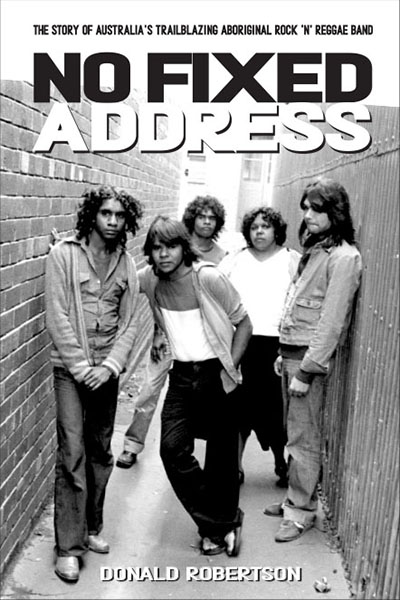

No Fixed Address by Donald Robertson (Hybrid Publishers)

No Fixed Address by Donald Robertson (Hybrid Publishers)

“No Fixed Address” is a magnificent achievement. It's also readable, interesting, engaging and fucking disgusting.

We'll get to the latter comment in a bit.

As you know, one of the few benefits of lockdown was that some great work has emerged - but we're damn lucky it's Donald Robertson who decided to write about No Fixed Address. He was there at the time, was an aware chap, and wrote extensively about the scene he was so much a part of in Roadrunner magazine. Also, Robertson's approach resembles that of a historian approaching The Rolling Stones.

Why? Well, while you may not have seen them, or even heard of No Fixed Address, the band's importance in Australian Aboriginal history is bloody enormous. Robertson gets this so well that, in the opening chapter, we discover that NFA would not have existed but for the determination of a number of significant people to encourage, enthuse and integrate Aboriginal people into the Adelaide arts culture, long before the band had learned to play.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, this was fairly unheard of; so it is, in a way, no surprise that names like Leila Rankine, Catherine Ellis, Ted Strehlow and Veronica Brodie all turn up as incidental characters.

Don't recognise the names? Go to the “Australian Dictionary of Biography” (aka the ADB online); you don't get an entry in there for sitting on yer bum watching “Drone and Away”, “Australia's Got Alkies”, “These Kitchen Fools” or “Married at First Fart”. (ED: You left out “The Farmer Wants a Root”.)

Without wishing to expand on this, a huge number of intellectual, ethnographical and forward-thinking visionaries inhabit the fringes of the No Fixed Address story, all important to the way things happened. Thirty years after their death, some are commemorated in the ADB. Others have biographical records on the websites in the history section of a number of government departments.

The further in I delve, the more hooked I am. Here's Adelaide, a place I grew up in, with all these familiar names and places and ... there's an entire strata of society that I must've known existed, but didn't know anything about. For example, Robertson tells us a little about the history of Adelaide's Centre for Aboriginal School and Music (CASM), a hugely significant concept which was incredibly helpful to many troubled young people. Which makes me wonder, in a modern Australia beset by “youth crime” why on earth more similar centres aren't trialled around the country.

Robertson quotes artist Leigh Hobba; "You travel with them on a bus somewhere and you can just feel the tension that those people had to live with day by day. It was quite powerful and palpable. The difficulties of their life. So, they would come to CASM and they would sit down, and they would find some kind of safety there ... [music] was the element, you know, that allowed that sort of safety and structure in their life, apart from giving them a bit of money. There was a community trust in there. It was a safety net for a lot of people."

Robertson's thumbnail sketch of the Aboriginal experience over the years is clearly the tip of a very large historical iceberg, with many forgotten lessons.

There's a lot I don't know about Aboriginal history, and I won't excuse my ignorance because I can't. Reading Robertson's book is like unpeeling an enormous walnut, the more you discover, the more you realise how very much more there is to discover.

For example, I didn't know the difference between “assimilation” and “integration”. Apparently only three Aboriginal families were allowed to live in each town. Which is ... you know, stupid. Surely! On page 51, I learn that, in 1962 "(South Australian Premier) Don Dunstan successfully argued forcefully against the policy of assimilation. Instead, he said, a policy of integration should be adopted. His arguments were accepted and South Australia, alone among the states, moved its policy settings away from assimilation."

The first of many reforms, which “may seem small steps today, but in the mid-1960s they were close to revolutionary and attracted strong criticism”.

Integration only appeared, against much opposition and inertia, for god alone knows what reason, in (I think) 1972. Fifty years ago. Understanding all this stuff is as crucial to the No Fixed Address story as drug laws and the attitude of the police were toward hippies, the Beatles and the Stones in (say) 1967: "The relationship between the police force and Aboriginal people at the start of the 1970s was steeped in mutual hostility ... despite the repeal of much of the discriminatory legislation ... on the ground victimisation by the police and the criminal justice system continued virtually unabated.

“Aboriginal people were disproportionately arrested for trivial crimes, such as drunkenness, vagrancy, indecent language and disorderly conduct. Once arrested, they were much more likely to be denied bail and to be convicted. Then, once convicted of minor crimes, they were much more likely to receive a high fine, to be sent to jail and to be given a longer sentence."

This is how an underclass is created when we don't need an underclass.

I remember the main drag of Hindley Street, Adelaide on a Friday and Saturday night back in the 1970s and 1980s. If the cops wanted to make a killing with fines for "drunkenness, vagrancy, indecent language and disorderly conduct" it would have taken them about an hour to completely fill the local nick.

With “white” folks, I mean. But, it never happened. It was rare, except in the case of 'punks', to be arrested for stuff like that. Boy, the police were really exercised about punks, killing several gigs (not mentioned in this book as NFA weren't playing) with an indiscriminate and entirely unnecessary show of force similar to that shown at NFA's Port Adelaide Town Hall gig.

The cops learned from that near-riot at the Port Adelaide Town Hall gig; in future, they would infiltrate the venue; the band on stage would ask if they could help the cops, who might arrest some drongo who was barely conscious on the floor ... and then, possibly at a given signal, all hell would break loose as the cops would arrest everyone they could, for whatever they could.

Folks would scamper out the venue any old how, through windows as well as doors, only to discover a large number of coppers and paddy-wagons waiting outside. I recall reading Harry Butler's DNA zine which recorded one such event (which I'm glad I missed) where one character had been charged - actually charged - with “dangerous dancing”. The charge was, of course, laughed out of court the next morning.

It would be nice to think we've come a long way since then, wouldn't it?

Of course, such jolly policies as integration and assimilation took the view that the Aboriginal people would be ever so pleased to join in the fun and games of 'civilised' society. Never mind the unjustifiable mistakes and entirely ruinous damage caused by policies of 'let the paedo prey' and so on, we'll let you join our wonderful society.

Quite a lot of folks don't emerge well from this book. The police, in every state, it seems, had problems with them. The SA Police Commissioner at the time was Laurence Desmond Draper QPM (1923-2016). Some of the incidents ... well, let's just say either the orders came from the top ... or the responsible minister ... or they happened without their knowledge. Either way ... sigh.

And the powers that be wonder why they're mistrusted. Bungling at the very least, poisonous and cruel intent at the worst. I had tears in my eyes as I read the short bio on Bart Willoughby. We're such a lucky country...

Whether I like it or not, the one thing which stands out in “No Fixed Address” like the proverbial dog's balls on a birthday cake - how kneejerk ingrained, and how utterly stupid, actual racism is. Doesn't matter which country, or which colour or culture we're talking about.

Look, we can all understand feeling a certain wariness should an instantly recognisable member of any given particular group head down the street. But you don't need to react like every one of this group is some sort of monster. I mean, if someone who strongly resembled Scott Morrison were to amble down the street, I admit I'd have to restrain myself from booting the bugger in the bollocks as hard as I could (I'd call 000 immediately afterwards, of course, 'cos I'd need to be treated for shock and stress).

But apparently, “justifiable outrage” is not a mitigating circumstance in Australian law, so I'd expect to be fined at least, ooohhh ... say, $30? If it were Scott Morrison, of course; but with my luck I'd be more likely to wallop away and find that the poor fucker was a harmless plumber called Graham and this is the fourth time he's been booted that day. See, prejudice. It's stupid and you'll almost certainly get your prejudgement wrong.

Take “No Fixed Address”, the band's name. They took it from a play of the same name by Chester Schultz; many years after being thrilled by the band No Fixed Address, I first encountered the government reality of what the acronym NFA meant to the DSS, CES, ATO and a host of other agencies, what it meant in reality was, a disordered homeless person who was unlikely to turn up for an appointment, provide reasonable identification, and would always be causing more bloody paperwork for the hard-working staff.

In a review of the recent live NFA CD, I wrote; "No Fixed Address (or NFA, as the Social Security acronym had it) was what every itinerant/traveller/boho put down as their address when they turned up in a strange town and went to lodge their form. Meant they weren't entitled to rent assistance".

At the time, there was a semi-permanent series of creative-packed caravans trekking the length and breadth of the country. No Fixed Address certainly were a part of that.

So. Er, what was the music like, then, gGandad?

Well, in the review, I say, "They were young, gifted and Aboriginal, talent rising off them like heat waves, NFA had an intimate, natural grasp of reggae and bent it to their will (astonishing given their age), [with] cracker out-of-time original songs [which] they move and groove like a long, slow fuck in the twilight."

But wait, there's more: "Steve, Fred, Paul and me would go down the the Governor Hindmarsh, long before its marvellous refurbishment a couple of decades back, and we'd see all manner of bands: The Lounge, Systems Go, Drum Poetry, No Fixed Address. We'd heard NFA on 5MMM FM radio (they'd put out a demo tape) and we were duly impressed, not least by their extraordinarily natural ability to weld reggae into something more modern and relevant. In an era where there were a lot of bad and iffy bands out there... for a while there (perhaps late 79 - the memory is a tad hazy - but certainly) during 1980 [and 1981], it seemed like we went every time NFA played.

They were so very good, they had a soft/strong groovy vibe to them, with John Miller's lyrical and wraparound throbbing bass critical to their sound, a smart drummer who knew how to spread his beat around the kit and use cymbals properly - who was also that rare beast a drummer whose vocals actually worked - no, hang on, Bart Willoughby had one of those marvellous, yearning cracking voices you hear once in a decade if not less frequently. Oh, and two guitarists, Leslie Lovegrove Freeman and Ricky Wilson, who filled things in beautifully, and Veronica Rankine who played (from memory, occasional, sax). The entire band was the next best thing to a work of art."

Graeme Isaac recalls; "Their sound was sometimes rough as bags ... but there was an energy about them, and also, you can feel they were writing ... this was really new, what they were doing. They were writing songs about their own lives but in the contemporary idiom. There'd been plenty of Aboriginal bands ... but they were all country bands."

There are so many stories here; Robertson's hinted at a few on his Facebook page - how No Fixed Address got dudded at the SA-FM Summer Search, how they got raided by the cops backstage at the Festival Theatre after playing for Prince Charles. Jimmy Page was a fan.

I could write about this book for another ten pages, easily, but sod you, frankly. You shouldn't need me to. “No Fixed Address” is one moving, anecdote-packed, roller-coaster of a book. Your jaw will be flopping open like a pooch suddenly receiving a suppository. Which I guess might be part of the point. Get it, read it, weep, see the band live and get into their music.

The book is available from a lot of record shops, but if in doubt, pester Donald Robertson here or the publisher here.

Stream NFA here, buy tickets to see the band in Sydney on May 18 and catch the CASM exhibition in Adelaide.

![]()