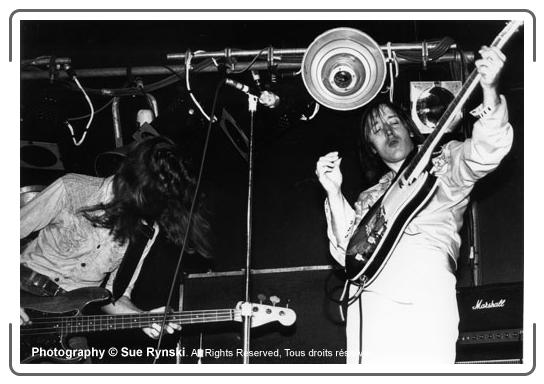

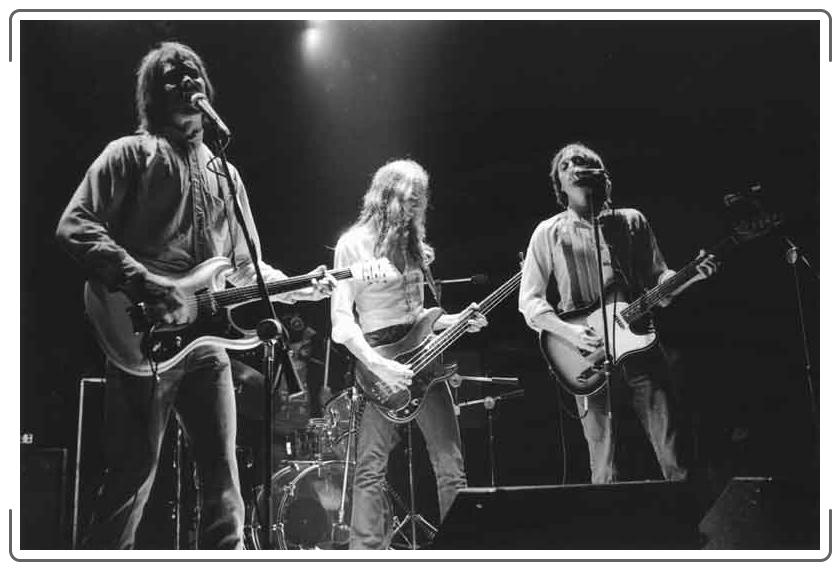

Bloodied but unbowed by the implosion of his former band, "revolutionary" radicals and rabble-rousers the MC5, Fred "Sonic" Smith was fast evolving past his roots in Berry/Stones drive into a guitarist/songwriter/singer of unmatched emotional directness and power. Joining him in the Rendezvous frontline was the former Rationals' blue-eyed soul-brother supreme Scott Morgan, arguably the finest American rock singer and himself no slouch as a songwriter and guitarist. The Rendezvous was more than just a band that rocked hard, although they did THAT with a vengeance.

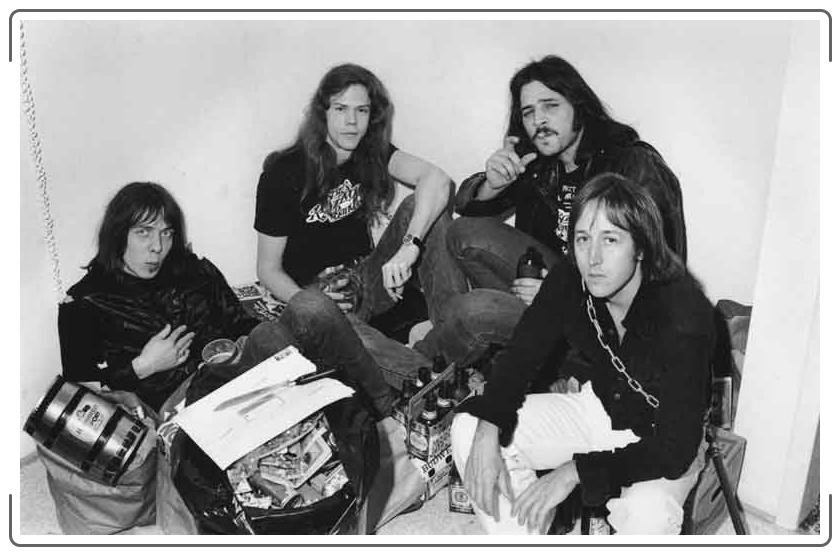

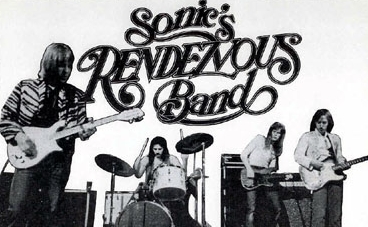

Sonic's Rendezvous Band in 1977. Fred Sonic Smith, Gary Rasmussen, Scott Asheton and Scott Morgan. Robert Matheu photo

The confluence of Fred's spirituality and Scott's soulfulness made them much, much more.. Add the rhythm team of former Up/Uprising bassman Gary Rasmussen and powerhouse skinsman Scott "Rock Action" Asheton (who'd stoked the engine room for the Stooges in all their incarnations, from "Psychedelic" to "Iggy & the..."), and you had a formidable combination of talents. They never performed more than a few hours away from their home base in Ann Arbor. Throughout their existence, they only released a single song on vinyl...the searing "City Slang."

Yet, for 30 years since their demise, their legend has steadily grown and spread through word of mouth from the few who were there, as well as a handful of audience tapes which continue to pass from hand to hand, fan to fan. Today, as a result, bands from Stockholm to Seattle to Sydney cite them as an influence. Recent releases of studio and live Rendezvous material make it easy for anyone to hear what the band could deliver in performance. But Gary Rasmussen has indicated that in rehearsals, the band would warm up with jams a lot more free-form than anything they ever played publicly (although audience recordings of "American Boy" provide a tantalizing taste of what those jams MIGHT have sounded like). In more ways than one, this band was THE ONE THAT GOT AWAY.

It seems criminal that they never found a wider audience in their day -- and begs the question WHY NOT? Part of it has to do with the fact that they weren't charismatic PERFORMERS in the way the Five or Stooges were. Scott Morgan freely admits today that "we just stood there looking at our shoes." But why was their recorded legacy so scant? Why would a band with 30 or 40 good original songs only record TWO of them in the studio? Granted, the Rendezvous drama played out years before "DIY" was the generally-accepted way to go for up-and-coming rock'n'roll bands...these guys came from an era where a label signed you up and handled the marketing and distribution of your product. But why was there no effort to at least demo the material for label consideration?

Undoubtedly, this was a band with some built-in complications, the most obvious being the creative tension between Fred Smith and Scott Morgan. The band's zenith probably came at the point when the songwriters' input was about equal, around 1978. But was the dynamic between the two a limiting factor for the band? One wonders, for instance, why a vocalist as limited as Fred would have sung songs he didn't write, while a singer of Scott's caliber stood mute in the background, strumming rhythm chords -- an arrangement as self-defeating as having Scott playing all the lead guitar would have been. (For his part, Morgan speaks as highly of Fred's vocal ability as he does of his partner's instrumental and compositional skills.) Or why the band (minus Morgan) left Detroit to tour as Iggy Pop's backing band on the eve of the "City Slang" single's release.

Which highlights another problematic area: the business direction of the band. Enthusiasm Scott Morgan has in spades, but a businessman he clearly is not. Likewise, personal charisma and influence Fred Smith might have possessed, but he was never a BANDLEADER in the sense of stating a direction and insuring that things got done.

Today, we can only wonder what his intentions were, and why did he finally pull the plug and withdraw from public performance (following his 1980 marriage to punk poetess Patti Smith)? Sonic can no longer speak for himself, having left the planet in 1994 (following his MC5 brother Rob Tyner, who departed in 1991).

PROLOGUE

Frederick Dewey Smith was born in West Virginia on September 13, 1949. As a child, he moved with his parents to Lincoln Park, Michigan, a downriver suburb of Detroit, part of the exodus of white and black workers from the rural south to the greater opportunities of the industrial Midwest.

The Smiths had a guitar around the house, and a neighborhood kid and aspiring guitarist named Wayne Kambes started coming around and showing Fred chords to songs. Fred learned fast and was soon playing in a band called the Vibratones. (Wayne played in another, rival band called the Bounty Hunters.) Fred had bought a Fender Duo-Sonic guitar, which he didn't like and subsequently returned to the store, but he liked the name and kept it for himself: Fred "Sonic" Smith.

Southern Michigan in the early sixties was primed for a rock 'n' roll explosion. Workers in Detroit's auto industry were making good paydays, which translated into plenty of disposable cash for a generation of factory workers' kids. Teen clubs, like Punch Andrews and Dave Leone's chain of Hideouts, were thriving. The influence of a vital R&B scene (of which Motown was only the most conspicuously successful element) put the emphasis on strong rhythm sections and PERFORMANCE. Dozens of records by area bands were released on a proliferation of small, independent labels, and actually made the local charts. Some were even picked up for distribution by national labels - as when New York producer Bob Crewe reinvented a whiteboy R&B band from the Motor City called Billy Lee & the Rivieras as Mitch Ryder & the Detroit Wheels, who went on to score big national hits like "Devil With a Blue Dress On" and "Sock It To Me, Baby."

The college town of Ann Arbor, 40 miles from Detroit, added an element of hip bohemianism and political consciousness that would be another important influence on the nascent Detroit rock community. In 1964, Fred and Wayne (now calling himself Wayne Kramer) started a new band, the MC5 (for Motor City Five) with a local beatnik/sci-fi/jazz and blues fan who'd been recently converted to rock by hearing the Rolling Stones: Rob Tyner (ne Derminer). Pat Burrows on bass and Bob Gaspar on drums completed the lineup. They played the usual gigs for a teenage band of the time...parties, weddings, school dances, teen clubs, a few scattered bar gigs.

The band took their cues from James Brown, whose performance they'd witnessed in the 1965 film The T.A.M.I. Show, and the harder R&B-based British Invasion bands like the Stones, the Kinks, Them, the Yardbirds, and the Who. Spurred by these inspirations, the young band began experimenting with higher volume and feedback. Their first original composition was a room-clearing free-form assault called "Black To Comm."

Eventually the original rhythm section, whose tastes and ambitions were more conventional than Smith, Kramer, and Tyner's, departed and were replaced by Wayne's neighbor Dennis "Machine Gun" Thompson (ne Tomich) on drums and a converted folkie-strumming Bob Dylan fan and ex-art student named Michael Davis on bass. Although Fred was still "just the rhythm guitarist," both rhythm team members recall he was already showing sparks of creativity.

DENNIS THOMPSON: Fred was the creative musical person in the band, the most musically driven. Like Brian Jones in the Rolling Stones, he would come up with the coolest guitar parts, and Wayne Kramer was more or less the icing on the cake.

MICHAEL DAVIS: When I first got in the MC5, Fred and I shared an apartment in downtown Detroit...We'd sit up all night and play the acoustics and Fred had this little tiny amplifier that he'd plug in; at that time he had a Gretsch Tennessean...I guess that's where I first really started to check out how original of a musician Fred was. These things he'd come up with...he'd play them over and over and over again and you'd never get tired of 'em. It was just like, "Let's hear it again," you know, and he's playin' whatever that part he was working on and he had this kind of mesmerizing, I would call it original style. He didn't ever sound like anybody else. It was always coming straight out of him.

Fred's individuality extended to his choice of instruments. For most of the Five's career, his two favorites were a Mosrite - signature guitar of the surf instrumental band the Ventures and definitely unhip in the era of Les Paul and Stratocaster-slinging British guitar heroes - and an Epiphone Crestwood Deluxe, one of only 200 manufactured. In the later days of the Five, he'd adopt a Rickenbacker 450, another extremely unfashionable model, but one that suited his particular needs.

One of the top bands on the Detroit scene was the Rationals, four Ann Arbor teenagers who'd been together since junior high school. Under the tutelage of Discount Records manager and A-Square Records impresario Hugh "Jeep" Holland, they'd evolved from Brit Invasion wannabes into blue-eyed soul brothers in the manner of their favorite band, Young Rascals. Their third single, a cover of Otis Redding's "Respect" (recorded a full year before Aretha Franklin's), was picked up by Cameo-Parkway and made it to the lower regions of the Billboard Hot 100. At the end of 1966, radio station WKNR named the Rationals "the most popular group in Detroit."

SCOTT MORGAN: When I first met Fred, he didn't say ANYTHING. He was real quiet, and I talked to Wayne. Wayne was the exact opposite. He said, "Oh, that's Fred. He's trying to grow his hair longer than Brian Jones!" That was my first memory of Fred.

In an effort to win over the budding hippie community, the Five pursued a relationship with John Sinclair, a poet, music critic, and leader of a community of artists and writers called the Artists Workshop that had coalesced around the Wayne State University campus. Finally, Sinclair agreed to serve as the band's manager. The Artists Workshop evolved into the Trans-Love Energies commune (and later, as they became more politicized, the White Panther Party). The Five moved in with the commune and they forged a symbiotic relationship: members of the commune designed stage costumes and concert posters for the band, while the receipts (such as they were) from the band's performances supported the commune.

Around the same time, a Dearborn high school teacher named Russ Gibb returned from a visit to the West Coast and opened Detroit's first "psychedelic" ballroom: the Grande. The Five became his house band, continuing to develop their stagecraft and gaining notoriety for blowing a number of touring acts off the stage (a common practice among Detroit bands). "Kick out the jams or get off the stand!" they'd taunt the out-of-towners; the phrase later became the title of the MC5's best-known song.

Even then, Fred was an iconoclast. Although he'd initially been taken by Eric Clapton's guitar work on the first Cream album, things had changed by the time the Five opened a Grande show for the Cream in early June 1968..

GARRY RASMUSSEN: They gave the Cream one dressing room, and on the other side of the stage was the other dressing room that the MC5 had. The Cream was taking solos, and they got to the point where Ginger Baker's playing his 10-minute, 15-minute drum solo, and Eric Clapton comes down into the dressing room, and Fred was pretty cool...he goes over to him and says, "Why don't you guys have a rhythm guitar player in your band?" "Well, we think that we can handle it without a rhythm guitar player." "Well, how come there's a rhythm guitar on your records, then?" Just giving him shit, basically. But that was the MC5, anyway. They kinda gave EVERYBODY a little bit of shit.

During a July gig at the Limber Loft in Leonard, Michigan, Sinclair was clubbed and maced by police following a dispute over money with the club's management. Hearing Sinclair's calls for help, Fred Smith rushed to his aid and was also arrested on charges of assaulting a police officer. The Five performed at the Yippie "Festival of Life" during the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago. They were signed to Elektra Records (for an advance of $20,000) on September 22, 1968, after Elektra's "house hippie," Danny Fields, witnessed a performance at the Fifth Dimension in Ann Arbor. Signed at the same time (for $5,000) were the Five's "little brother band," the (formerly Psychedelic) Stooges, the band formed by erstwhile blues drummer Jim Osterberg, now known as Iggy Pop, with the Asheton brothers - former Chosen Few bassist Ron on guitar, and Scott on drums.

SCOTT MORGAN: I knew Scott real well 'cause we had gone to Forsythe Junior High School, Scott and [his brother] Ron and I all went to the same junior high, when they had just moved here from Iowa, and we were all around the same age, and my dad had grown up in Iowa, so we connected fairly fast. Plus they were musicians. RON ASHETON: [My brother] borrowed (Scott's brother) Johnny Morgan's drumkit, so he had played a little bit. He had a basic idea of what to do, and he just sorta came along and learned, like we all did. He would go and hang out with Dave [Alexander] and the Morgans to some of their band practices, and he picked up a little stuff. He asked those guys, "Show me this, show me that." He'd watch them and then he'd emulate...he did know like the paradiddles and flamadiddles, 'cause he took drum lessons for a long time, and he did play drums in the band at school. He played snare drum.. But he pretty much learned how to play on the kit by himself.

Slightly younger than the Five and the Stooges, the Up were a band fronted by Trans-Love member and former Grande master of ceremonies Frank Bach and featuring the Rasmussen brothers, Bob on guitar and Gary on bass.

GARY RASMUSSEN: We were pretty influenced by the MC5. We'd been going to a lot of shows and playing a lot of shows all along, like the Yardley had a big show in the state fairgrounds in Detroit, which was like the Yardbirds, the Blues Magoos, Mitch Ryder & the Detroit Wheels, the Velvet Underground...quite a show, actually, for back then. After the British Invasion came through, we were actually playing a lot of songs by the Kinks and Yardbirds and that kind of music. Then we saw the MC5 play and since we were kinda hangin' out with 'em, we probably started buying bigger amplifiers and turnin' it up.

Recorded at the Grande on "Zenta New Year" (October 30-31, 1968) and released in early 1969, the Five's debut LP on Elektra, "Kick Out the Jams", stirred controversy from the word go, due to the use of the word "motherfucker" in Rob Tyner's spoken intro to the title track. The band agreed to record a "clean" version (substituting the phrase "brothers and sisters" for the offending epithet) for release as a single, which Elektra substituted on the album without the band's consent, removing John Sinclair's liner notes at the same time.

The Five were dropped from Elektra just six months after their original signing when they took out an ad in a Detroit underground paper blasting Hudson's department store for not stocking the record and prominently displaying Elektra's logo. Atlantic Records quickly signed the Five (for an advance of $60,000) and assigned former Rolling Stone scribe Jon Landau to produce their second album.

With Sinclair on his way to jail on a drug charge, Landau supplanted him as the Five's mentor. With almost no experience as a producer, and loathing what he considered the sloppy excess of "Kick Out the Jams", Landau committed the band to a program of playing simple arrangements "correctly," rather than extemporizing on every take, and set about "cleaning up" their recorded sound. The resultant album, Back In the U.S.A., wasn't really representative of the band, although it DID show the growth of their songwriting, particularly Fred Smith's. Following "Back In the U.S.A"., leadership of the band seemed to shift from Wayne to Fred.

MICHAEL DAVIS: Fred wasn't really into leadership in a formal way. Fred was only into having Fred's way, so he when it came time to really step on the gas, Fred wasn't there. Fred was probably the most slow-moving individual that's ever graced the Earth. Fred wouldn't move until Fred decided to move. There could be a forest fire six inches from your ass and if Fred wasn't ready to leave, nobody left. You weren't leavin'. I don't think the band rejected Wayne's leadership. I think he just stepped back to let Fred do some leading. The third album was Fred's concept, that was "Frederico Smithelini..."

Although that third album, High Time, hardly sold at all in its time, today it's the album which most fans agree was the Five's best. It's also the one where Fred had the most creative input as songwriter and "conceptualist."

DENNIS THOMPSON: It was the first record that we produced ourselves. We had a producer who was a "stable" producer for Atlantic, Geoff Haslam...But Geoff would sort of work with us and not tell us what to do, and let us sit behind the board and play with the dials and the mix, and let the whole group sort of work at it together, and then when it came down to a mix-down, we all would defer to Fred...let Fred and Wayne and Geoff do the mix. And finally we came up with a product that should have been released as our first one, 'cause that's pretty much how we played when the band started.

"High Time" is the record where Fred finally comes into his own as a songwriter and guitarist. He wrote four of the album's eight songs and played dual leads with Wayne on several tracks, most notably Dennis Thompson's "Gotta Keep Movin'."

DENNIS THOMPSON: I wrote ["Gotta Keep Movin'"] 'cause Fred could play really well, but see, Wayne was the flash, he would do most of the solos, and Fred held down the rhythm chords. 'Cause Fred was incredible in terms of rhythm and having an original feel to rhythm guitar playing. But he could also play lead like a badass sonofabitch. So I just made up my mind, "I'm gonna write a venue for Fred to show off his 32nd-note dexterity." I got together with Fred after I got an idea for it -- "Hey Fred, we're gonna do a real fast fuckin' song, and I want you to play that 32nd-note thing that you got down so pretty" -- 'cause him and I used to be pretty good friends. And we worked on it and put it together and then when we started doing it live, Wayne said, "I'm not gonna let that fucker show me up." So that's exactly what I wanted, was a battle of the two guitar players, and it turned out pretty damn fine.

Having alienated most of their American audience, the Five shifted their focus to Europe (where they had first appeared in 1970) By June 1972, after several tours of the Continent, Rob (who'd had a wife and children since '67 and was now unwilling to leave them) and Dennis (who was in a methadone program) had had enough. Both refused to go on the road again when another tour was offered.

DENNIS THOMPSON: [Fred and Wayne] did a tour as the MC5, but not with me, not with Rob and not with Michael. Fred and Wayne went over as the "MC2" and hired all pickup musicians [bassist Derek Hughes and an unknown drummer] in Europe. And they fell flat on their fuckin' face. They did three or four dates and they were back.

WAYNE KRAMER: Some of those gigs were just the worst. You'd arrive at the venue and the place would be packed. The promoter would be there, and he'd have his family and his children and want to meet everybody, and everyone was all smiles to have the MC5 here from America. The dressing room would be full of fruit and meats and cheeses and flowers and whiskey and wine and beer. Then we'd go out and play and of course, we were just fuckin' awful. It was just me and Fred and a drummer we hadn't even rehearsed with. He had no idea who we were or what our music was like. Fred and I had never even sung those songs before. We didn't hardly know the lyrics to them, and we'd go out and try to sing these tunes and play these parts.. Then of course you'd go back in the dressing room after the show and the flowers and the whiskey and the wine and the cheese and the fruit are all gone, and the promoter's gone, and there's nobody there to pay us. The crowd left the minute you started playing because it was so fuckin' awful. Then you'd have to go do it again tomorrow night - drive 500 kilometers in the snow to go through it again tomorrow night.

The bitter end came back at the Grande, New Year's Eve 1972. The band was paid $500. Wayne was strung out and couldn't finish the gig.

ASCENSION

DENNIS THOMPSON: After the MC5 broke up, about six months later, I was living in Detroit. Fred and Michael and myself got back together again, and we rehearsed in my attic in an old-fashioned two-story brick house, the old well-built ones. That's where we rehearsed, 'cause I lived in the upper fucking flat. Well, we put out the word to Rob, "Would you like to join our band?" And Rob declined. And we put the word out to Wayne, and Wayne declined. But we did make an attempt to put the band back together again. And the three of us were up there sweatin' our balls off in the middle of a hundred and twenty degrees because we all wanted to do it again. Everyone was free and clear of all drugs, all alcohol, nothing, we were completely ready to go again, okay? Rehab city, let's go. And they declined, so it never happened.

MICHAEL DAVIS: Ascension was Fred Smith's concept; it was gonna be Fred's band; he'd write the material and I would do the singing. There was some sort of mystique about me back in those days, that I could sing; it probably came from the [pre-MC5] folkie Bob Dylan-y thing, so everybody believed I could sing. So Fred thought that I would be able to do the singing and we went out and got me a little Casio [keyboard] so I would have something to do besides stand or leap around. We hired a dude named John Hefti to play the bass, and Dennis agreed to play the drums, and we thought we had us a little supergroup. It was Fred's compositions and Fred's idea to have this band. I don't think we played a lot of gigs, maybe two or three, and the kinda stuff we got as gigs wasn't anything that's gonna get you in Rolling Stone, like playing three or four sets a night in a bowling alley..."What? How'd we get here?" But I found out very quickly that if you have to use your voice for more than an hour and a half, you're looking at some trouble if you're not used to singing. So it didn't last a really long time, but it was a lot of fun...practicing in Dennis' attic and sweating our balls off up there in summer in Detroit.

SCOTT

The Rationals had also broken up, in 1970. Back in '68, they'd confounded their fans by following up a smooth soul ballad (Chuck Jackson's "I Need You") with a slice of guitar-driven psychedelic rock, "Guitar Army," a bona fide Michigan classic which provided a book title for John Sinclair and encapsulates the spirit of the time better than any other record save Bob Seger's "Heavy Music" or "Kick Out the Jams" itself. On their last legs, reduced to playing lounge gigs and shopping malls, they cut a classic album which was released on Bob Crewe's label moments before they sank without a trace. Since then, Scott Morgan had been playing R&B-flavored rock with a variety of bands including Guardian Angel and Lightning.

SCOTT MORGAN: This guy from Mainstream Records, Bob Shad, came out and he'd wanted to sign the Rationals. People advised us against signing with him. He had a bad reputation, so we DIDN'T sign with him, but after the band broke up, he came out, and he and Robin Seymour and I went to lunch. They were talking, and he mentioned, "Yeah, I wanna take you to Florida and record you with some session guys down there at Criteria." The Criteria house band [including Duane Allman on guitar] was really an awesome band, serious players, like the Muscle Shoals guys or the Stax guys...I don't know if that would have happened, but I got disillusioned at the meeting with their attitude, because I thought they weren't including me enough in the equation. They were kinda talking about me as a contract that was being passed around or something. [Ex-Rationals bassist] Terry [Trabandt] played with Mitch Ryder for a few months after the Rationals. Mitch had always wanted to play with the Rationals, and he hired Terry in the first incarnation of the Detroit band. After about six months, Terry quit and we started Guardian Angel. The first line-up was me and Terry and my brother David on drums, and [Wayne] "Tex" Gabriel, who we had met through Mitch. Tex moved to New York and joined a band called Elephant's Memory, which became the Plastic Ono Band, and we replaced him with an old friend of ours from Ann Arbor, Jeff Jones. Al Jacquez [ex-Savage Grace] joined the band, which was kind of a group thing that I wasn't really involved in, a group decision kind of a thing, but we started working with John Sinclair and Pete Andrews in a company called Rainbow Multimedia here in Ann Arbor.

Circumstances led Scott to team up with Fred Smith.

SCOTT MORGAN: When I initially started getting together with Fred, I intended to get together with Wayne [Kramer], because I knew Wayne a lot better. But Wayne steered me to Fred, and it was great! We became FAST friends, and hung out together all the time, had a lot of laughs and good times.. Y'know, we didn't have any money, but we shared the same interest in music, and it became a real close friendship there for a long time. I thought Fred was a great guy, very intelligent, very interesting personality, character, really funny, easygoing, laid-back...he was a lot like me; I don't mean to call myself intelligent, but I felt a kinship with him. We seemed to hit it off really well. We WERE a lot alike, so it was easy to become friends, and we did become really good friends and musical partners. So first of all, I played with Fred on guitar, Terry Trabandt wanted to be a guitar player, Michael Davis was on bass and [ex-Rational] Bill Figg was on drums and we did ONE GIG like that, and then it all fell apart.

MICHAEL DAVIS: That was the first incarnation of Sonic's Rendezvous Band. It was a name that Fred came up with as we were on our way to our first show. He said, "This is the name of the band. I wanna call it Sonic's Rendezvous Band" and everybody went, "Okay, Fred." When Fred said something, you just went, "Okay, Fred." And that was what that was. Later, we had this guy playing keyboard, James Allen. He was a relation to Jimmy Hoffa, nephew or something, and Fred thought that was good 'cause this was a connection to the real Detroit. Fred was real pleased at that fact and James Allen was actually a real good guy and a good keyboard player, and sort of a funny dude. I don't know whatever happened to him. We played at this place [the Limber Loft in Leonard, Michigan] where Fred and John Sinclair had gotten busted a couple of years before that for disturbing the peace and rioting. Morgan was somebody we all respected as a singer and his thing with the Rationals demanded a lot of "Respect," ha, ha; they were a good band. They never fucked up like we did. There was the Scott Morgan Group. One record that Fred and I played on, then Scott and Fred teamed up as Sonic's Rendezvous. I went to jail.

SPACE AGE BLUES

Michael's replacement on bass was W.R. (Ron) Cooke, who'd played with the band Detroit in both its original Mitch Ryder and later (former Amboy Dukes/future Cactus frontman) Rusty Day incarnations. In between, he'd had a spell in Cactus and a blues-based band called Catfish, led by Bob Hodge..

RON COOKE: My relationship with the MC5 and Fred and those guys goes back a long time in Detroit, I mean from when we were like 15 years old. When the MC5 weren't even the MC5, when they were hanging out in Lincoln Park, Michigan. I kinda went in and out of that scene with those guys for our entire musical lives, our entire lives, really. We grew up basically down on the lower southwest side of Detroit, in the suburbs, playing gigs and being in battles of the bands and all kinds of nuts things like back in '63 and shit. In Detroit, to a certain extent, it wasn't that it was cliquish, but there was a group of guys that kind of gravitated together.

About '73, '74, I had been out of the Detroit group for probably a year and a half, and I just wound up doing some gigs with some bar bands, just jamming around and doing that kind of stuff, and I got a call from Dennis Thompson and he had this thing he was putting together. I jumped on my motorcycle and rode back down to Detroit, and I met with Dennis and I think Fred was there. We kinda chewed this thing around a little bit, and I think we got together a couple of times and jammed, and then that thing kinda disposed and I got a call from Fred maybe like eight, nine months later, when Fred was living on the west side of Detroit.

This is the VERY BEGINNING, because Sonic's Rendezvous Band was me and Fred at the beginning, and that was it. No drummer, no nothing; me going down to Fred's house on the west side in the afternoon and jamming in the afternoon. Having tea, walking down the street, down to Michigan Avenue, going down to the bakery, coming back, smoking a bunch of cigarettes, drinking more tea, and jamming in the basement, and it progressed from there.

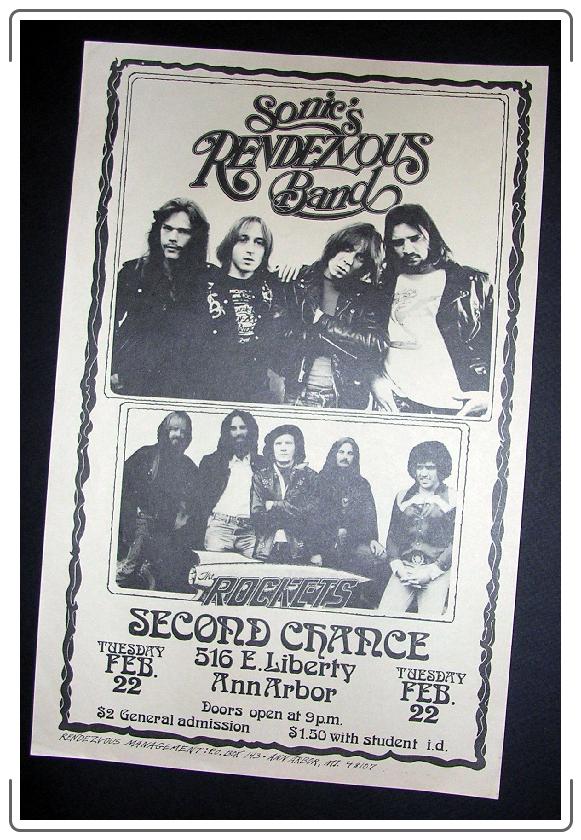

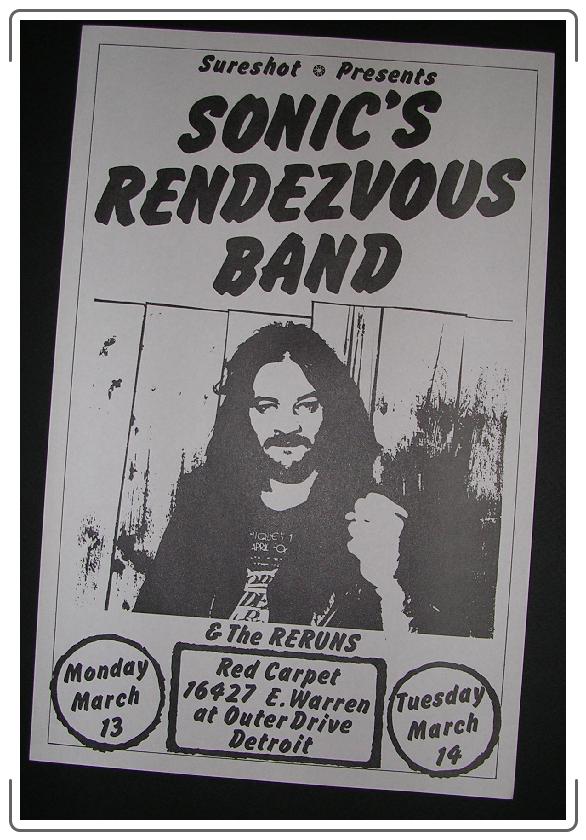

I got the first gig we ever did. I knew some hoodlums over on the east side of Detroit that had a bar, and we got in there and played a couple of nights in there. I think that we did some things at the old Miami, too...down on the Wayne State campus. For sure, we did a couple of things at the Second Chance in Ann Arbor, which was the premiere venue-type hall in Ann Arbor at the time.

[When I started playing with Fred], we didn't do any of the Five stuff, no covers. Really, the Fred thing and me was really a kind of a jazz-type rock improvisational jam thing. We laid out different parameters where we would go, and then we'd run in between and in and out of that. I do remember one song that Fred and me did compose together. It was called "The Grand River Subway." It was an instrumental jam and the premise of the jam - and it was a pretty funky thing - was to create a musical trip up Grand River Avenue out of Detroit, from downtown Detroit. Fred says, "Well, let's just think about...we're on a subway and we're starting off in downtown Detroit, and we're going to go all the way out through the suburbs with it." It was kind of a cool premise...it went from inner city funk, rock, blues, y'know, into the rock thing out in the suburban thing. It was a neat trip.

I've got two fabulous recordings, a studio session that I produced with Fred and John Badanjek from the Detroit Wheels. It's really some sweet stuff, man. I mean it's really some spaced-out stuff.

One song that Fred and Johnny B and me did together was "Space Age Blues," and then we've got this untitled instrumental thing that we did together that's not a rock tune at all, it's space city. Fred plays some of the FINEST guitar chords on this thing that you've ever heard in your life. It's a three-piece band but the way we recorded it, man, it's so WIDE, the sound of it.

I really enjoyed playing with Fred. Fred was not a real director -- he was but he wasn't really strong at it. Fred was the most relaxed character on Earth. He was like the opposite end of the world from me, personality-wise, but we had a rapport together. We were buddies, we had motorcycles and did a little riding and stuff down in Detroit, going to Greek Town and running around and hangin' out with some buddies of mine that were into the motorcycle/hot rod thing in Detroit. Harry Phillips was with us, the piano player out of the Detroit group. That whole thing went on for about three or four years, just kind of in and out of things, jamming a little bit and a couple of gigs. Then Fred got Scott Morgan involved in it, and then it took off a whole lot more after that, and it was a lot more serious kind of thing about it. We started rehearsing a lot and doing a lot of gigs.

SCOTT MORGAN: All these bands were breaking up around the same time, so there was all this talent around Detroit. I'd always liked Ron as a bass player, and we got to know each other really well, so he was a natural for me and apparently for Fred, because he went and played with Ron in the first incarnation of Sonic's Rendezvous Band, and it was just kind of a joke, I think; I don't think he was ever serious about the name. It was just sorta like, "Well, I'll just have this band, Sonic's Rendezvous Band, and we'll just play some gigs in a bar somewhere." Fred was driving a taxi, and he was living on the west side of Detroit with his wife Sigrid [Dobat], and he was doing this little lounge gig with Ron on bass and there was another drummer, I think it might have even been a revolving line-up.

Then Fred and I went to California for about a month. We drove out, drove a driveaway out and back. We were trying to cook up some business, because Detroit was never real strong on music BUSINESS. There wasn't any big-time movers and shakers here. There was one agency called the Diversified Management Agency, DMA, that was pretty big, but that was pretty much it, I think. So we were kinda looking for some connections. Networking, I guess.

We talked to this guy Bennett Glotzer, who was the business manager for Blood, Sweat and Tears. They had made me that offer that I COULD refuse [in 1968, to join the band, replacing Al Kooper], and I did. They called me back several times after that and made me offers, which I turned down. I think by the time that we got there, they'd heard enough...they weren't that interested. They were MILDLY interested; they said, "We'll find you a place to record if you wanna make some tapes for us, and maybe we can do something." But we didn't stick around. We stayed a few weeks and went back to Detroit. Terry Trabandt was living there [in L.A.], and his girlfriend moved back to Michigan, so he gave us his apartment. We were sleeping on the floor, we had a turntable, like a portable turntable, and we put that on the floor. We had a bunch of Beach Boys records; we just played Beach Boys all the time. Sleeping on the floor, had no furniture, no cooking utensils. It was really primitive.

I played this gig with Iggy and Ray Manzarek and James Williamson at the Hollywood Palladium. See, James Williamson lived in the same building, the Coronet on Sunset and La Cienaga, right next door to the Hyatt and the Comedy Store. It's something else now...expensive condos. I was playing harmonica. Iggy asked me to play harmonica, and on the day of the gig, I locked the harmonicas in the room, and they had come to pick me up. So Iggy went out onto the balcony and jumped from one balcony over to my balcony to go in and get my harmonicas! We're on the third floor, and I'm going, Whoa! This guy is OUT THERE! He's really dedicated! "I'LL get 'em!" And we're going, "Oh, my God," and it was so bad.

After the gig, I didn't have the key to get into the room, so I kicked the door in, and that's why we had to leave. The reason I kicked the door in was because the person across the hall had gone and was locked out of their apartment, and they tried to go through the air shaft and fell four stories into the basement! So this girl who lived there, whose roommate had fallen, had forgotten HER keys and she was gonna do the same thing...she was gonna crawl into the kitchen window across the air shaft, and Fred kicked HER door in. The whole thing was insane!

Back in Michigan, Smith and Morgan linked up and prepared to re-enter the band wars.

SCOTT MORGAN: When Fred and I decided to try it again, we kept the name [Sonic's Rendezvous Band]; I said, "I LIKE that name!" He didn't like the name; he thought that it should be a BAND name, not have his name involved. He wanted to call it the Orchids. And so we did, for one gig, and there was a blizzard. We had rented this ballroom at the Detroit Cadillac Hotel and NO ONE showed up, 'cause there was a huge blizzard. We had rented a P.A. and hired a local deejay Dan Carlisle to spin records, and we had hired Terry Trabandt to play bass, I think Jeff Vail was playing drums at that time, and Jerry Hopkins, a saxophone player was playing with us. And NO ONE showed up. There was a poster made up; Fred's manager Chato Hill made this poster up, and I still have the poster, but we decided after that gig that it was not to be...we should keep the Rendezvous Band name! It was cursed! It was DESTINY! After that, Terry got out of the picture, and Ron [Cooke] came back on board. Jeff Vail stayed around for a SHORT time, not too long. We had another drummer for awhile, Mike Martinez, for a little bit, but that didn't last very long either.

GARY AND ROCK

It was Scott Morgan's idea to bring in ex-Stooge Scott "Rock Action" Asheton on drums.

SCOTT MORGAN: We figured since Scott was no longer with the Stooges and we needed a drummer, we should get him in the band. He didn't have any drums. After the Stooges broke up in Los Angeles, he had stayed there, and he was staying in Ron [Asheton]'s apartment, which was also at the Coronet, the same hotel where James and I were staying. A friend of mine, Doug Curry, was James Williamson's roommate, and Ron had another apartment, and Jimmy Recca [ex-Stooges bass player] was staying there off and on, and Dennis Thompson was staying with Ron, I think...they had a band [New Order] in Los Angeles. Scott had nothing but his drums, and he was sleeping on Ron's floor behind a chair, and he sold his drums to Dennis for a plane ticket back to Michigan, so he had no drums. He came back, he had NOTHING to show for the Stooges, and was just sort of hanging around.

RON COOKE: When Scott [Asheton] came in, that's when it appeared that Fred was trying to come out of his basement. To try to get Fred to get out and go do a gig was like pulling teeth! Oh, yeah. Where he got the name "Sonic" from, I don't know. That was like the opposite end of the world. So when Scott got in the group, Fred Brooks got hooked up with Fred, and Brooks started to try to put some gigs together. We weren't actively out trying to get gigs. For Fred to cut a deal with somebody to go out and say, "Hey, get us a gig" - that's six to eight WEEKS of negotiations, and there's nothing there to negotiate, y'know what I mean? So I guess Brooks started getting us some gigs, and that's when Scott came in and we played a few gigs.

One fan who witnessed many Rendezvous performances was Deniz Tek, an Ann Arbor native who'd carried the gospel of the Five and the Stooges to Sydney, Australia, where he was attending medical school. In the mid-seventies, Deniz and his band Radio Birdman were remaking Australian rock in the high-energy image of late-sixties Detroit.

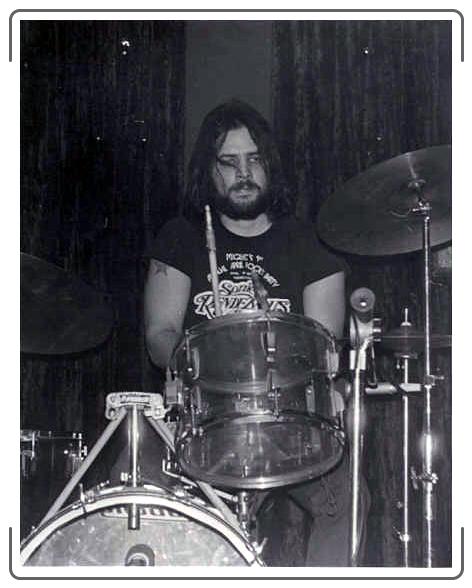

DENIZ TEK: One of the things that I felt was the best about that band, the thing that defined it, was Scott [Asheton] on the drums, because he hit the kit SO HARD it'd shake the room. You would not think that any drum fittings could be made [that were] good enough to withstand that kind of punishment. He was like that. He had a very simple kit; he always had Ludwigs, snare, one rack tom, one floor tom, hi-hat, crash, ride, and the bass drum - that was all. But he was just WHACKIN' them, with PERFECT time, and just driving like a big train - it was awesome!

The last piece of the puzzle fell into place because of Ron Cooke's affinity for motorcycles and his inability to get along with Scott Asheton. Gary Rasmussen had just left Uprising, the band which evolved out of the Up.

GARY RASMUSSEN: I had gotten fired from Uprising, and I was really looking for work, going to Detroit a lot and hooking up with different musicians, trying to put bands together. At that time, it seemed like everyone I would hook up with, there was always some reason it wasn't really happening.

RON COOKE: Rasmussen? Gary's a good player, he's a good dude, I've known the guy a long time. He's become a really good player over the years.

The Sonic's Rendezvous thing, I guess we went in and out of that thing for a year and a half, two years. Then I guess other things caught my mind, I was doing other things in my life. I'm the kind of guy that if I was involved in something, sometimes it wasn't always the best thing for me...I really got gung-ho on some of these things. As far as me goin' in and out of the band...if you're not enjoyin' what you're doin', you don't do it anymore.

SCOTT MORGAN: Ron's a biker, he's a Harley guy, and he was riding with this group called God's Children, who had been security for the Stooges, and he kept selling his guitar and buying a new motorcycle. He kept goin' back and forth -- "Oh, I'm gonna sell my guitar and buy a bike!" And then he would borrow Gary's [equipment]. Scott and I had been hanging out with Gary. We wanted Gary in the band. Scott and Ron didn't get along. Ron and I got along pretty well, but Scott and Ron are two fire signs and they were always at each other. So we thought Gary'd be a good sub for Ron. We'd known Gary from the Up, we were old friends and stuff.

GARY RASMUSSEN: Ron Cooke was coming to my house and wanting to borrow my equipment, because he'd pawn his bass and buy a motorcycle, and he wouldn't have any equipment. So then he'd come to me and want to borrow my stuff, and I think I did actually loan him things a few times, but I didn't really wanna be doing that. Here's my stuff, and here's this guy going off playing, although I knew all those guys, it wasn't something I felt great about.

SCOTT MORGAN: The last time he did it, we had this gig in Bad Ax, Michigan -- it was like an outdoor festival -- so we were gettin' ready for the gig, it was just a few days away, and Ron calls and says, "Hey, can you find me a BASS? I sold my bass to buy a new bike." So Fred just got fed up.. [Ron] tells me that, and I'm goin', "You better talk to Fred." This is at my parents' house, and I hand the phone to Fred and I'm goin', "You gotta talk to Ron." So he gets on the phone and he's going, "Yeah. Mmm-hmm. Okay." Turns around and says, "What's Gary's number?"

GARY RASMUSSEN: I think part of it might be because Ron Cooke was used to playing with Johnny Bee, and Johnny Bee is like a monster -- STILL one of the greatest drummers in the world. But Ron Cooke and Scott Asheton didn't get along really, so I think it was really Scott Asheton and Scott Morgan [who] started telling Fred, "We should just get Gary to play." So Fred called me up one day and said, "What are you doing next weekend?" and I said, "Nothin'. Why, what's goin' on?" He said, "Well, I'll send over a tape and we got this gig next weekend if you can do it." So he sent me a tape and that was the beginning! Playing in Bad Ax, Michigan -- it's up in the "thumb." That was 1976...I think spring of '76.

SCOTT MORGAN: So we called him and he rehearsed with us and did the gig, and it was a great gig! Went really well, people loved us, sounded good, and there was a big crowd there, so we figured this is definitely...he was in the band! From there on out.

GARY RASMUSSEN: We were playing bar gigs, and not all that many, especially at first. Maybe some friends would have a party, or a few clubs that would hire us once in a while, we'd get some club somewhere, and a lot of times when we'd go to play, the reaction we were getting was NOT "Oh, this is the greatest band in the world!" It'd be more like people goin' "What the HELL is THIS? It sure is LOUD!"

I SEE THE PARTY LIGHTS

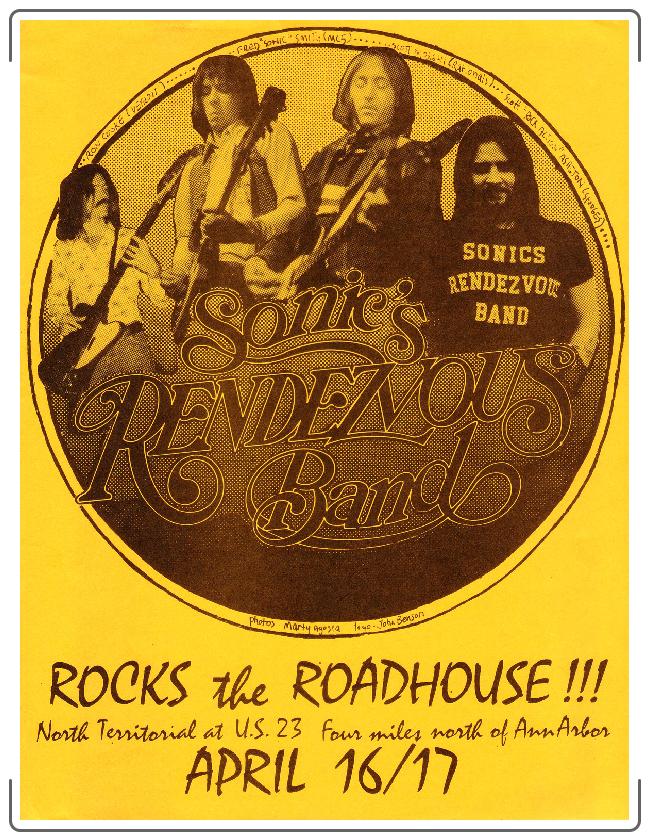

DENIZ TEK: A lot of the times I saw them, they were in small towns in Michigan, sometimes even very rural, not even in a town, but in a roadhouse or a bar which I think some people would consider to be redneck-type bars, and they'd be playing. I think the first time I saw 'em was '76...maybe really late '75 or early '76; it was that winter. They were playing at the Roadhouse, which was one of those kind of bars that I was talking about before, at Whitmore Lake, which is about 10 miles or so north of Ann Arbor. Ten or 15 miles, it's up U.S. 23, and get off the freeway and it's just this bar and grill. You would not expect there to be a good band in there. My brother and I were out at a student bar, drinking beer and talking, and we happened to see an advertisement for that show. It was already pretty late, and the band would've already started, but we got in my brother's car and drove up there just to check it out 'cause the roster was so great! Scott Morgan, Fred Smith, Scott Asheton, Gary Rasmussen...I had no idea they were playing together until I saw that advertisement. Went up there, went in there, got there in the middle of their set and the music blew the top of my head off. It was incredible!

I had left at a pretty good time (I left Michigan in '71) and then I came back briefly in '72 or 3, and there was nothing happening musically, and then when I came back in '76, there was nothing happening at all. I didn't see any good bands I really liked. There was nothing going on, nothing to compare with what we were doing in Sydney [with Radio Birdman] until I saw these guys, and it was like life was breathed into me, and [here was] a new source of energy and raw material and learning that I could tap into, that I hadn't had for so long. I really felt isolated before that, but then when I saw those guys, I thought, "Wow, this is where the stream of real music has gone. Sometimes it goes below the surface of the ground, and comes up somewhere else, and you never know where it's going to reappear." And there it was. It hadn't died out, and it just made me so happy. I usually never dance at a gig, I just sit in the back and watch. But I had to dance; I was dancing. I couldn't stop myself from doing it!

SCOTT MORGAN: Cover bands were all getting the money. There were some bands who had major record deals, like the Ramones, Patti Smith, and Cheap Trick, and they had big-time management and booking, and major record labels, and they could do pretty well, but we were just one of the local bands playing original music and there just wasn't much of a market for it, so we had a hard time working and making much money.

DENIZ TEK: When I saw these guys, the rest of Michigan was a wasteland...In Michigan, the Five and the Stooges weren't the big deal that they are in Paris or Berlin or somewhere like that. When they were going, when I was a junior and a senior in high school, the MC5 were fairly well respected because they had a hit with "Kick Out the Jams," and everybody heard it on the radio. They were NEVER afforded the respect of Bob Seger or Ted Nugent or any of these other guys. They were just sort of regarded as these radicals that played music and had wild shows, but most of the average people in Michigan wouldn't really know about it. And the Stooges were even much less respected than the MC5. In those days, they were considered lunatics or a joke. They were regarded by the kids in my school as too strange to even think about.

You have to realize that in Ann Arbor, Michigan, most of the town is students...50 to 60,000 students and about an equal number of residents, and most of the residents are not particularly interested in music, and the students are, but the students only come for four years, then they go away.. So the students that were there in '76 weren't the ones that were there in '68, and this new crop of students comes in and they don't know the Five or the Stooges from a hole in the ground, 'cause those were a local phenomenon in both place and in time. So no, I don't think their reputation worked either against or for them. It probably didn't make any difference at all, except to attract a few hardcore people who would know about it, like me.

GARY RASMUSSEN: If they DID know who the guys were and what we were doin', a lot of people wanted us to play MC5 tunes, or play Stooges tunes, or play Rationals tunes. And we pretty much decided (I think MOST of that came from Fred) -- that's not what we're about; that's what we WERE, and this is something different. We're doing what we're doing NOW! Fred was writing songs, and Scott was writing songs, and the band would get together and we'd work 'em out, and that's what we were doing!

SCOTT MORGAN: The ground rule that Fred and I set at the beginning, and it was mostly Fred's idea, but I agreed with it, [was] that we would not do any Rationals or MC5 songs...or Stooges, once Scott was in the band, or Mitch Ryder songs with Ron, or Catfish songs. Starting a clean slate, and anything we covered would just be some obscure R&B tune...that was part of our M.O. Everybody would pick out an obscure R&B tune like "Ramblin' Rose" or something like that to cover.

GARY RASMUSSEN: We weren't covering any of OUR old songs, so if we did a cover tune, it'd be something different, something that we liked. But of course, if we had played the stuff that people wanted us to play, we would have worked more, and probably made more money. On the other hand, we wouldn't have gotten all the songs together that we ended up having, because the focus was on what we were trying to do THEN, not on what we had done before.

SCOTT MORGAN: When we first started out, we actually did a LOT of stuff, because didn't have a whole lot of original material...not our own stuff, but lots of other covers. Like Fred sang "Help Me, Rhonda;" I sang "Mama Roux" from Dr. John. We did a lot of R&B covers; we did "I Put A Spell On You," "Harlem Shuffle," stuff like that. It wasn't like we were covering the current hits. Fred did a cover of one of the songs from the first Who album. He liked the Who, he liked the Stones, he was a huge Chuck Berry fan. We all liked the same kind of music. "Party Lights" was just an obscure tune that we grew up with, that was on the radio when we were in junior high or something like that. Claudine Clark; it was the flip side of the record, and somebody flipped it over, and it's like whoa! Pretty cool song.

DENIZ TEK: They were doing quite a few covers. As far as originals, they were doing "Dangerous" and a couple of things like that, that era, and they were doing "Like a Rolling Stone" and "Party Lights," they were doing "Sweet Little Sixteen," songs like that. Fred was singing all those covers. I got the impression that he really was into that kind of music - he must be a deep fan of rock'n'roll, because he was playing those songs great, and singing them like a guitar player would sing them; he had a guitar player's voice. Not a great singing voice, but somehow it was real true, 'cause he wasn't thinking about singing while he was doing it; he was thinking about playing the guitar. And singing is a side effect, so it comes out real true and honest from guys who actually are not thinking about it.

He had a couple of Marshalls...maybe one Marshall cabinet, 4 x 12, and it looked like he was driving it from a Fender Twin; he had a Fender Twin sitting on top of it. I didn't see a Marshall amp. He had his Rickenbacker 450 12-string; no Mosrite, just that Rickenbacker. That's the only guitar I saw him play in that band. He told me that he would listen to jazz saxophone players and try to figure out their solos on the guitar. He'd sit for hours and do that, and I think that might be one of the keys to his technique...originality. Nobody really plays like that! He used to put the pauses in where guys'd take a breath, and I think that's part of it.

Scott played, almost exclusively, chords and rhythm guitar. He would occasionally do a lick, but it was rare. He had a Telecaster or a Broadcaster, something like that. It all worked really well. They occupied different portions of the frequency spectrum. Fred was much more low-mid and smooth sustain, and Scott was more jangly and trebly, Telecaster-type sound.

They did [play larger venues] later on, but at the time, Fred had cowboy boots that were held together with duct tape! They were poor and they were lucky to get drinks and lucky to get a gig where they could make 50 or a hundred bucks, that was what they were getting. They were not appreciated that much locally. I wondered, "How many people in this room know what it is that they're seeing and hearing...know what the quality of it is?" There probably weren't that many at that early stage. But then I went back to Australia and I came back to America, and they were playing bigger shows. They were playing at the Second Chance, which was a pretty big club in Ann Arbor, probably at that time the biggest rock club to play, and they pulled big crowds there, so they had sort of broken through...people had found out.

GARY RASMUSSEN: You keep playing and after awhile, you start developing something. We used to play the Second Chance Bar in Ann Arbor, and we'd tend to do that on Sunday and Monday nights, which are the really off nights of the week to play, but we started having a pretty hardcore fan following. People either hated us or loved us, so it seemed like there'd be a group of people who thought we were the best thing EVER. But it's a small group, y'know, and we were playing Sundays and Mondays there because we were drawing 200 to 300 people into the bar on a Monday night, and we'd ask, "Why don't ya give us a weekend?" And the guy would say, "Well, ANYBODY can fill my room on a weekend!" So we'd get a Monday, where we could put 300 people into his bar. It makes sense from his side.

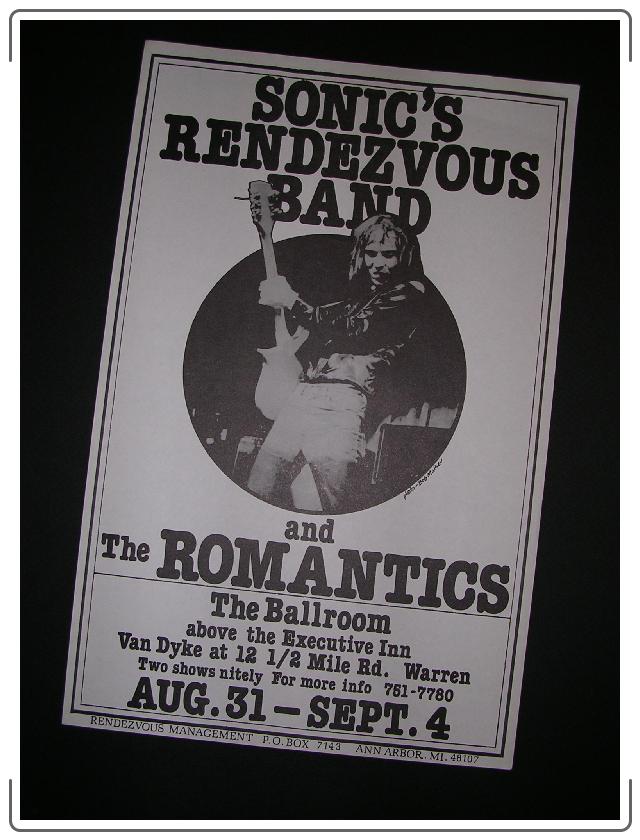

SCOTT MORGAN: [We] played a lot at the Second Chance; that was our home gig...Chances Are, then it was the Second Chance, then it was just the Chance, and now it's the Nectarine Ballroom; it's a dance club now. That was our house gig; we were there every couple of months on a Sunday, Monday, Tuesday; on their off nights. They had like cover bands that would come in and play four nights a week. And then they had some headliners come in, like the Ramones, Cheap Trick, and Patti Smith. Yeah, they had a lot of people coming through there: Emmylou Harris, James Brown played there, Jerry Lee Lewis, all different kinds of people, but for the rock bands, they would hire us to open the show, and then they'd give us the really crummy off nights, like a Tuesday night, to fill the room up, and then they'd give these Top 40 bands four nights and guarantee 'em two thousand bucks or something like that. It was really kind of a drag.

And then we'd play anywhere else we could. We played in Detroit at Bookie's. We played a club out in the middle of nowhere, and we had like two or three nights booked, and NOBODY was there. Just this little redneck bar in the middle of nowhere, southeastern Michigan, down towards Toledo, and the Dictators walked in one night! They were playing in Toledo, and all these guys came in and it's like, whoah! There was like two people sitting at the bar, and we're there, and it was really cool. They'd heard that we were playing, so they drove all the way up from Toledo, which is like 30 miles or something.

SONIC AND SCOTT

Initially, Scott provided most of the original material, but as Fred started to write more, competition between the two frontmen began to emerge.

SCOTT MORGAN: The way it boiled down was, Fred would sing his songs and I would sing my songs. We tried to write songs together, but just never got off the ground with it. We were each writing our own songs, and it was kind of like an inspirational thing, like Fred would write a new song, then I would write a new song, and then HE'D write a new song, and we kind of inspired each other to be more creative and try something different next time. Our own sound was fresh and progressive. He started writing more and more songs, and that meant that he was singing more songs. I don't think it was initially a conscious decision.

GARY RASMUSSEN: They weren't fighting. It was maybe an unspoken rivalry, in a way. We ALWAYS rehearsed. That's the one thing; we always rehearsed whether we had gigs or not, or anything. We'd get together and play, more than anything. And when Fred would show up with a new song and we'd work on that, then the next week, maybe BECAUSE Fred showed up with a new song, then Scott would show up with a new song. Maybe because Scott did, then the next week, Fred would show up with TWO new songs. It was kinda goin' back and forth like that. I think they were driving each other in a silent way, without ever...I don't think they ever talked about it.

I thought it was actually great, y'know. I didn't really lean one way or another, "Let's do all this or all that." I thought it drove both of them.. I don't think either of them ever wanted it to get to the point where they were doing all the other guy's songs. So they were pretty much pushing each other, although they never talked about it. I think it WAS a good thing.

SCOTT MORGAN: I think Fred always DID want to be a frontman, but I don't think he had the confidence to do it when we first started. I think he realized that I should be the singer, he should be the lead guitar player, which is pretty much the way it started out. But it kind of evolved over five years into a situation where he was writing more and more songs and singing more and more songs, and I'm getting kind of like pushed out of the picture, as far as a singer goes.

In the '76 to '78 period, it was like that, and it was really healthy and it worked really well. And we each had about half the tunes, but as it got more and more Fred and less me, it started getting unbalanced. Like the two [Mack Aborn] records..."Sweet Nothing" was May '78, and that was right at the peak of when we had the perfect balance, it was about half each of our songs, maybe Fred was singing one more than me, but it was fairly well balanced. We never counted that way; we never said, "Well, you sing EXACTLY half and I'll sing EXACTLY half," but when it was about at that period, it seemed to be the strongest. Later on Fred started getting a little more eccentric, I think, and he wanted to try different stuff.

GARY RASMUSSEN: In a lot of ways, it was Fred's band, not because it was like "this is FRED'S band," not like that, but more like when you're trying to work, especially in a band, you're working with all these people...Fred was an odd guy. Not a bogue guy or nothin', but as it turned out, if Fred didn't wanna do it, it wouldn't happen, basically.

Fred would call up and he'd want to know what you felt about everything. "Okay, what do you think about this?" "Well, I think this and this," and you'd talk. "What do you feel about this?" And you'd talk about that. And then you'd say, "Well, Fred, what do YOU think about this?" And he wouldn't really say. He'd go, "Well, y'know, whatever, I've gotta go now." So Fred was always a mysterious kind of a force.

So in a way, I think he kind of led the thing just by being the way that he was. He'd get everyone's opinion on everything, and then he would kinda decide what HE would do. If he wasn't into doing it, we wouldn't do it, because you couldn't persuade him to do anything that he wasn't into doing, whether it meant money or anything. He kinda had his vision of what things were. But it wasn't like we were fighting all the time with him, either. Like I said, he'd want to know everything you thought about everything, but he wouldn't really give up too much of what HE was thinking.

I think he came into his own or something, kinda realized that he could really do this. With that group of people, too. We certainly allowed him to do whatever he wanted to do. And that band evolved totally from the beginning to the end, too. Because when I started with the band, we probably did three quarters Scott Morgan songs and a quarter of Fred's songs. When I thought the band was the best, we were doing about half and half, Scott's and Fred's, and it went on [until] by the end, we were probably doing three quarters Fred's songs, and a quarter Scott's songs.

DENIZ TEK: I never talked to Fred about it, but the other guys told me that Fred was an extreme perfectionist, and he was never satisfied, and they did actually attempt to record (or start recording) more songs, but Fred would cancel it because it wasn't going the way he wanted to. He would only have it a certain way and apparently those two songs were the only ones that were working out to his satisfaction. Stereo and mono version of the same song on two sides of a vinyl 45...it'd be nice if there was more! But in a way, it makes it even more special. I think that the Freddie Brooks and Bill Lord CDs are an excellent document of the band...better than I ever expected to find.

Fred was real reclusive. He would just sit there in the dressing room with those guys, and he'd be smoking a cigarette and having a drink, and say nothing. He would occasionally say one or two words to me and smile a little bit, and people later would say, "Wow, he must like you a lot 'cause he said so much to you!" And of course, Scotty Asheton, when you first see him, he's real intimidating, and he doesn't say anything either until you get to know him. So you've got two guys who are stone-faced and intimidating-type characters - I never thought Fred was that intimidating, but Scotty appeared to be dangerous when I first met him. He's NOT; he's real gentle, actually. Scott Morgan, on the other hand, was more willing to talk. He's more of a conversationalist.

"HILL & BROOKS"

Management of the band was handled by Chato Hill, a Vietnam veteran, and Freddie Brooks, a native of Cleburne, Texas, who'd had a White Panther chapter in Fort Worth (their office was next door to Joe Nick Patoski's record store) before police harassment led him to flee to Ann Arbor in 1969. Freddie had been staying with Scott Morgan at Scott's parents' house.

SCOTT MORGAN: Chato [Hill] was Fred's manager, and when Fred and I started working together, Chato naturally became THE MANAGER, because I didn't have a manager. He was managing Sonic's Rendezvous Band. Freddie [Brooks] and I had worked together trying to do something out here in Ann Arbor, forming my own band; Freddie had helped me a little bit with that. So, I brought Freddie into the picture, basically, but once he was IN, he became like Fred's guy.

We tried to hook up Chato and Freddie, call it "Hill & Brooks Management" - 'cause we thought "Hill & Brooks" sounded real pastoral. They weren't goin' for it; they were like oil and water, it just wasn't gonna work, so at that point, Chato became like the "executive manager" and Freddie was like the "working manager," the guy who did all the day-to-day stuff. Chato was like the overseer, the guy who put up the money for us to record "City Slang" -- basically he was like our backer, and Freddie did all the legwork. He did all the booking, and the posters, and roadie-ing, and all that stuff.

It was kind of a watershed period, because "City Slang" came out, and at the time we were putting out our first single, which was a great record, the inner dynamics of the band were changing in a negative way. There was all this acrimony between me and Fred, and it started sending us on a downhill slide that we never recovered from.

THE GODFATHER OF PUNK

SCOTT MORGAN: I think that the idea was that we would put this single out and then we would get a record deal, but for some reason, it just didn't pan out that way. I dunno. Everything was cookin' on all eight cylinders there: we recorded "City Slang" and "Electrophonic Tonic," we had a really good two-sided record there. We shoulda released that. They probably shoulda never gone to Europe with Iggy, and would have been entirely different. But that's not the way it worked out. Somehow we got derailed around that period, and we never got back on track. It was just a combination of things. If Fred and I had kept the same dynamic where we were sharing the singing duties and the writing duties, we may have gone on.

GARY RASMUSSEN: I think at that time, [Iggy] was having trouble with his record company. He'd been a mess, screwin' up, and he pretty much needed to prove to the record company that he could do a good tour with a good band - it had to be somethin' special - and that he wasn't just a total junkie and all that stuff. He called up and was talking to Scott Asheton to start with, and then to Fred. We knew Iggy because he'd come through with his band and we'd go see 'em, and we'd be playing some awful place down in Detroit, in Cass Corridor or somewhere, and Iggy would be playing at the Masonic Temple; he'd come to our gig after, y'know, and come up onstage. We were all friends.

So at that point, I think he needed something like that, and asked if we would do that - come and do a tour with him and be his band. Scott Thurston was in that band...Scott was already with Iggy, so he knew all of the songs that Iggy was doing, he knew kinda what was going on, so I think Iggy wanted to keep Scott Thurston in on it, so he didn't need Morgan, basically. You don't need another singer...if you ever tried to harmonize with Iggy, you'd realize it's a pretty hard thing to do. But we didn't need another singer, we didn't need another guitar player, so Scott was kinda left out of that one.

SCOTT MORGAN: When they were first offered the job, Fred's going, "I don't think I should go, I don't think I should go," and I'm going, "GO! Come back and the record'll be out and we'll pick up where we left off." Because I was the only one who was not offered a position in this band. So I'm here, and Freddie [Brooks]'s still here, and Chato's here, so we're workin' on getting the record released while they're over there.

In the meantime, this friend of mine wants to take me in the studio and record a couple of songs. So what the hell, those guys are in Europe for six weeks, why not? It wasn't to release; it was just for kicks. We did a ballad called "Satisfying Love," and we did a version of "Cool Breeze." That was with Ron Asheton, and Harry Phillips, who played with Catfish, and Steve Dansby, a local guitar player who's really great. We never released it. We never INTENDED to release it. That's why I felt it was unfair for Fred to tell me that I had to sit here and wait and twiddle my thumbs while they were touring Europe.

GARY RASMUSSEN: We did pretty well. It was all right. [Iggy] was paying us well. RCA Records was covering everything, and we had a bus and equipment people and lights and the whole deal. In '78, Iggy was big in Europe. We were playing in theaters and outdoor venues. Nice shows, really. He was the headliner. "The Godfather of Punk."

In London, the band had a visit from Deniz Tek, then touring Europe with Radio Birdman.

DENIZ TEK: Fred and I could talk guitars, and I guess that kind of broke the ice, because I had his old guitar, and he was real interested in that.. He offered to buy it back when we were in England. He was over there; the Rendezvous Band minus Morgan was backing Iggy Pop, so we went out to dinner with them and stuff like that, and then we went to their gig at the Music Machine in London. I think we dropped by the soundcheck in the afternoon because Fred had asked to see the guitar.

GARY RASMUSSEN: In Norway, I think there's a city called Orbro, I'm not exactly sure, at an outside festival, kind of sick situation, Iggy was the headliner, and outside, maybe three or four thousand people there. Didn't know it at the time, but found out later that there was some kind of a Norwegian organization of "Fascists Against Punk Music" or something like that. They were organized, a small percentage of the crowd. It coulda been five guys or six people or something. We went up to start playing and right in the first song, these FISH are coming up. Somebody's throwing fish, these herrings. They come up and smack you on the bass or something, these fucking herrings. And you look at each other going "What the hell is this?"

And Iggy is like...it don't take much. He starts sticking his ass out at the audience, "Hey, FUCK YOU, man, fuck you," sticking his ass out, and then people are throwing...it started out fish, and then it turned into OTHER stuff. I saw something coming through one of the big spotlights, you could see shit coming through the big beam of light, and I just caught it between my bass and my shirt, and it was a broken bottle, and it cut the button off my shirt. And I said, "I'm done!" and walked back, I turned my shit off and walked off. Finished! Not worth dyin' about. And at that point, I think 99% of the people there were there to come see the music, and they got pissed off, and they were finding the people that were throwin' stuff and beating the crap out of them. It was kinda like a mini little riot goin' on, so I just stayed backstage, but there was a lot of roadies and security people walking around with big hunks of wood and stuff. But we never did go back out and play. No way! We found out later that in that country, if somebody sends you fish like that, you got a herring on your doorstep, that's supposed to mean something. "Leave or die" or something like that.

SCOTT MORGAN: I think that [Iggy] really wanted them to give up Sonic's Rendezvous Band and become his backup band and tour the world with him. Well, they did a six week tour of Europe, and then Iggy said, "Now let's do the States," and Fred said, "No, we're done." And there was a little acrimonious, misunderstanding kinda breakup there.

The Holy Grail: The greatest single ever pressed.

GARY RASMUSSEN: At the time, when we were in Europe doing the tour, actually the "City Slang" record was being pressed here in the States, and Fred had met Patti, and just the timing of everything... Fred had met Patti already, and I think they were deep in love. Fred probably spent all the money we made over there on the telephone talkin' to Patti! He'd be on the phone for HOURS from somewhere. I don't think money really mattered that much to him. I think Fred wanted to come home and see Patti, because it was the beginning of their thing, and we were all thinking really that we've got a record coming out...we kinda thought that this was gonna be something big for us, too. And to tell you the truth, after three months in Europe, doing that kind of a thing, we were exhausted. Hadn't quite figured out yet that you couldn't drink and everything that was there and do everything that showed up! It takes awhile before you realize, "Hey, you know what? You CAN'T do all of it!"

So after three months of that, we were tired! I think everyone was ready to come home. It wasn't really 'til the end of it that Iggy started saying, "You know what? This is a great thing, and it's a great band, and we could take over the world. We could go do Japan, and we could do this and that." Actually, David Bowie was at the last couple of gigs that we did, 'cause like the last gigs we did were in London. He came to the show and he seemed to think we were really quite a powerful band. He invited us, instead of going home, to come with him to, I think he was playing in Glasgow or someplace. I think it was the timing of it, by that time we were all thinking, "God, it's time to go home." Personally I was thinking, "Yeah, let's go!" But I think the other guys were pretty whipped, and it didn't take too much for me to go, "Yeah, okay, I'm ready to go home, too."

Fred and Patti

SCOTT MORGAN: When Fred got back, he just went through the roof that I had recorded while they were over there. I'm going, "Well, this seems a little UNFAIR! You guys just went on a six-week European tour and left me here, and you're all upset that I went in and recorded two DEMOS, not for the purpose of trying to get a record deal for myself, just for the hell of it!" So we had a big falling out about that, and finally I just got mad and said, "I don't want my song on the record." It was just one of those stupid things. It just gets out of hand, and you wish you could change it, but it's too late.

"Electrophonic Tonic" was WRITTEN to be the show opener. Because of the way the songs starts with a big power chord, and then it sorta like winds up until it's full-blast. "City Slang" was supposed to be the show closer; it ends in a big jam-out, rave-up thing at the end. I had the opener and Fred had the closer, but then I lost the opener!

I had recorded "Electrophonic Tonic" in the basement with Fred and Ron Cooke and Scott Asheton, VERY early on in the Rendezvous Band, in my parents' basement. And I told Fred that I liked THAT version better than the one that was coming out on the record, and THAT didn't help. Finally, we just said, well, let's put out "City Slang." We'll just make it a demo, and we'll find some other song to put on the flip side. We'll make it like a promotional copy -- stereo on one side, mono on the other. Well, we never DID find another song...and the other song was gonna be another FRED song, and THAT didn't help, either.

That just unbalanced things even more.

I think at that point Fred had decided that HE was gonna be Sonic's Rendezvous Band, and it was time for me to move away from the center of the stage. Plus he and Patti had started seeing each other around that time, and that changed his way of thinking also. I think she encouraged him a lot, which was GOOD, because I think he had a LOT of stage presence. You could see that from the MC5. He looked really good, he was good at talking to the audience, stuff like that. But his HEALTHY ego...as far as the dynamic between Fred and I, it started getting unhealthy for OUR dynamic.

GARY RASMUSSEN: We got back from the Iggy tour, and we were doin' some gigs with Patti, opening up for her. Not a lot of them, but I think we did the Agora Ballroom in Cleveland and the Avalon in Chicago, the Masonic Temple in Detroit. Really kinda nice places to play, and we were just opening up for them. Patti was really quite popular at that point.

SCOTT MORGAN: Actually, Patti wanted us to open for her on more dates! We did three dates with her: Chicago, Detroit, and Cleveland. And I think Fred didn't want to do that, because he didn't feel like he should have been opening for Patti, who was fast becoming his girlfriend. I think it's just another ego thing, probably, and I thought, "Well this is STUPID, because it'd be a great opportunity for us to get out and really get in front of some crowds and then maybe do something as a band, like get a record deal and make a whole album or two or three," or whatever.

So we just did the three dates, and they were GREAT dates; we were playing in front of big crowds with a real nice P.A., big stage and stuff, and Patti treated us really well, and we were friends with the band, and everything was going great, but then we stopped and went back to playing these crummy little clubs around Detroit, just whatever local gigs we could get, and it was like, "Why are we DOING this when we could be playing San Francisco opening for Patti?"

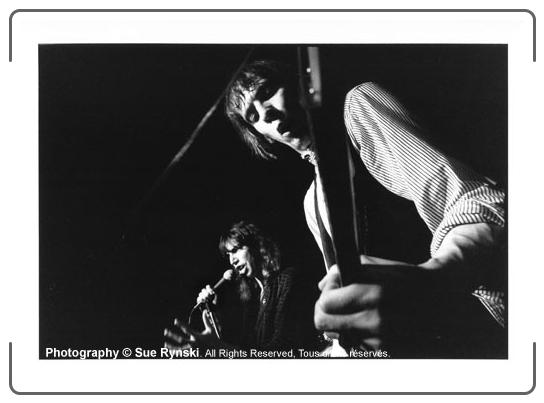

Patti and Sonic - Sue Rynski photo

GARY RASMUSSEN: And sometimes she would show up at our gigs. We'd play some odd place, playing Chicago or Milwaukee or something and Patti would be there. Patti would be backstage with us and we'd go out to play, and people would be watching us play, and then Patti would come out to watch us play, and everyone would stop watching us play and they'd go WATCH PATTI WATCH US PLAY! So that was kinda weird.

DENIZ TEK: [When I returned to Michigan in 1979, Patti] was around, and they were still playing some of these rural gigs, too, but when they would play in Ann Arbor, they'd play at the Second Chance, and when they would play in Detroit, they'd play at Bookie's, which was kind of a punk...by then, punk had sort of hit and that was a punk club. Destroy All Monsters [an arty Ann Arbor band that had added Ron Asheton and a now-free Michael Davis for rock credibility] played there a lot. But the Second Chance was really a good venue...a big club, and by then, Patti was always around.. I just remember her holding onto her clarinet at the side of stage, and she would occasionally get up and play clarinet. I'm not sure why, but I just remember her clutching that clarinet at the side of the stage and waiting to come up. But I never talked to her. She was really reclusive and didn't talk to me. Maybe she talked to other people and it was just me, but my impression was that she was reclusive and didn't talk to people.

When Patti was around, she would go to these gigs and just...seem real DIFFERENT to the people. You know, these big burly Michigan hunters and fisherman types, backwoods-type guys, or auto worker types would already have consumed a case of beer and they'd come over and try to get Patti to dance and things like that...she'd CRINGE. I never really heard her say anything to any of those guys; she'd just sort of give them this look and cringe and they'd just shrug their shoulders and walk away.

I think she'd probably consider ME a hick, too, because she wouldn't really talk to me, either. When she was around, I was just this guy who would show up with my guitar because Fred would invite me to come down and just play on the song "City Slang" - that was all I did; I didn't sit in for the whole set or anything, it was just for that song, which would usually be the encore. He just liked to have extra guitars on that song, and knew I could play it, and he was a friend of mine, so he'd invite me down. I think I was told by one of the band guys, I don't remember who, that there were 12 guitar tracks on that. There were 12 guitars on that, and the more guitars the better, as far as Fred was concerned.

[Between 1976 and 1979, the band was] not much different. They had some new songs, and more of it was original. They played more originals and...actually, I was going to say better sound, but I never heard them have bad sound anywhere. They were always able to balance their sound real well. Toward the end, they had the "City Slang" single. That was their big finale. But the band itself, I don't think they changed fundamentally. Just bigger crowds. More people. When you're playing to a huge crowd, people are going nuts, it always pushes you a little bit further, and maybe some of the performances were more over the top, a little wilder. They were more laid back in the early days, because they were playing to 20 or 30 people, 40 people in a redneck bar. They were still great, though!

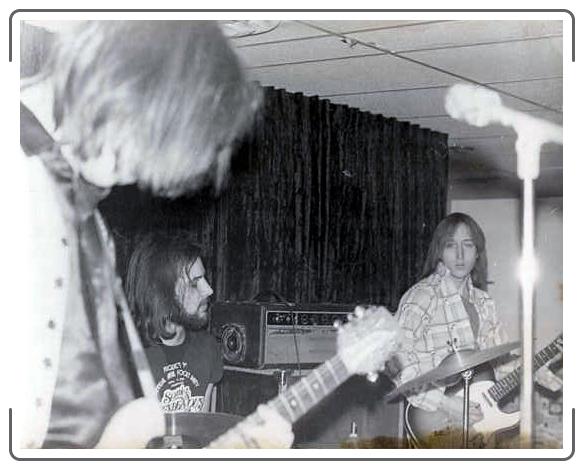

Gary and Scott. Sue Rynski photo

NEXT YEAR IN ISHPEMING AT THE SPORTSMAN'S BAR

SCOTT MORGAN: My relationship with Fred ultimately proved to be our undoing, I think, because it became, instead of a partnership, more like a competition. Maybe that's not the right word, but it became dysfunctional in its own way. Not in a REALLY bad way, but just enough that it became like an unhealthy dynamic. I got to the point where I wasn't singing much anymore, my songs were being VETOED and stuff like that, and I just felt like it was time to move.