or three labels, but Vanguard had this guy Sam Charters flying in here every week from New York, and they were just like really putting the pressure on us, really wanting us to sign up, and really giving us the whole spiel, you know? And so we ended up going with Vanguard because of all the personal attention they gave us, thinking they were behind the whole thing. They were really gonna do a number all over the country for us. You know, we had a chance to sign with Columbia Records, which we should have done, obviously, but that's the way it goes. Columbia didn't send anyone out here, they were just calling me and talking about it. They wanted to make a deal with us, but we had Sam Charters coming in here every week, wining and dining us and doing the whole thing. So we decided to do that.

And really, when you stop to think, it was not a good move. We didn't have any management - I was basically managing the band and doing everything myself. I pride myself on having made some good decisions in my life, but that wasn't necessarily one of them, although Vanguard did sell a lot of records in Detroit. They knew we were going to sell records in Detroit, so they geared up for that. Other places in the country they didn't do any real promotion, but we sold 50,000 albums in the Detroit area in the first month. And I think, realistically, it was probably within the first week.

G: That's incredible!

D: Everyone went out and bought it. I mean, we were already famous and people loved us. And when the record came out, man, Bang! It was number 1 for months and months on the radio stations and the charts in Detroit. Vanguard had the foresight to see that we were popular and they actually pressed up the records and had them in stores. But when we toured, like when we played the Fillmore West in San Francisco, there were no records in the stores. So they didn't really follow us where we were going. We went to Frisco and L.A. and we played. We played all over Canada. We did a lot of playing where there were never any records.

G: Right, and that's a totally frustrating thing when you're a touring band, because that's why you're out there in the first place.

D: It made us crazy. You'd never find any records, DJ's didn't know who we were, but we used the same approach as I did in The Bossmen. We would go to radio stations and just go in and meet people. They would like us, you know, as people, because we were pretty nice guys, really, and then they'd take the time to take a listen. In those days DJ's were still actually listening to records, and we'd get stuff on the air. Maybe it was one spin, maybe one hundred, I don't know. We were basically trying to do everything ourselves—booking our own tours. We were tied up with Vanguard which wasn't really distributing the records the way we wanted them to, although we were selling the records here in Michigan.

G: And this was the "Frost Music" album?

G: And this was the "Frost Music" album?

D: This was "Frost Music", the first record, yeah. Then they came in and recorded us live at the Grande Ballroom, when we did the second album (Rock & Roll Music) which was half live/half studio. And you know, "Rock & Roll Music," the song, turned out to be kind of an anthem for us. It was a real big song for us. And, as a matter of fact, Vanguard did a good job for us in France, because it was the number 1 song of 1969 there. But we never toured Europe. We had no contacts for booking and stuff. So here we were, stuck, kind of doing this Mid-western thing. We were going to New England and Canada and knocking people dead at our shows, and there was hardly ever records for sale. It became kind of frustrating for us, you know?

G: You would have sold more records if you did it like The Bossmen, and took them around and sold them yourself.

D: We certainly would have, yeah.

G: 'Cause you would have sold tons at the gigs.

D: We should have been doing what people do today: Sell 'em out of the trunk of the car, you know what I mean?

G: Exactly—and that way you keep the 10 bucks rather than getting about one dollar.

D Right, you keep the $10. Exactly right. So The Frost ran its course. We were together maybe three-an-a-half years. Then this guy came in from New York City, a potential manager for the band, and I wanted to work with the guy.

G: What was his name?

D: Dennis Arfa. He owns the QBQ booking agency in New York now. He's Billy Joel's agent, and The Beach Boys, and Rodney Dangerfield. He's a big-time agent. And he came in and became a friend of mine. He wanted to manage the band, and the rest of the guys didn't really like him. He was very "New York," and a bit of a wheeler-dealer. He was a young guy, 21 or 22. I liked him. We got along really well. And he wanted me to come out to New York.

So, The Frost split up and I went to New York. The first thing I did out there was do some rehearsals with Billy Joel and some other guys. We were going to form a band together. Billy ended up having some problems, couldn't do it, or whatever. So I'm stuck in NYC. Just me and a drummer. So I got a hold of Greg Arama, from the Amboy Dukes. Arama came out to New York, and that trio - we started rehearsing.

G: That was Ursa Major?

D: Yes. We made one record for RCA, and the Billy Joel thing went by the wayside. Billy went to California and became a star. But it kind-of started there. Dennis was acting as manager for all us people. So after Ursa Major came out on RCA, we opened about 20 dates for Alice Cooper on tour.

G: Aha!

D: And we opened about 20 dates for Beck, Bogert, and Appice. Jeff Beck. That was the extent of our playing. We did do a few club dates as well, like down in Florida. We came home to Michigan and played a bit. Matter of fact, the last date Ursa Major did was in Pontiac, MI. And we got stuck there - they had like 20 inches of snow in one night. We were stuck in a motel for three days, fighting with each other all the time. We decided to break up the band, and that was that. When you get to Michigan with twenty inches of snow, and you just came from Florida, and you're already pissed off at one-another anyway, it's like AWUUGH! No more! I can't take this anymore! But it was a great trio. I mean, Greg Arama was an amazing bass player, and Rick Mangone was a great drummer, so the potential was there. And the dates we actually played, 40 to 50 dates total, we killed.

G: I've always liked the Ursa Major record.

D: I think it's kind of a classic, in a way. It's one of the first records to really be a heavy metal album with melody. It was also my first association with Bob Ezrin.

G: Yeah, that's another thing I certainly want to get into, but before we get to far ahead of ourselves, I want to ask about the Detroit rock scene in the late-60's and early-70s. Creatively and energy wise that scene was definitely one of the high water marks of the rock-era. You had The Stooges, MC5, The Rationals -

D: Question Mark, SRC, Savage Grace.

G: So did The Frost play a lot of gigs with all those bands at The Grande Ballroom?

D: Yeah, there were a lot of times that we would play places together in different combinations, and there were some big festivals like Saugatuck Pop Festival, and there was a big one at Detroit Fairgrounds. A lot of the bands played at Goose Lake, which was for about 200,000 people. The thing is, you could get five or six of those local bands together and draw 25,000 people. It was always fun. And in those days there were enough places to play that you could play seven nights a week. I mean, you could be out all over the state. And The Frost, every time a new place would open, basically the first opening night was with The Frost, because we were guaranteed to draw a huge crowd. Always. And so we held attendance records everywhere--all over the state for a long, long time until Bob Seger and Ted Nugent got real, real big. But then we were like the top band around, you know.

G: Yeah, that sounds pretty cool.

D: And it was real cool. But, there were so many great bands, and they were all different, and all interesting in their own way, but they all had that Detroit, you know, heavy guitar attitude...

G: Right. The attitude.

D: You know, that sound was born out of the industrial Mid-west.

G: Why Detroit? Why not New York, LA, or Florida? Why was it in Detroit and the surrounding Michigan area that there was so much high-energy rock and roll?

D: Well, you hear enough of those General Motors, Ford, and Chrysler factories goin' in your life, and you want to play your guitar loud. You have to compete with the background.

G: Like early industrial music, huh?

D: Yeah, kind of, y'know. I think heavy metal was more or less born here, as far as in America. Although the Detroit scene had a bad rap nationally - that we were all just "loud bands," if you take a look at some of the music that came out of that era, that's not true. Sure we were all loud, but there was some really great music there. There was such excitement at the live shows, and the audiences were totally into it, so as a vehicle for expression, during that time, in that scene, it was just happening. It was absolutely great. And when The Frost went to San Francisco, which was very hippie-dippie, you know, we went to the Fillmore and played for three days opening for BB King. You wouldn't picture The Frost and BB King, and what happened was, we completely destroyed the place. And of course BB King is BB King, so he always destroys the place. It ended up with me and BB King jamming and it was just really cool.

G: Yeah, that must have been pretty thrilling for you as a young guitarist.

D: So The Frost, we were out of our element, in a way, with the kind of music that we played. But even there, in San Francisco, people just absolutely loved it. And when we went down to L.A., the same thing happened there. They'd never heard our music before and they loved it. I remember the first time The Frost played as "The Frost" on a big date in Detroit. We played Meadowbrook--it was some kind of festival.

There was about 15,000 people there, and it was the first time we'd been exposed to a "Detroit" audience. The headliners were the MC5 and the Stooges, and all these other bands, and The Frost was this new band in town. We came on in the middle of the afternoon, all dressed in black and looking cool, and just did our thing, and the audience went absolutely nuts. That was the beginning of our reputation as being this great, mysterious kind of band. From there on it just kind of snowballed. It was automatic. My phone rang off the hook, y'know? People wanted to book The Frost. Those were great days, and radio was exciting in Detroit. Our album was number-one for like four months straight, and we got knocked off by Led Zeppelin.

G: Well, you certainly can't feel to bad about that! I'm sure you're not alone - Zep must've knocked a few others off as well.

D: But that whole scene was absolutely great. There are still remnants of people from that scene that still play today. You know, myself and The Frost have done some dates. And then there's Cub Coda (RIP) who did the show with us here in Saginaw. But there's a lot of great players that came out of that era. Bob Seger, especially. And he succeeded more or less by staying in Detroit and playing and playing and building the audience even bigger, until he was selling out the Silverdome [a 70,000-seat football stadium] as a local band. Bob Seger is one of the great talents, no doubt. He's not singing much anymore, I don't know exactly why.

G: I heard he got like $50 million for letting Chevy use "Like A Rock."

D: Oh, he got a tremendous amount of money for that. And that has really helped Chevrolet. Whoever had the idea to combine the two - that was pure genius. Bob doesn't need to make the money. He's got the money. He always loved performing, so I don't know exactly why he doesn't go out and tour anymore. But whatever, you know. Maybe he's content.

G: Maybe he's got the family thing going on.

D: Maybe he has one of those little money counters, and he just puts the dollars through and counts.

G: So how did you hook up with Bob Ezrin? Was it from playing with Alice Cooper? Opening for them when you were in Ursa Major? In fact, didn't Ezrin produce the Ursa Major record?

D: He produced Ursa Major, and I'm trying to remember if we were working on that before I played on School's Out.

G: You and Ezrin used to be like a team.

D: Yeah, we've had a relationship for a long, long time. Ezrin was a disciplinarian with those guys [the Alice Cooper Group]. He made them practice, he made them play right, and he made them be better. In some cases he brought in other musicians to do what they couldn't do, so he asked me to play guitar on School's Out as a session player.

G: Because Glen Buxton [R.I.P.] was too wasted?

G: Because Glen Buxton [R.I.P.] was too wasted?

D: Yeah, he was wasted. He couldn't really do, y'know, stuff. So I played stuff on that. I remember being out on Long Island, rehearsing Ursa Major. We had just gotten this deal with RCA, and Dennis Arfa, our manager, said, "There's a guy who wants to see you. He's a producer, Bob Ezrin." And Bob came walking in, this 21-year-old kid with hair down to his ass. I said, "Who's this punk? What's he think he's gonna do with our music?" So, he was real cool. We got along. We were of the same mind as far as how records ought to be made, you know? And he worked out great. So that's when I first met Ezrin. And then, I think this is right after that, we were in the studio with him, and they were doing the Alice Cooper record at the same time. And they asked me to play on the Alice Cooper album.

G: So Buxton was pretty wasted. Did he even know he wasn't playing this stuff?

D: I don't think he really knew. It's hard to say for sure. He was never in the studio. I used to go up to the mansion in Greenwich, and he'd be there, but he'd usually be upstairs in his room. You know, he'd be isolated and then he'd come down once-in-a-while and just poke his head around. He was never really into it. And when they toured, they had other guitar players doing it too.

G: Why didn't they quietly just bring you in and phase Glen out? Was it for image purposes?

D: Well, it was a known entity at that time; it was the Alice Cooper Group. And I think they felt loyal to him, they had all grown up together, and it would be hard to just get rid of someone who was there from the very inception.

G: At one point he was a REALLY good guitar player.

D: Yes he was, yes he was. But he got brain damaged, you know? But then later on, Alice's manager, Shep Gordon, asked me to help him put together a new band. You know for Alice. And Alice really liked my writing. We had written together, me him and Ezrin. We wrote "I Love The Dead," which was the big thematic song at the end of Billion Dollar Babies tour. So I'd done some writing with him, and he liked writing with me, and asked me if I'd help put a band together and be his co-writer.

G: Before we get to that, I want to ask you about Lou Reed and the "Rock And Roll Animal" deal. I think a lot of people, myself included, look back on that as one of the truly great guitar records ever made. The playing is all the way out there, the guitar tones are so sweet, and the songs are among the best ever written.

D: Lou's a great songwriter.

Dick and Lou on the Rock and Roll Animal Tour.

Dick and Lou on the Rock and Roll Animal Tour.

G: Yeah, you take "Sweet Jane," "Heroin," "White Light/White Heat," and "Rock and Roll," and you've got four of the best rock songs ever written.

D: Yeah, they are.

G: And then you guys took those songs to a whole other level. Who did the arrangements on that tour?

D: Most of the arranging was mine, yeah. I was more or less the leader of the band, and the guy who did the arrangements, although that intro to "Sweet Jane" is Steve Hunter's. He had already written that as a composition, and we just tagged it on the front of "Sweet Jane," because that was a really cool thing and it fit together perfectly.

G: Yeah, it certainly worked.

D: Of course, that's sort of a classic thing.

G: Actually, my former editor thinks the "Sweet Jane" intro, just in terms of guitar playing is one of his favorite things of all time.

D: A lot of people say that, and I agree with it. It's very, very cool.

G: But also, the twin rhythm guitars in "Rock And Roll" are just beautiful, and so exciting.

D: I think that Steve Hunter and I were like - what's a good word for it without sounding too egotistical?

D: I think we were the best example of two rock-and-roll guitars playing together since Eric Clapton and Duane Allman in Derek & The Dominos. Although it was a different style of music, we just had that intensity. And Steve and I have been that way from the very beginning. Steve was playing with Detroit (the band) with Mitch Ryder, and I was in Ursa Major, and we were playing in Ft. Lauderdale at a club. Steve Hunter was in town with the Chambers Brothers, and came out to the club one night with the Chambers Brothers. We talked a little bit and I said, "Well, come up and jam, you know?" And this was with Ursa Major.

We played for like two hours, man, and it was like, "Wow." It was just there. We could feed off each other, and knew when to let each other play. It was just great. Bob Ezrin was going to produce the Lou Reed album, and he'd already worked with Steve and me--on the Mitch Ryder record and Ursa Major. So he thought we'd be a pretty good combination. We already knew it would be. So we got together and played on the "Berlin" album.

G: "Berlin" is definitely a landmark album in rock history.

D: I think it is a landmark. As far as songwriting goes, it absolutely is. It's a spellbinding album. It didn't do well because it was not "up" enough. It's a very depressing album.

G: As a follow up to "Transformer", which is such a nice little record, it was like, the most depressing album ever made.

D: Just phenomenally dark.

G: So it was a commercial disaster, but 25 years later, looking back, it might have been the best thing Lou ever did.

D: I think it is. Just the whole concept of "Berlin," and that opening little thing with the piano and the 1930's sound. It's a brilliant album.

G: Didn't working on that cook Ezrin completely?

D: Yeah, he got pretty cooked on that one. That was quite an artistic tour de force for him, and for Lou, and for all of us, really. We believed so much in it, because it was so artistically beautiful and wonderful. And this was going to be, like, "the Sgt. Pepper's of the 70's." And it didn't happen. And that was such a disappointing thing to us, because we put so much into it. It was such a beautiful piece of work. Anyway, that's when Steve and I started our association. Then Lou wanted to play live, to go to Europe etc. So Steve and I got together with him, and Whitey Glan (drums), Prakash John (bass), and Ray Colcord on keyboards. And we formed the "Lou Reed Rock And Roll Animal Band."

From the first note, I remember the first rehearsal, when that band played: "Oh, what a band!" It was just immediate. At that very first rehearsal I said to those guys--this was before Lou came in to sing, we were just playing, "You know, we're going to do this thing with Lou, but at some point, this band needs to make a record." I said, "this is just too good." So we put that together, rehearsed for two weeks, and we went Europe and did a tour. And the band just absolutely killed everyone. All the reviews in the magazines and stuff were about me and Steve Hunter, really. Kind-of negative about Lou. He was pretty "out there" at that time, but you know, Lou was the genius of the songs anyway. He should've gotten more recognition, but it's interesting how the press dealt with it. How they really built up the band.

G: One of the big raps against Lou prior to that tour was that the band he toured with in 1972, The Tots, were sub-par. When you listen to that stuff now, it was actually pretty good, but they weren't near the level of the R&R Animal Band. And when he hooked up with you guys...probably anyone who was paying attention before was like, "WHOA!!! I certainly wasn't expecting this!"

D: Yeah, 'cause that band was amazing live, just amazing.

G: There are two albums from the tour, "Rock And Roll Animal" and "Lou Reed Live", which are basically the same show?

D: It's the same show.

G: How much of it is actually "live"?

D: It's all live, all of it.

G: So what did (producer) Steve Katz do to get his name on the record?

D: He didn't do anything. He just sat there.

G: That's what I figured.

D: That's what the band sounded like. That's just it. That was just live, a pure live record. Which really shows you how great the band was. Because that's without doctoring it and tailoring it, and it's still just incredible.

G: And you know, one of the really bizarre things that I don't think people realize is that Animal was made on the tour for Berlin, and those records are about as different as any two albums Reed has ever made (OK, "Metal Machine Music" was slightly out there, too). You've got the somber orchestral vibe on the one hand and the screaming two-guitar thing on the other. Were people surprised by that? Were folks expecting some kind of recreation of "Berlin" when they got "Rock And Roll Animal"?

G: And you know, one of the really bizarre things that I don't think people realize is that Animal was made on the tour for Berlin, and those records are about as different as any two albums Reed has ever made (OK, "Metal Machine Music" was slightly out there, too). You've got the somber orchestral vibe on the one hand and the screaming two-guitar thing on the other. Were people surprised by that? Were folks expecting some kind of recreation of "Berlin" when they got "Rock And Roll Animal"?

D: I don't think so, because I don't think most people were actually that aware of "Berlin" in the first place. A lot of the songs we did, of course, on the "Rock and Roll Animal" tour were from the "Berlin" album. Only they were the band's versions, if you know what I mean.

G: What was it like working with Reed during his "extreme behavior" phase?

D: Lou's a great songwriter, but an enigmatic character. We got along very well, but I suspect he thought I was a little bit too "normal," as a person.

G: Now, on to the Cooper years. First off, what do you think of the just released box set, "The Life And Crimes Of Alice Cooper"?

D: Well, having just looked at it, I think it's a beautiful package, I think it's really well done. It's phenomenal, really. It's so cool. And the book inside, I mean I haven't read everything, but I was glancing through it all, you know, and it's quite a statement about Alice Cooper as a superstar. I think it's really the kind of notice that he's deserved for a long time. And the selection of songs, just checking over the titles, I think it's a great chronology of what he started out as, how he ended up, and how he got there. I think it's a great collection of songs. And of course I'm very thankful to have 13 songs of mine on there. Actually I wrote a couple of other ones too, but I'm not credited. "I Love The Dead," and "Escape." I wrote the melody to that song, but they asked me not to be on the song because there were already four other writers.

Alice and Dick.

G: I guess Kim Fowley was one of them?

D: Yeah, and to be honest, I don't remember these people even having anything to do with it, but they know. It's alright. I was there, I was making a lot of money, had a lot of songs on the record (Welcome To My Nightmare), and I really didn't care. And they asked me to please sell my rights, because other writers, like Fowley and Mark Anthony, didn't want to be part of a song that had that many writers on it. I guess they didn't care who wrote the damn melody, but then again, whatever! It's one of those things. It'd be nice to have more royalties, you know, but I've made money off these songs and continued to do so, so I don't have any sour grapes, really. It's not a big deal to me.

"Escape" is not the greatest song in the world. If it were "Only Women Bleed," I'd be fighting, of course. [Joint laughter.] I feel like I should fight for "I Love The Dead," but I did make a deal with them at the time. I sold my rights to the song. You know, because they caught me at a time when I really needed money, and they gave me some. Not as much as I would have made over the years, but it was a bird in the hand. So I sold my rights to the song, and it came out as being written by Alice and Bob Ezrin. But the truth is that I'm one of the primary writers of that song.

G: Tell me about "Only Women Bleed." Has it really been covered by over 20 artists? Did Etta James really record it?

D: Yeah, that was totally cool. There's been a lot of people who have covered it. Tina Turner, Carmen McRae, Mary Travers and Lita Ford, to name a few.

G: It's interesting that it's been covered mostly by female artists.

D: Actually John Farnham had a hit with it in Australia a few years ago.

G: There's a song on the box that you will definitely want to listen to called, "For Britain Only."

D: "For Britain Only," no, I don't know that one.

G: It says on the box that it was just released in England as a single, after Alice went over there, sort of "Special Forces" era. And people actually cared, which I guess meant a lot to him at that point. So he wrote this song "For Britain Only." In the middle of the tune there is an excerpt from "Guilty." Maybe two or three seconds worth.

D: Really? Well that's cool.

G: Call your lawyer, man.

D: Yeah man, if they use enough of it, I will. [more laughter]

G: I mean, it's pretty minor, but since the exclusion of "Guilty," (from "Alice Cooper Goes To Hell") is one of my few complaints about the programming of the box, at least they fit it in there somehow, you know? What was it like working with the old Alice Cooper Group, I mean the guys in the band rather than Alice himself, who you worked with for many years after that?

D: I didn't really have a lot of involvement with them. They would have tracks cut, and I'd come in and basically do overdubs. But I knew the guys, and you know, hung out with them a bit in Connecticut, at the mansion, and I really liked those guys. We got along fine. I think they saw me as sort of an interloper, but on the other hand, there I was.

G: I guess my first exposure to you and your music was the "Welcome To My Nightmare" movie as a 14-year-old: that guitar duel scene.

D: Right, with the spiders going up the net!

G: Forget the spiders - it was the guitars that got me. And, that totally holds up.

D: I think so, too. You know, the Nightmare tour was so innovative theatrically, and it was also the biggest rock and roll tour of all time, at that point.

G: In terms of trucks and gear and...

D: And in dollars made, and the whole thing. That was a $9 million tour. Nobody had ever made nine million before on tour before that. And now they make a hundred million so...well at least some people do.

G: I heard the Eagles are doing a New Years Eve [2000] show at a 20,000 seat arena –- ticket price $1,500.

D: You're not serious? How do they have the nerve to do that? I mean, you know, wow!

G: They're looking at a $10,000,000 payday for one night.

D: That's a hell of a New Year's Eve paycheck. I'll tell you what. You know, money is nice, but my God! I guess if people will pay it it's alright to do. I don't know. We live in a capitalist society, and that's supposed to be OK, but it would take a lot of nerve to say, "How much am I going to charge for tickets to this show? Ah, 15 hundred dollars, that sounds good. We charged a hundred on the last tour. Let's charge 15 hundred and see what they do."

G: Back to Nightmare... How many tours had a movie at that point?

D: Right. Well you know Alice was at the forefront of a lot of things. Especially in theatrics in rock and roll music. He really started the trend, opened up the door for everyone. I think he's under-acknowledged for that.

G: At this point his legacy is basically as shock-rock king. The guy with a snake who paved the way for Marilyn Manson.

D: It's so much more than that, and it's so much more classy. And if you actually listen to the Alice Cooper albums, you hear a lot of really great music in there, stuff that a lot of people have never actually listened to.

G: Regarding the recent tragic school shooting at Columbine, Marilyn Manson is catching a ton of hell (no pun intended) for corrupting the nation's youth.

D: Yes, I see that.

G: Back in the day, Alice Cooper was catching the same kind of hell - everywhere he went there were protests, city councils were passing legislation to ban Alice from their towns. Are there any parallels to be drawn between Cooper and Manson? Is Manson more hateful than Alice and therefore more deserving of the criticism?

D: Well, I think there's no doubt that he's a lot more hateful. I don't think Alice was ever hateful. I mean, the things he did about violence and so on weren't all caricatures, but they were definitely "anti-" in their message. I think Marilyn Manson's message is much more "pro-." And Manson, thrown in the middle of the era of gangsta rap and stuff, I mean, what you have is just a complete change in the culture. You've got, you know, people who really just want to hear that stuff because they want negativity. They feed on it.

G: I think that's mainstream society at this point.

D: Yeah, they feed on it. It's amazing to me. I could just never understand it. I took in my nephew when he was 17. When I lived in Nashville, he was getting into a lot of trouble down in Florida. His dad asked me if I would take him in, so he lived with me at my house, you know. All he listened to was gangsta rap. All he would talk about was how cool it was to go to prison. You know, how cool it would be to be one of those guys. Now he's in prison for like six years, and I don't think he thinks it's so cool now that he's actually there. But, I mean, just feeding on it. When I took a listen to what he was listening to, I couldn't believe it. It was like, I knew rap music was "out there," but I had no idea how really violent some of this stuff is. And God, it just amazed me. Why the culture has made such a shift? I don't know.

I think it started with that group in Florida, 2 Live Crew, and their whole deal with the girls, you know, sucking their dicks on stage. And it was like a novelty, and you could almost see it in a way if it's a novelty and it's the first time something like that has happened. But that sort of opened the floodgates, I think. And then it became more than a curiosity, it became something kids could be rebellious with. And today, God knows what's in these kids' minds.

G: So when you were touring with Alice in the '70's, was he still catching a lot of that stuff, or had the Muppets thing sort of tempered it? [Alice appeared on the Muppets TV show]

D: Oh, I think Alice's whole thing got tempered there, you know, when he started playing golf with President Ford. I mean, it kind of took the edge off anything people might have thought about him as being violent. Alice was on television saying, "Well, it's just a character I developed." And probably for his career, it was a bad thing to allow that to happen. He should have kept his underground mystique going.

G: Oh, absolutely. That was the thing. Once you've built up an audience with that kind of persona, then going Muppets, you're bound to lose a lot of that base. The good news is that he continued to make some good music. But I guess those albums, each one sold a little less than the one before it.

D: Yeah, they did start dropping off, because the image was kind of spoiled in a way. But people still enjoyed seeing it live, as a live show, because it was still really theatrical. Whether the message was exactly the same or not, didn't really matter. People wanted to come see that show. But I think it's a choice that Alice had to make, in a sense, because he's really a guy who's got his family, goes to church, and plays golf. Aside from the fact that he's able to think of and create this bizarre stuff, he's not really that person. And that's what he was trying to say, that he didn't want to have his entire life, everything about him, thought of as that character.

G: Back to the music...In the song "Wish You Were Here," from Alice Cooper Goes To Hell, there's one part of the song that was taken from the Ursa Major song, "Stage Door Queen," which is definitely one of your greatest riffs. You had the whole drum part and everything in the arrangement on there. Were you thinking, "That's so good, I've just gotta use it somewhere" ?

D: Bob Ezrin and I were talking. We decided we wanted to use it because we loved it on Ursa Major, and Ursa Major hadn't been a hit record. So we thought we'd put it in and see how many people would actually recognize it. And you're one of them. You know, how many people would actually say, "I heard that before from Ursa Major." So it was kind of just for the fun of it. But it fit. It worked. I have a tape here somewhere of the songwriting sessions that Alice and I did in Hawaii for the Goes To Hell album. I guess I should've given them that for the box set. They're mostly just the process of writing, but I actually have sort of a finished demo, just acoustic guitar and me and Alice singing. It was done at Cherokee Studios in L.A., just before the record was made. It was basically us putting them down in the studio to let Ezrin hear them.

G: Of the records that are represented on the box, AC Goes To Hell seems to have gotten the short shrift. There are only two songs from it, "Go To Hell," and "I Never Cry." If you added "Guilty" and "Wish You Were Here," you've basically got the whole story in there. All four of those songs deserve to be on the box.

D: Yeah, I think so too. "Guilty" is cool. If I went down the list I could pick out some other songs to put in there, too. But I'm glad they used "I Love America," because that song is hilarious.

G: We were listening to the box set in the office the other day and "I Love America" had us rolling on the floor laughing. It's so goofy.

D: I love that song. I think I'm going to perform it with my band. I just think it's a funny tune and a cool song for the summer. [Sings] "I Love A-mer-ica". Have you ever heard the "Dada" album?

G: Actually no, not in its entirety. It's impossible to find now.

D: If you wanna hear a really hilarious song, listen to "No Man's Land." You gotta check out "No Man's Land"! That should be on this record too. There's some stuff [on "Dada"] that is totally obscure and really cool. Dada's a great record, I think. The songs are really weird, and really good. We had a lot of fun writing that record.

G: Did that sell at all, or was it too....

D: No, it was a complete failure. It just didn't sell AT ALL. It was the last record he did for Warner Brothers.

G: So what was Alice's state of mind like around then, when he'd had several major flops in a row, really?

D: He was completely depressed, drunk. It was a really bizarre scene. But we actually had fun because we were in Toronto and were staying at this hotel, and we'd go down to the bar every night and play piano all night, singing songs for all these people who were hanging out at the bar, and everybody was lovin' it. We were having a good time, you know? And we wrote a lot of really great songs. They're some of the best songs from the whole Cooper history, I think. It's really interesting stuff. One of those is on the box, "Formerly Warmer." The idea was Formerly Warner's, like Formerly Warner Brothers.

G: I was listening to "How You Gonna See Me Now" (off "From The Inside"), and even though Bernie Taupin co-wrote the whole album with you guys, I was surprised to hear a song that actually sounded like Elton John. I was like, "Whooooaa Baby! What's going on?"

D: Yeah, I think "From The Inside" is a fine record, worth going back and listening to.

G: Let me ask you a couple of technical questions. What set-ups did you and Steve Hunter use back in the day?

D: We were both playing Les Paul Special guitars. Steve's was a TV model, and mine was just a regular Les Paul Special. We played through Marshall stacks, with an MXR phase-90 phaser, and an echoplex. You know, a tape loop echoplex. Real basic.

G: Yeah, the tone on those guitars is so sweet. I guess only a Les Paul is going to get you that kind of tone.

D: The Les Paul and the Marshall together, when it goes through that echoplex, for some reason it just smoothes it out and makes it really nice. It's just basic, fundamental guitar playing. That's my philosophy anyway, and I think Steve's the same way. You try to get as close to the natural sound of the guitar as you can. All this processing that's going on today--a lot of the stuff is not that good. A lot of the new processing is good, too--on record. But live you hear some people and it just sounds all washed out.

So if you can have that fundamental, great guitar tone, you're way ahead of the game. When you get that fundamental tone, it's harder to play, because you have to actually be able to play, really play, and you can't do things that are just slop that get dissolved into noise, and make it sound like it was something cool. You can't get away with that. You've got to actually play notes.

G: How has your playing changed over the years, and what is a Dick Wagner guitar solo all about?

D: My playing has gotten better, technically as well as musically. I've learned how to edit myself and play with a concise sense of structure, as opposed to throwing in the whole book of knowledge on each song. My solos are about supporting and elevating the song, and providing a release for the listener.

G: By the way, what ever happened to the guitar hero? At one time that was the most highly valued thing in rock. Now it's barely a consideration.

D: Well, as far as young people today, the whole thing has changed. It's a different kind of focus. It's more on the kind of songs, and the image of the lead singer, and the image of the band. As opposed to whether or not they are actually great musicians. The kids don't really care. From grunge on up, nobody really cared if anybody could play or not. That's bound to change, and bound to go through phases, because eventually people have to come around to wanting to hear good musicianship. You know, as you get older, you just start to reach that point where you want to know if these people can actually play. It's not enough to just pound you over the head.

G: A great song is a great song. But when it's really played well, all the better.

D: I think what you are saying is true, but I wonder if that's more of a concern with records than with live playing. I wonder if live, people can still appreciate a great guitar player. I think they can; otherwise Stevie Ray Vaughn would never have made it. When you stop and think about it, he's not a likely candidate, because he's a guitar player, to become a big star. But because he was a great player, he did become a star. So he's one of the guitar heroes, and an example of how a musician can break through.

G: Did you and Hunter play on each other's solo albums that came out in the '70's, the Richard Wagner album, and Hunter's '"Swept Away"?

D: Steve played a little bit of rhythm guitar on mine. I did not play on his records. I wasn't around when he was recording it in California.

G: Had you moved to New York? Is that the deal?

D: I was living in Connecticut, yeah.

G: The 'burbs?

D: Yeah, the 'burbs.

G: So throughout the late '70 and early '80's, Ezrin was really hot. I guess it was like 1975 when you worked on the Kiss album, "Destroyer"?

D: I did the "Destroyer" album, whenever that came out.

G: It came out in '76.

D: That's around the same time we were doing the Nightmare stuff. Yeah.

G: I read some stuff where members of Kiss acknowledged that Ezrin was really instrumental in that album sounding the way it did and being as good as it was. I guess some of those classic Ace Frehley guitar solos I grew up with were really you, huh?

D: Yeah, some of them were.

G: BOY, IS ACE FREHLEY GREAT!!!!! [mutual hysterical laughter]

D: Well, he's a good player, but Bob used to call me or Steve in for different projects. Usually depending on who was closest to where the sessions were going on. We would play, I don't know why, exactly. It's not that these bands couldn't play. Like Aerosmith: We did the "Get Your Wings" album, with "Train Kept A Rollin'." All those basic guitar tracks are Joe Perry and Brad Whitford, but when it came to the solos, it was Hunter and me. You know - Bob liked the way we played...

G: Interesting. I didn't know Ezrin did the "Get Your Wings" album.

D: Well, Jack Douglas produced it, but he was kind-of working for Bob. Bob was like, the big guy on all these.

G: Right. Douglas had been involved with most of the Alice Cooper albums.

D: Bob was overseeing all that stuff, you know, so he had Jack Douglas call us up. Bob was instrumental in an awful lot of stuff that I did.

G: So I guess you got a lot of session work over the years because he was producing all these hot bands.

D: Yeah, he'd call us in to play. Me or Steve. We both got a lot of work through Bob, which helped us, of course. I think we also helped Bob, because we had a sound, and a way of playing, and a way of understanding the stuff, and it just worked.

G: I guess it was around '85 that you played the Guitar Army benefit show for Vietnam Veterans [featuring, among others, Mitch Ryder AND The Detroit Wheels, Mark Farner from Grand Funk, MC5 singer Rob Tyner, Scott Morgan, and Dick Wagner & Donny Hartman]. I have a tape of that.

D: You do? Really? Is it good?

G: Is it good? It's outrageous!!

D: Really?

G: The first time I heard it I was stunned by how good it was. The version of "Rock And Roll Music" is fantastic. And "Motor City Showdown," from the Richard Wagner album is, like, ten times heavier than the original. It blew me away, the whole sledgehammer effect of it all. How did that show come together, and how did you get involved with it?

D: I think it was through Doug Podell. He's the program director at WRIF, in Detroit. He was at WLLZ (Wheels) at the time. I can't remember how I got invited to do it, but I think it was through Doug Podell. He put that thing together. They just asked us to do it and we wanted to help the Vietnam veterans. They had musicians available to back us up, so we went down there and just kind-of did it.

G: Was that the first time you'd played with Donny Hartman since the Frost?

D: Well, you know, over the years, even after Frost broke up, a couple of times a year I would travel from wherever I lived to Alpena [Michigan], and sit in with those guys. Bobby [Rigg] and Donny kept playing together in a band up there, you know, playing little clubs up North. [That's Northern Michigan for all you southern hemisphere readers.] So I'd go up and just sit in with them and spend a couple of days visiting my friends. And we'd play. So it isn't like we never, ever played together. That was just for fun, you know?

G: It sounds like fun.

D: Yeah, it was a kick.

G: 'Cause you're used to the whole L.A.-New York vibe...

D: Yeah, and all of a sudden I walk into Alpena and I'm a hero. Dick Wagner's here, yeah! It was a good ego boost, you know? It was real nice. No blase attitudes in Alpena.

G: Right. They were psyched to be seeing something REAL.

D: They were psyched. And I'd get on stage with these guys, and we did a lot of cover tunes, and a lot of good old rock and roll things, from Creedence to blues to whatever. So it gave me a chance to sit in with them and play songs that I normally didn't play. I'm used to playing my own music. Whenever I have bands I'm always playing something that's mine, unless I'm with Lou or Alice. And with Alice it's still my music. Most of the stuff we did live on the tours, a lot of it anyway, was my music. And I used to write all the segues. Like on the Nightmare Tour, we had some musical segues between songs. I wrote all that stuff.

G: I was looking at my old Alice Cooper records and you can sort of see the point where you're not playing on them anymore - there are some really bad records there.

D: That was right after "From The Inside". He started doing all this trash, I don't know why.

G: Yeah. And then I was surprised to see on one of the later really bad records, there you were again!!!!

D: Well, you know, we had a parting of the ways. Alice and I have always been friends, but his management and I kind of had a parting of the ways. So I left. During those years he did, like, three albums with this sort-of punk attitude and all that stuff. And I don't think they were such great records. But then they called me and asked me to come back and write with them again. And he and I wrote a record called "Zipper Catches Skin". [Geoff winces] That was during a very bad time for both of us, which I'd rather not go into. So it was a very neurotic record. And then we did "Dada", which as I said, has a lot of really creative stuff on it. We did that in Toronto, with Bob. I also wrote a song with him called "Might As Well Be On Mars," which is on the "Hey Stoopid" album from a few years ago. So I've done a little bit of work with him over the years. But it's never been like it was back then, when we were together every day.

G: Do you guys stay in touch?

D: Oh yeah. I saw him at Pine Knob [a summer music shed outside Detroit] last summer, and we talked about writing. He wants me to write with him on a new album. And he's promised to come up here and write in my studio, but he said he wouldn't come in the winter. So I'm hoping to get him up here in the summer. I don't know whether it will actually happen or not – Cooper's busy. He's down there in Phoenix. He's got a mansion, he's got family, he's got a restaurant, and he plays golf every day. So whether he'll actually get away and come up here, I don't know.

G: Why wouldn't he want to come to Michigan during the dead of winter, then?

D: Yeah, why would you want to be down in Arizona where it's hot, right?

G: He should be up here shoveling snow! So when did you move back to Saginaw, anyway?

D: I came back four years ago.

G: And what was it like coming home, so to speak?

D: Well, it was pretty cool. I found out that I have an awful lot of friends and fans here. I was living in Nashville; I'd been living there about three years and I was having a hard time. I moved from L.A. to Nashville because I thought Nashville was a really great songwriter's town, where I could really get some songs covered. What I found out was that if you're from the North and you played with Alice Cooper for years, they don't give a shit what you've done, and they don't even want to hear anything. They just give you that "Nashville Smile," and they're really nice to you, but they don't care and they don't listen. So I had a hard time in Nashville making things work the way I wanted them to.

In my heart what I always wanted to do was to have my own recording studio and be able to make records, make my own records and all of this. That was not going to happen in Nashville. Besides, there's too much competition there anyway. Too many studios and too many musicians. So I started coming back to Michigan to play a little bit. Play some live dates. I realized from the very beginning, 'cause we did a Bossmen reunion at the YMCA in Saginaw and we had, like, 1000 people. It was like, "Wow, people must remember." And I found out that people here in Michigan actually do remember me and were loyal, had listened to and followed my career, and it was very exciting. I still had fans and friends, and my family all live down in Pontiac. So moving back seemed like the logical thing to do.

So I came back here and started putting this together. I got to play with the Saginaw Bay Orchestra –- we did an outdoor thing where they did all my music. It was my first chance to really play with a full orchestra, which I'd always wanted to do. I've done that with them a couple of times now, so I've had a chance to fulfill a few of my dreams. Now it's tough, because I'm here and I've got the studio, and I'm trying to make it run as a business, but basically, I use the studio more as a project studio for groups that I want to get involved with, and groups I want to help. Because I've got the years of experience and I can help younger groups reach a new plateau.

G: Tell me about a couple of the groups on the Wagner Music Group (WMG) label.

G: Tell me about a couple of the groups on the Wagner Music Group (WMG) label.

D: Well, the first record we did here was Matt Besey. He's a 24-year-old blues guitarist a la Stevie Ray, only different. Better than Jonny Lang and...what's the other guy's name?

G: Kenny Wayne?

D: Kenny Wayne! Better than Kenny Wayne [Shepherd]. Besey has something. I went to a party one night and down in the basement Matt Besey was playing. He was 19 at the time. I heard him play and I said "Jesus, man." So I got a guitar and he and I jammed. And I remembered him. When I came back to Michigan, actually moved back here, I put a band together here in town. At least I could get out and play live, play some clubs and just have some fun. I asked Matt to join up with me on second guitar. We did that for about a year and a half. During that time I wanted to make a record with him. I thought he was real good, real talented.

So we ended up doing a record here at the studio, and that was the first release on WMG. I started a little label--not with the idea of becoming Sony Music or anything, but as a vehicle to be able to get records out and help these groups get an identity, get things started. Because for me, it's like, a group comes in and they have a lot of talent, but they don't know where to go, or what to do, so I try to help them at least get a foothold on how to build a career.

G: In all things, experience counts.

D: It does count in this case. What to look for, and what to avoid, and what you have to do, what sacrifices you have to make, and I really try and guide them a little bit. So I built this company as a multi faceted company. We offer advice and management, we have a label for the distribution of the records, we have a studio where we can make the records, and then at some point, if they can get their fan bases building so that they have actual potential for real success, then I can help them make deals, you know, push them on to where I can't really help them anymore, where somebody else can help them out.

So that's my whole idea behind this. It's been working out. We've got some real good groups. My son has a band in Austin, Texas, called Brother Love. He started sending me tapes of their music and I couldn't believe it , it was so good. So I'm prejudiced because he's my son. On the other hand, if you just listen to the album, you know he's got what it takes. He's a singer, the front man. Mr. Charisma. He knows how to really grab an audience. He's amazing.

G: A lot of musicians don't realize that talent is only half the battle. Hard work is the other half. You can't just show up at rehearsal, play for 45 minutes and then go get high.

D: Exactly.

G: You know, work for a couple of hours, then go get high!

D: Well, we try and encourage these bands to avoid drugs, because it gives you a false sense of...I mean, I went through a whole thing in my life, heavy drug abuse for a lot of years. It gives you a false sense of what you're doing, in the end. It isn't that you can't be creative on it or anything, because you can. But there's a point of diminishing returns, where it catches up to you, and when it does you won't even know it. And it's devastating. We don't tell people what to do, but we encourage them to avoid it.

G: If you could, what would you change about the way the music industry works today?

D: I would free up radio to have a more expanded playlist that would include more local music, and I would put record labels back in the hands of real music people who actually care enough to develop and nurture the careers of their artists.

G: So you've put out a new Frost single?

D: We have a single that we just recorded, "This Band Can Rock and Roll Forever." It's really a throwback to the old Frost days. It sounds like a '60's or '70's song. It's really cool. Right now, it's just going to be for sale at the reunion concerts we're playing, but it's starting to get airplay in Saginaw, Kalamazoo, Flint, and Detroit. If it starts to get any kind of response, we'll put it in record stores too. But for now, it's a special thing available at the concerts.

G: I guess you guys are planning to do a bunch of shows?

D: Yeah, we have about 10 dates lined up.

G: How does it feel to be back with your old bandmates?

D: Man, it's great. It really is great. We rehearsed last night and it just sounded so good. It feels right, you know? It's interesting to me because before we had played, or anything, I was worried that "Gee, this music's from a long time ago. Is it going to be viable? Is anybody actually going to like it? Is it going to feel good to play it, or is it going to feel wimpy?" But this music still feels viable. It still feels great.

G: Trends can come and go, you can do all your techno loop sample crap, but in the end, you get a couple of guitars, bass, and drums, turn them up and lock in. There's nothing better.

D: I feel the same way. That's what moves me.

G: That's what's the most exciting thing.

D: Yeah, it is. The rest of it is kind-of fluff. Although it can be used in creative ways, but that fundamental rock and roll band: that's what the Frost is. It's fundamental, basic, right down to the hard-core rock and roll, but with intelligent songs, and good vocals and harmonies. So it's music. It isn't just bang bang bang. It's music, and so I love it. I wasn't sure at first, because when you think about records you made 30 years ago, you're wondering, "that was 30 years ago, how could it possibly...?" But once we started playing, it was like, "Oh yeah, I remember this! That's why this felt so good back in those days." Because it's legitimate.

G: And now all the angst is out of the equation.

D: Now we're just having fun. Working with these guys, they're my friends. They've been my friends for years, and it's just a kick. It really is. And Donny's singing better than he ever did. On some levels, it's even more amazing than it was. Knowing we've had all these years of experience to add to it. We're all still playing well and I think my playing is the best it's ever been. It's just a lot of fun for us...