I’ve read that you were initially reluctant to put your first solo record out. Did you have any such reluctance with “Detroit Blues”?

No. I might have a reluctance to do a third one because maybe it might not warrant a third record in the same vein. But for the second record, no. I’d learnt a bunch of songs and wanted to record them, so I did.

What is it about the songs, both lyrically and musically, that you’ve covered on this record, that attracted you to them? What is it about a historical tune that piques your interest?

Something that’s simple enough that I can play! I like words and something about the words I’ve chosen means something to me that I can’t explain. I think things that are a little bit droney. Simple, raw and droney. Things that maybe have an ambiguous theme, or a universal theme or a universally ambiguous theme!

What about a song like “House of the Rising Sun”, which has been covered by a lot of bands over the years. What do you look about giving to that song which hasn’t been present in other recordings?

It’s a song that I really love. I love hearing different versions of it. And I like to shamelessly cover songs that have been done a million times. I think maybe if I saw someone else doing it I wouldn’t be that interested, I don’t know. It’s kind of challenging to do a good version, an interesting version of a song that’s been done so many times.

What about the instruments you played on this record? You learnt a bunch of old instruments for your first album. What did you discover or learn for this record?

The Gories.

The Gories.

I didn’t discover anything. All this stuff has been going on for years and years. They’re just old things that I’ve picked up because I like them. I play a one string bass that’s made out of a metal five gallon can, a wash line and a stick. Those things have been around forever.

I like home made stuff, I like things that have an ambiguous pitch. When you’re playing a one string bass, the pitch is controlled by how tight you hold the string. There’s a pole attached to the string and you tighten the pole back and that tightens the string. So it’s got a very nebulous pitch. The same with one string instruments, there’s no frets on it, you just have to find the note. It’s like pulling notes out of the ether, or something. I’d like to get a fretless banjo, that’s the next thing.

Detroit has a rich industrial and mechanical history. Do you have a natural interest in DIY instruments?

I suppose so. I’ve always liked making things. My grandfather was a woodworker and carved birds, decoys. So I’ve been around making stuff. But it doesn’t really have much to do with Detroit except a lot of people around here know how to do and make things.

The thing about Detroit is that so many folks from the south, southern United States, moved here. It’s almost like a bit of the south in the north. And they brought so much of that good music from down there, the blues, bluegrass, that kind of stuff. So there was a big culture for that kind of music here. It’s mostly died but it’s still around if you look.

Nick Tosches wrote a great book some years ago about the “twisted roots of rock’n’roll”. One of the perverse aspects of that historical journey was unearthing the minstrel, country-blues artists like Emmett Miller who had a subliminal influence on how rock’n’roll came to be. To what extent have your own musical expeditions led you to parts of American cultural history you weren’t aware of?

Nothing that I wasn’t aware of, maybe deepened my understanding.

You mentioned the word “minstrel”. That whole thing is really interesting because the minstrel show is a deep part of American culture and something that a lot of people don’t talk about. There are some really good books about it. There’s a very academic book, called ‘Love and Theft’ and I think Dylan got the name of his album from this book. There’s a lot of songs from the 1880s and 1890s that fellas recorded in the 1920s and in the 1920s those songs were already old. And a lot of that stuff came out of minstrel shows in the 1800s.

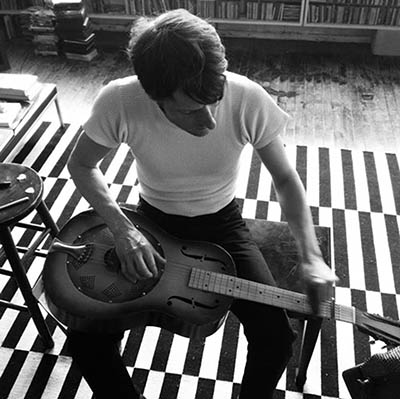

You recorded your previous album on the second floor of a building in Detroit. Where did you end up recording this album?

In a friend’s loft, which is an old industrial building – there’s a lot of old industrial buildings around! He had this real big loft with nice wooden floor and high ceilings, we set up some nice mikes and I just played and sang, right there in his loft. And I over-dubbed percussion and the bass, the jug and the one-string bass. But the basic tracks were me playing and singing live.

So how long did you take with the recording process? Was it important not to over-engineer it, so to speak?

It may have been three or four sessions of maybe three hours each. So it only took about 8 or 10 hours, I guess.

In addition to the improved or refined fidelity, how do you think the album has evolved from your previous solo record?

The fidelity is better, for sure. And I guess I’ve got a better grasp on what I want to do, what I’m trying to do. But the main difference is the fidelity – it’s a better sounding recording.

When you listen to the original recordings of the songs that you’ve covered, to what extent do you think the lower fidelity of those recordings is intrinsic to how evocative they are?

I don’t think it’s intrinsic. I kind of wish I could listen to the original recordings from the 1920s in really hi-fidelity. And some of those records, if they’re in really good condition, they’d sound phenomenal. Unfortunately some folks like Blind Lemon Jefferson and Charlie Patton were on Paramount and those records were just poorly made. The materials they used to make the disc were just poor materials, so they don’t sound very good.

But there are 78s from the 1920s that sound really great, really live and full. I just wanted the sound of someone playing live in the room. And it’s quite good sounding room, that loft with the nice wooden floors and high ceilings and to me, that’s a good place for recording anything.

On one interpretation, rock’n’roll history is just about re-invention and re-interpretation – there’s nothing fundamentally new to be created, only new signposts to find. Does that resonate with you?

Past music resonates with me, for sure and it always has. But, yeah, that’s not much new to do, it’s just a new twist on an old thing.

When you look back on the music you were playing with The Gories and even before that, can you see the subliminal influence of the music you’ve discovered more recently?

Yeah, but I think I just attitude more – attitude more has an influence on my music. Because you can find the same attitude in older stuff. A lot of the 1920s and 1930s blues music was the gangster music of its time and some of it has a gangster attitude to it.

Are you comfortable with this record being labelled a “folk” record?

Yeah, for sure. I don’t think it’s really a blues record, even though I called it “Detroit Blues”. I like to mix it up a little bit. It’s kind of a folk-blues-gospel thing, maybe a little bit of hillbilly in there too [laughs].

Without wanting to delve too much into politics, to the outside world the United States seems like a country tearing itself apart from within. Where do you think American folk music fits within that ongoing philosophical drama? What does folk music tell you about where America is now and where it might go in the future?

Wow, man. I think about the part of it where there was a common pool of songs back in the 1800s, maybe even before that, that working class people knew and sang and it didn’t matter what colour you were, they were all common to the American tradition. Folks put their own flavour to them but a lot of that stuff was from a common pool and everyone contributed something and sang together. I don’t know man, I’d just like people to realise there are more similarities than differences.

Do you think there is another folk-blues-gospel record in you in the future?

Maybe. I’m not sure right now! [laughs]

"Detroit Blues" is out now omn Third Man Records. But it here.

Danny Kroha is best known as one-third of seminal Detroit garage punk band, The Gories, which he formed with fellow Detroit residents Mick Collins and Peggy O’Neill in the mid- 1980s. When The Gories’ rudimentary internal infrastructure eroded in the early ‘90s, Kroha moved on to a series of projects, most notably the more theatrically-bent Demolition Doll Rods.

Danny Kroha is best known as one-third of seminal Detroit garage punk band, The Gories, which he formed with fellow Detroit residents Mick Collins and Peggy O’Neill in the mid- 1980s. When The Gories’ rudimentary internal infrastructure eroded in the early ‘90s, Kroha moved on to a series of projects, most notably the more theatrically-bent Demolition Doll Rods.