Griffin grew up in the southern state of Kentucky. It was, Griffin says, a “happy childhood, unlike so many people in the arts”. Griffin’s interest in music was sown when, while recuperating from an extended period of illness, he “became addicted to the radio”, well before the British Invasion hit American shores.

“I grew up in that great era of AM radio in the 1960s, when you just had to turn on the radio and there was something on, pretty well to the end of the decade,” Griffin says. “And I confess that, to this day, I still have an affection for AM radio.”

By the time he was 22, Griffin had re-located to Los Angeles. “When I got to LA, the punk thing was breaking. You could do anything. There were all sorts of crazy things that didn’t make any sense,” Griffin says. “I saw a band at a band opening up for The Go-Gos in San Francisco, and this band, astonishingly enough, was the only band I’d ever seen where every single person in the band had a physical handicap. That was the punk I liked. You’d had the scene where it was all white men with guitars, and now there were women, people of colour and this band I saw that were physically challenged. I loved that.”

Griffin had been excited to see The Ramones for the first time in 1976; he didn’t realise the bands in The Ramones’ wake would be so often cheap imitations of The Ramones, Sex Pistols and The Clash. Griffin’s response was to join a garage revival band, The Unclaimed.

“We wanted to do something more liberating and fun,” Griffin says. “I didn’t realise anyone else in the world was doing that sort of thing til I heard about bands like The Fleshtones, The Chesterfield Kings and The Droogs. So The Unclaimed was part of a re-charging of the batteries for me, and a part of my history I’m really proud of.”

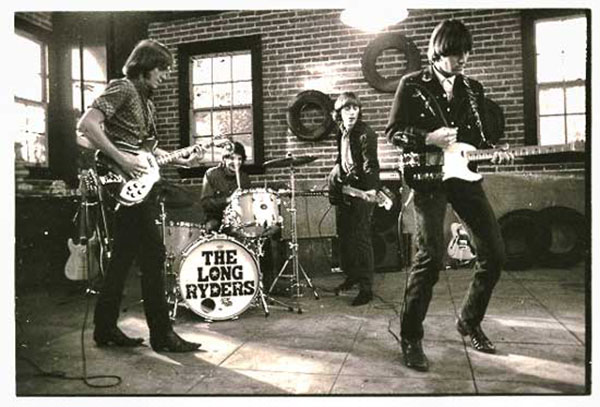

Tom Gold photo.

Tom Gold photo.

At the turn of the decade Griffin and Unclaimed bass player Barry Shank decided they wanted to move on. Griffin and Shank found a drummer, Greg Sowders; when guitarist Stephen McCarthy came on board, Griffin and Shank decided to exchange fuzzy garage nuggets for country style.

“Stephen had a big dollop of country and western in him,” Griffin says. “Stephen saw The Ramones and The Damned, but didn’t really like. He’s not a Clash guy, he likes Merle Haggard and, long before it was fashionable, he was that alt.country person. So when we got Stephen in the band, it was inevitable because he was such a strong musician, he was pulling us away from that 60s sound that Barry and I were fixated on.”

Shank eventually went back to university – these days Shank is Professor of Comparative Studies at Ohio State University – to be replaced by Tom Stephens. Stephens appreciated both the ‘60s revival aspect and country and western. From here, The Long Ryders “fell into their market”, Griffin says.

It was, Griffin muses, incongruous that anyone in the punk scene would be remotely interested in country and western music. “No-one, and I mean no-one, who saw The Clash and The Sex Pistols like country and western – apart from Rank and File, who had a clean Buddy Holly style,” Griffin says. “Stephen and I were doing The Everly Brothers’ "Brand New Heartache", some other stuff, and we were amazed that people liked it. And I was even further surprised when guys like John Doe, of X, and other luminaries of the LA punk scene, like Keith Morris, who took aside and told me how much he liked The Long Ryders, I was blown away.”

Griffin concedes that The Long Ryders weren’t a “C&W band”, but their styling was unashamedly country. “Many young people of the day, back in the early 1980s, told me they’d never seen a country and western band play live,” Griffin says. “And many people also told me they’d never seen a young band do a country and western song. They might’ve been dragged to a country and western band by their father, which they hated when they got there. So that confluence of country and western music with punk attitude really got you The Long Ryders”.

A friend of Griffin’s told him recently that Griffin’s “great cultural contribution might be making Gram Parsons a household name and making Gene Clark more of a name”. Griffin, who wrote a biography of Parsons in the mid 1980s, says Parsons was largely unknown when The Long Ryders started out.

“The Long Ryders came over to Europe and we’d do all these interviews, and when people asked us who we listened to, we’d say Gram Parsons, and no-one knew who we were talking about. They thought we were talking about Gram Parker! I don’t remember any hip music writer knowing who Gram Parsons was!”

So, too, had former Byrd Gene Clark stumbled into alcoholic obscurity. Long Ryders guitarist Stephen McCarthy had played on a couple of Clark’s records, and bass player Tom Stephens had been Clark’s band. When The Long Ryders came to record their first full-length album, “Native Sons”, the band invited Clark to sing back-up vocals.

“Gene was a lovely guy, but he was crippled by alcohol,” Griffin says. “Sober, Gene Clark was one of the nicest guys I’ve ever met, but drunk he was wild, and I mean wild. It wasn’t like he wanted to start a fight with you, but he wanted to do crazy-assed stuff. He had this crazy look in his eyes. And it’s a shame, because all Gene had to do to be famous was to stay sober and stay alive, because the wheel was turning towards Gene Clark.”

“Native Sons” had nudged The Long Ryders toward the top of the college charts in the United States and attracted significant attention overseas, especially in Europe. The band’s next album, State of Our Union, led by the lead single, "Looking for Lewis and Clark", threatened to push The Long Ryders over the threshold from college radio staple to commercially successful proposition. But that hoary old chestnut, record company deceit, put a stop to the band’s next quantum leap.

“The single was about number 57 on the charts, which meant it was probably going to be in the top 40 the next week, and Island Records had an acrimonious meeting. There was a whole echelon of Island Records who were saying guitar music is over,” Griffin says.

“So 'Lewis and Clark' is climbing the charts, and we’re having this very acrimonious meeting, lots of shouting and screaming. And the guy defending us, a guy called Nick Stewart, got them to agree to a budget to continue to manufacture the single, which was selling out, we’d sold about 50,000 copies in America and about 30,000 copies in Europe, so they were running out. He got that pushed through, in a really ugly debate.”

But a week later, when the supply of pressed singles ran out, The Long Ryders discovered their bete noir at the record label had lied. There were no more copies being pressed and, to make matters worse, Christmas pressing schedules meant that none would be pressed before January. The single promptly fell out of the US charts. Around the same time, The Long Ryders were offered an Australian tour, only to turn it down in favour of a far more lucrative tour of Spain, including a headline spot at an outdoor festival in Barcelona in front of 100,000 people.

By 1987 The Long Ryders were wobbling. Tom Stephens wanted to recalibrate the balance between his life on the road and his young family. Drummer Greg Sowders was battling alcoholism. Griffin wanted to keep The Long Ryders on the road with a couple of replacement members, but in the end, after turning down a second Australian tour, agreed to draw a line under the band. ”Greg Sowders had a marvellous statement. He said The Long Ryders broke up, Beatles style – which means money problems, girlfriend problems and ‘Hey fellas, what about recording some of my songs?’ problems,” Griffin laughs.

The Long Ryders went their separate ways, rarely communicating over the next 17 years. By the early 2000s offers for a Long Ryders reunion started coming in. Eventually, helped in part by the increasingly lucrative financial offer, Griffin overcame his initial indifference to reforming. Griffin contacted the Sowders, McCarthy and Stephens and suggested they do a European tour in 2004. “When we got together, the dynamic was a little weird, but we got over that. We’ve all grown up a lot, so that helped.”

Sporadic reunion shows followed over the next decade. But in an interview in 2016 to promote the release of the Long Ryders, boxset, “Final Wild Songs”, Griffin asserted The Long Ryders would not record a new album. Three years later, The Long Ryders released its first new album in 32 years, "Psychedelic Country Soul".

“Stephen was the first to say he wouldn’t continue if we weren’t going to any new songs, and I was the last because I didn’t think anyone cared,” Griffin says.

The catalyst for The Long Ryders’ new album came courtesy of sometime Parliament/Funkadelic bass player Larry Chapman, who The Long Ryders had befriend some years earlier. “When Larry came out to LA in the 1980s, The Long Ryders were a big deal and we got him some jobs, because he was hurting at the time,” Griffin says. “He kept saying ‘I’m never going to forget you Sid Griffin, I’m going to pay you back.”

In August 2016 Chapman rang Griffin from LA, where Chapman was now working with Dr Dre, and offered The Long Ryders a week’s free studio time in Dr Dre’s “state of the art” studio in LA (the same studio, Griffin remarks, once owned by Val Garay where Kim Carnes recorded "Betty Davis Eyes").

Greg Sowders, over a decade sober and now a senior publishing executive at Warner-Chappell, was given the role of songwriting arbiter. “Everyone gave four songs at a time to Greg, and eventually we had about 14 songs, and we recorded them, and Greg decided which ones would stay,” Griffin says. “It ended up going really well, and I’m proud of that record. I hope we get to make another one before I die.”

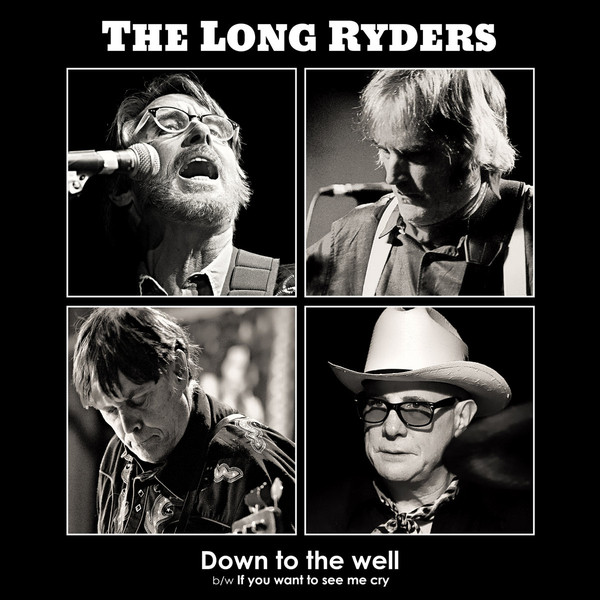

The Long Ryders’ latest release, “Down to the Well”, returns to a theme Griffin explored on The Long Ryders’ almost hit single, "Looking for Lewis and Clark".

“I wrote that song, asking where the American daredevils and heroes were – we were stuck with Ronald Reagan and that ilk,” Griffin says. Prophetically for today’s America, the album title itself pointed out the fault lines in American society exposed by trickle-down economic policies.

‘Down to the Well’, Griffin says, asks “how did we get into this mess?” “The people who we call Trumpites now, they’ve always been there. We had America First rallies in the 1930s. Or look at the Snopes trial in the 1920s,” Griffin says.

These days Griffin lives with his family in London, just north of King’s Cross. At the time of our interview, London has just gone into lockdown in an effort to stem the recent surge of coronavirus infections. For the foreseeable future, getting The Long Ryders back on the road seems an abstract prospect.

“We’re keen to come to Australia,” Griffin says. “There’s a guy, David Roy Williams, who wants to bring us out. So whenever we can, we’ll be there.”

"Down to the Well" is out on Prima Records. Visit The Long Ryders on the Web.

Making orange juice from oranges...Sid Griffin and The Long Ryders. Tom Gold photo.

Making orange juice from oranges...Sid Griffin and The Long Ryders. Tom Gold photo.