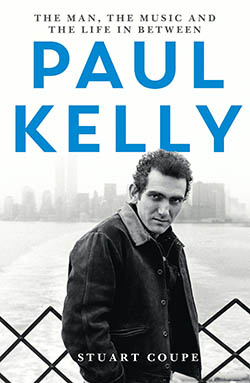

Paul Kelly: The Man, The Music And The Life In Between (Hachette Australia)

Paul Kelly: The Man, The Music And The Life In Between (Hachette Australia)

By Stuart Coupe

“I hear you like music. Do you like Paul Kelly? I’ve just been reading his autobiography, "How to Make Gravy". I love his music. Always have.”

It was an innocuous and inoffensive simple conversation starter one Sunday afternoon, uttered by a friend of my wife’s. To the extent there was question in there, it was almost opaque, and more likely rhetorical. Everyone likes Paul Kelly. How could anyone not like Paul Kelly? As it was, I fumbled around for an answer, and mumbled something about not having had the chance to listen to any of his music for a while.

It wasn’t as if I didn’t like Paul Kelly’s music. I’d first heard and seen him back in the early 1980s on Countdown with his then-band, The Dots. A few years later Kelly appeared again, this time with a new band, the Coloured Girls, and a batch of songs that would become staples of commercial radio playlists: "To Her Door", "Darling It Hurts", "From St Kilda to King’s Cross" and "Before Too Long".

By the time Kelly dissolved his backing band in 1991 – since re-titled the Messengers, to mitigate the risk of offending the American audience he so desperately craved – Kelly was well on his way to becoming a national icon. Then came the deluge of awards, the national acclimations, the profound and pithy observations on Australian cultural consciousness. And somewhere along that journey, for me at least, Kelly became symbolic of an artist defined by a carefully constructed public profile.

Stuart Coupe knows Paul Kelly, and the socio-musical context in which Kelly evolved, better than most. Coupe was Kelly’s manager during that career-defining 1980s period; by stroke of coincidence, Kelly was also Coupe’s first interview subject, way back in 1977 when Kelly was playing in High Rise Bombers alongside fellow Adelaide expatriate, Martin Armiger. But despite that historical and professional association, it took almost five years for Kelly to agree to Coupe’s entreaties to write his biography.

Coupe’s modus operandi is to rely on first-person interviews and, save for the Messengers/Coloured Girls period, the author remains out of the narrative. Coupe is a diligent and informed researcher, sketching out Kelly’s evolution as an artist from his days in Adelaide in the mid 1970's, tracking down old friends and lost travellers from the time. Indeed, the most fascinating parts of the biography concern Kelly’s apprenticeship in Melbourne in the 1970s and early '80s.

Intelligent, talented and perpetually ambitious, Kelly morphs into a protagonist in the now much-mythologised scene of artists, drug takers and sharehouse intellectuals in Carlton and Fitzroy in Melbourne’s inner-north, and south of the Yarra in St Kilda. Coupe’s attention to historical detail is impressive, as is his desire to fill in gaps in the Australian musical historical record.

Judged by the words of some of his contemporaries, the Paul Kelly of 1981 is as selfish and irresponsible as he is well-read and disciplined. Kelly’s fascination with the artistic and narcotic hubris of Baudelaire and Rimbaud eroded his musical, platonic and romantic relationships; Kelly’s publicly expression disdain for his early musical output is arguably rooted in embarrassment at his behaviour around that time, rather than the quality of the music he wrote and released.

The reliance on oral history has unavoidable consequences, most notably the absence of first-person testimony from two of Kelly’s most important collaborators, both of whom had passed away before Coupe commenced his biographical task. Steve Connolly and Spencer Jones were playing together in Cuban Heels when Kelly was at the apex of his inner-city Melbourne pub rock trajectory; one story (not included in the book) has the pair trying to outdo each other in front of Kelly at a Cuban Heels gig, in the vain hope Kelly would choose one of them to join The Dots.

Without Connolly’s distinctive guitar sound and musical direction, Paul Kelly may not have crawled back from the edge of career abyss. While Coupe pays due attention to Connolly’s influence on Kelly’s evolution as an artist, it is intriguing to contemplate what critical observations Connolly would have said about his former bandmate.

Spencer Jones joined Kelly’s band in 1995 – coincidentally, around the same time Connolly passed away, having succumbed indirectly to the perils of alcohol and drug abuse. Jones gave Kelly an injection of rock’n’roll credibility, which lasted until, seven years later, he was a casualty of Kelly’s desire to make a clean break, in more ways than one.

Coupe doesn’t dwell on Kelly’s decision to give up his 25-year heroin usage, presumably because Kelly had already dealt with it in his "How to Make Gravy" memoir. Jones’ assessment of Kelly was prone to equivocation, yet without Kelly’s support in the late 1990s, Jones’ own solo career may have lay fallow.

By the turn of the millennium, Kelly has shed the drug-stained skin of his pub rock roots; everybody loves Paul Kelly, especially the musicians fortunate enough to be dragged into his songwriting and performing orbit. Kelly is supportive and benevolent, hard-working and committed, observant and philosophical.

A friend of mine, who first met an earnest Kelly in Melbourne way back in 1976, told me last year that Kelly was “always pretending to be someone … we all knew he was pretending, but so was everyone else”.

Coupe’s thorough and eminently readable biography is both a valuable addition to the canon of Australian music history, and a timely reminder that what we all now see as Paul Kelly is the culmination of a long journey. As Spencer Jones once remarked, “People say he’s Australia’s Bob Dylan. But he’s not. He’s just very good at the business of being Paul Kelly”.

3/4

3/4